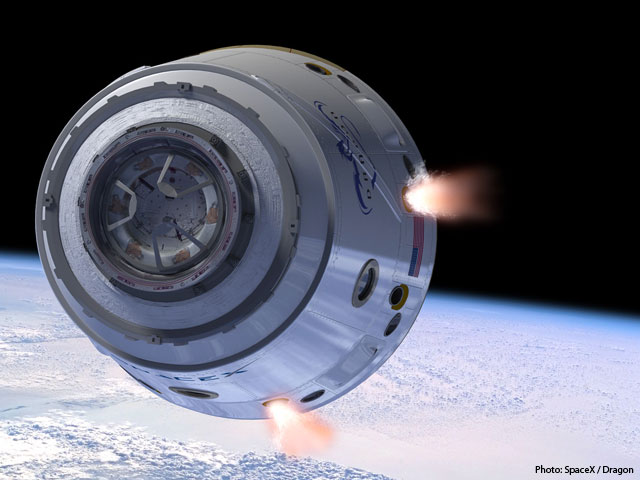

On September 16th, 2014 NASA announced the selection of two American companies, Boeing and SpaceX to be awarded contracts to enhance NASA’s Commercial Crew Transportation Capability. Boeing and SpaceX will develop and use the CST-100 and Crew Dragon spacecraft, respectively, with the end goal of sending astronauts in American-made spacecraft and thus ending NASA’s reliance on Russia to ferry astronauts to and from the International Space Station by 2017.

According to NASA administrators, contracts will be worth up to $6.8 billion USD, with $4.2 billion USD being awarded to Boeing and $2.6 billion USD being awarded to SpaceX. Contracts to both companies have the same requirements in order to be completed successfully. There must be at least one test flight per company, which will be administered in the presence of at least one U.S. astronaut aboard in order to verify the crafts ability to successfully launch, maneuver and dock at the Space Station. Once tests have been completed, both contractors will complete two to six missions to the International Space Station.

NASA’s decision to involve private industry in the task of advancing their Commercial Crew Transportation technologies will restore the capability of the U.S. to send American astronauts to space from U.S. soil for the first time since 2011. Private companies will own and operate the craft and be able to sell human space transportation to customers besides NASA in order to supplement costs, and it will allow NASA to turn its focus to future missions such as deep space travel to Mars.

In short, NASA is using private enterprise to reinvigorate the space race. This raises the question of what other implications arise from privatizing space travel. Boeing has been part of every American human space flight program and is an industry leader. At the same time the Boeing Company, Boeing Defense, Space and Security, is one of the worlds largest defense contractors and the single largest manufacturer of military aircraft. The partnership of Boeing and Lockheed, another international defense procurer, encompass the United Launch Alliance which developed the Atlas 5 rockets that were used to launch Boeing’s CST-100. The concession to the argument, then, for the involvement of private industry in the development of low-Earth orbit crafts is what other applications could there be for such a craft?

With the craft being privately owned and operated, NASA has no direct chain of command supervising the use of said technology. NASA itself recognized the ability for these contractors to sell space transportation services to others beside themselves, so who may that involve? What could this mean for future defense procurement contracts? There are of course no direct implications that any such ulterior uses for the CST-100 or Crew Dragon exist, but these are all things that need to be considered when private industry is involved with research and development on this scale.

Another issue to consider in the case of Boeing and SpaceX’s acquisition of these contracts is the timing of NASA’s decision to move away from supporting Russian space missions and seeking the help of the private industry. This then begs the question of whether this is a rushed move in order to distance America from supporting Russian defense contractors, or if this a long-time, planned move away from government organizations towards privatization?