In April 2015, a video surfaced of an independent group of 45 women armed with AK47s near a church in Northern Syria. While this seemingly autonomous group lacked any vocalized connection to an official terrorist organization, their mission was clear: to insist that a woman’s role in the state and military should be equal to that of men. These women denounced extremist groups, specifically ISIL, who confine women within their organizations to the domestic household, as mothers and homemakers.

Although these women’s goals are well defined, their group’s identity is ambiguous. Most media outlets call them jihadists, simply because there is no other appropriate terminology to label such a new phenomenon.

While jihad may have been a cause that drove these women to action, it’s crucial to distinguish their definition of jihad from the one used by ISIL. Some posit that jihad refers to the use of religious extremism to accomplish a political agenda. However, there is an important caveat that needs to be drawn: the definition of jihad manipulated by extremist groups does not advocate the tenets of Islam as traditionally interpreted from the Qur’an, but one that rejects change and innovation and serves to rid the world of all that does not comply with their narrow perspective of what God’s teachings are, and the role of the Prophet.

In a January 2015 report by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a female recruit is referred to as muhajirat, which translates to female migrant. This distinction of terminology reflects the discrepancy between what a woman’s role is perceived to be versus the reality. Now, the question to ask is whether this new female jihadism is a reaction to ISIL, or a reaction to the West.

These actions are geared towards terrorist groups, sending a message to the female members of ISIL; that their role should go beyond the confines of the household, and combatting the traditional perception of women within extremist groups. ISIL in particular has expressed within their publications that women should be restrained to motherhood, leaving frontline combat to men.

This protest occurred months after ISIL disseminated a document entitled Women in the Islamic State: Manifesto and Case Study. The text details a semi-official account of how ISIL expects women to behave. It specifies, “The fundamental function for women is in the house with her husband and children.” The narrow role of women defined in the document directly conflicts many of ISIL’s online recruiters, which exaggerate women’s roles within the organization and thus obscuring the extent to which gender discrimination occurs. This protest was a symbol that women can, and perhaps should, take an active role in the military to protect their country. It presents a new perspective on the role women want to have in these predominantly extremist states. The limited accessibility to engagement within the organization reflects the additional constraints placed on women.

Another audience that these women’s actions could have an impact on are female foreign fighters seeking to join ISIL. Scholars have attributed various explanations for the reasons that women participate in jihadist movements. Such reactions have distilled to a three-pronged response (1) combatting social and political inequalities such as gendered oppression; (2) economic incentives such as providing a sustainable income for family; and (3) visions of martyrdom where these women could leave a lasting legacy of heroism within their communities.

It’s essential to dispel these myths. Media geared towards Western recruitment glamorize life as a woman in ISIL, shown with guns and positions of power, when in reality there’s little opportunity for upward mobility.

With new Jihadist women entering the foray, there’s a need to consider the implications they have for perceptions of women around the world. More women must follow suit by taking action to signal the severity, urgency, and legitimacy of their mission. The media must take an active role in highlighting these women as an interest group that sheds light on the harsh realities of women within terrorist groups, and how their efforts to deconstruct gendered barriers are being perceived by extremist groups.

Symbolically, these women represent an important change that has yet to be vocalized before – the desire of women to defend their state without the traditional patriarchal constraints of extremist groups.

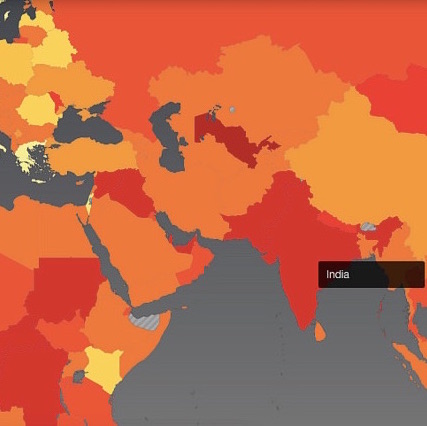

Image courtesy of Kurdish Struggle of a Kurdish YPG Fighter.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.