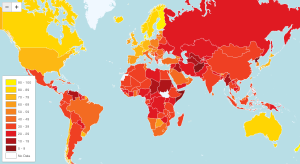

Transparency International recently released its annual Corruption Perception Index (CPI), a color-coded map of the world that depicts least-corrupt nations in yellow and most-corrupt nations in red. The organization defines corruption as “the misuse of public power for private benefit” and argues that the world is in desperate need of a “renewed effort to crack down on money laundering, clean up political finance, pursue the return of stolen assets and build more transparent public institutions”. Unsurprisingly, most of the CPI’s yellow countries happen to be rich Western countries, whereas countries of the global South are covered almost entirely in red. Among the CPI’s most highly-corrupt nations are Afghanistan, Somalia and South Sudan.

There is certainly a great deal of corruption in the global South. For example, in what is now South Sudan, corruption has been a well-known problem since 2004, when the state first gained control of the oil revenue within its territory. Despite its oil reserves, mineral deposits and vast stretches of farmland, corruption has rendered South Sudan one of the world’s poorest and least-developed nations, with a literacy rate of just 27% and frequent outbreaks of tribal conflict.

There are clear parallels that can be drawn between the CPI and the Canadian government’s perceptions of corruption in First Nations communities.

Following its release, critics immediately took to denouncing the CPI for glossing over the Western world’s contributions to many of the problems in the global South. Examples of corruption aside, the CPI and the broader mandate of Transparency International are particularly dangerous as they attempt to distract the public from the Western world’s role in contributing to the problems in the global South and to absolve the West of its responsibility to play a part in any solutions. Earlier this year, Transparency International launched a Twitter campaign entitled “#StopTheCorrupt”, which served as a rallying point around the CPI’s message of cracking down on corruption in the global South. This type of language is particularly dangerous for three main reasons: 1) it brands lesser-developed countries as no-good and corrupt, presenting a mere surface-level depiction of what are often extremely complex societies, 2) it perpetuates an “us and them” mentality and 3) it further distances the West from its involvement in contributing to the problems in the developing world in the first place.

There are clear parallels that can be drawn between the CPI and the Canadian government’s perceptions of corruption in First Nations communities. In 1876, the Indian Act was first enacted, introducing new measures such as the reserve system, Indian status and more – all aimed at allowing the Canadian federal government to control all aspects of Aboriginal life. In this arrangement, First Nations communities must overcome significant barriers in order to grow and prosper. As a result, addiction, suicide, hopelessness and money laundering among elected band officials affect many First Nations communities.

The rhetoric employed by the Canadian government has attempted to absolve the non-Aboriginal population of its obligation to take responsibility for its role in contributing to the problems in many First Nations communities. Last year, when asked about the dire socio-economic conditions in the First Nations community of Attawapiskat, Prime Minister Stephen Harper responded that the community had recently received $90 million in federal funding, perpetuating the false perception that the federal government simply hands out money to First Nations band councils – who then spend it all. Similarly, in 2012, Natural Resources Minister Joe Oliver called Aboriginal communities “socially dysfunctional”.

The language employed by both the Canadian government on the Aboriginal file and Transparency International in its Corruption Perceptions Index attempt to distract the public from the Western world’s direct involvement in contributing to the social, economic and political issues in developing nations. This language is particularly worrisome as it stands in the way of accepting responsibility for past injustices and ultimately working towards a more just relationship with these nations.