Years of increasingly stern sanctions are taking a serious toll on the Iranian economy. Though the Islamic Republic of Iran has long been at odds with the United States and the West with regards to its nuclear program, this summer has seen the imposition of the toughest sanctions to date. In July of this year, the European Union placed a total embargo on oil imports coming from Iran, which only last year was their 6th largest supplier of crude oil. Meanwhile the United States recently passed a law subjecting any foreign country buying Iranian oil could be subject to punishment.

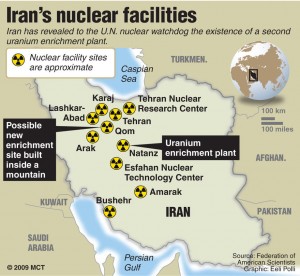

There is no doubt that these punitive measures are negatively impacting the Iranian economy: the current value of its currency, the Rial, is less than half of what it was last year, while oil exports have dropped by almost 30%. The United States and its allies believe that eventually the negative repercussions of sanctions will prove too much for the Islamic Republic to handle, forcing it to acquiesce to US demands by halting its uranium-enrichment program and dismantling its nuclear plants.

Economic sanctions—a form of coercive diplomacy—have long been a favoured tool for states wishing to exact a behavioural change from their adversaries. The use of sanctions has persisted and has in fact risen over the past several decades despite an overwhelming consensus amongst academics and policy makers that sanctions rarely work in achieving their stated goals. If that is indeed the case, then why are sanctions so commonly used? Sanctions are often viewed as a type of ‘middle ground’ action, as they offer a way of exerting influence that is potentially more effective than basic diplomatic efforts, but also do not involve the extensive resources and casualties associated with military action.

The Human Cost of Sanctions

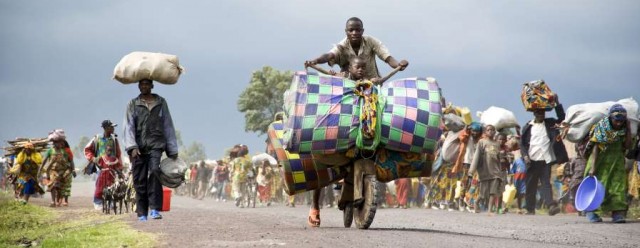

Despite being viewed as a low-impact form of statecraft, the human costs associated with sanctions are high, and the victims are rarely the intended targets. In most cases, civilians bear the brunt of suffering when sanctions are imposed on their state. Iran is no exception. With the price of food and basic consumer goods skyrocketing and unemployment continually rising, it is the average Iranian who is paying the price for its regime’s refusal to meet Western demands. When sanctions target civilians rather than state leaders, the assumption is that eventually the population will pressure their government to cooperate with the sanctioning state’s demands. This is a risky strategy and may wind up with the opposite desired outcome: by making the business environment unsuitable for private firms, the state becomes the only entity able to step in and alleviate the suffering felt by the population. In this situation, the state becomes the saviour rather than the enemy. Perhaps this strategy may work in a functioning democracy, but hardly applies to the case of Iran. In 2009, when thousands of Iranians took to the streets to protest the re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, they were met with brutal repression. There is little reason to believe that protesters this time around would be met with any other fate.

So far, increasing the severity of sanctions has not compelled Iran to cooperate at the negotiating table. The hope is that continuing the sanctions regime will eventually cause Iran to reach its breaking point. But there is also the risk that persistent sanctions which offer no initiatives for cooperation could lead Iran to believe the US is after regime change. Once this conclusion is reached, it will be unlikely that any level of sanctions will persuade the Iranian leadership to heed to US demands.

Why Sanction?

What can explain the persistent use of a foreign policy tool that is widely perceived as not only ineffective but often counter-productive? In the case of Iran, there is a significant amount of pressure on the American president to simply ‘do something.’ A large amount of this pressure comes from Congress, which itself feels the pressure from lobby groups and its domestic constituencies. The timing of many of this year’s new sanctions is key; as the presidential election draws nearer, the need for Obama to ‘appear tough’ on Iran is crucial.

Pressure from Israel, the United State’s key ally in the region, is a key part of the picture. Israel—currently the only nuclear power in the Middle East—has made it very clear that they will not accept a nuclear-armed Iran, fearing it would be a threat to its very existence as a nation. Although there has long been speculation about the possibility of an Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities, the situation is reaching a breaking point. In recent months, a number of top US officials have visited Israel in an effort to convince the leadership that increasingly crippling sanctions will force Iran to abandon its nuclear program and that an Israeli strike is not necessary. Military officials in both countries continue to warn that a strike on Iran would be disastrous, as it would be very difficult for a unilateral Israeli strike to destroy Iran’s nuclear capabilities. Although it is arguablethat the threat has been overblown, key players in the Israeli leadership—Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Ehud Barak—seem to be gearing up for the possibility of a strike in the near future.

Now What?

The United States is in a tough position. Sanctions aren’t working, yet a military strike on Iran must be avoided at all costs. Doing so would only encourage Iran to develop its weapons further, involve the US in another deadly conflict in the region and may end up strengthening civilian support for the regime. The real answer may be an honest effort at diplomacy and focusing on empowering the Iranian middle class rather than alienating it. If there is going to be a meaningful avenue for change in Iran, it is going to be the middle class and not a foreign power. Unfortunately, the US is now so deep into the sanctions regime that it could hardly pull out even if it wanted to—to do so would appear weak and seriously reduce the credibility of any threat it makes in the future. It would also increase the likelihood of an Israeli strike on Iran. Instead, the focus may need to rest on working with Israel to prevent a military confrontation in the short run, and slowly returning to a diplomatic solution in the long run. Let Iran be a lesson for the future—sanctions don’t work, and need to stop being a crutch for policy makers to rest on.