On June 2, 2016, OPEC members gathered for their 169th Summit in Vienna, with the goal of setting a new collective ceiling. After the failure of their previous Doha meeting in April, many hoped they would finally come to an agreement on a clear oil output strategy. With oil trading at a six-month high, OPEC members aimed to demonstrate the relevance of the splintered organization, yet, once again, the meeting ended without resolution. The current policy of essentially unlimited production has resulted in price crashes, which OPEC looked to stabilize through freezes and lower oil supplies. That OPEC could not agree on a benign deal is a sign that political differences are undermining the organization and questions of its future in today’s market continue to be raised.

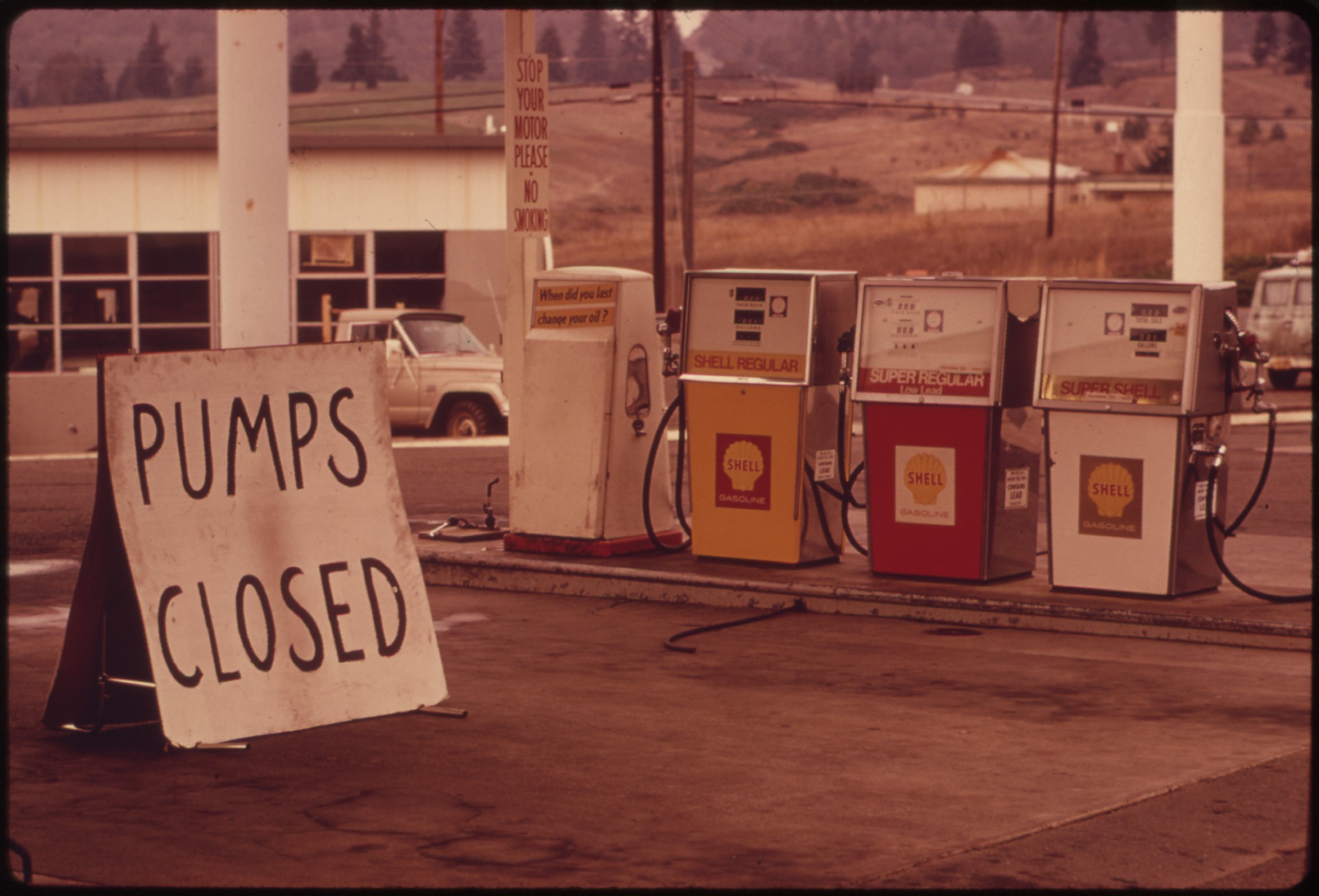

In 2014, Saudi Arabia and its Gulf Arab allies decided to abandon production constraints in favour of a market-share strategy. Saudi Arabia flooded the market in order to put new, and old, competitors (U.S. shale producers and Iran) out of business. When oil prices are low, the biggest winners will be Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, where pumping costs are much lower. In this strategy, they left other OPEC members to fend for themselves as oil prices spiraled downwards. At its previous meeting in December 2015, OPEC effectively allowed its 13 members to pump at will. As a result, prices crashed to $27 per barrel in January – their lowest in over a decade.

The price of oil has slowly crept back up to $50 per barrel, and Arab states wanted to stabilize all members’ production at around recent levels. However, geopolitical tensions hindered any co-operation in the deal. Iran took a firm stand against any move that would limit its own production, as it aims for an economic comeback following the end of Western sanctions in January. “I don’t agree with an overall output ceiling for OPEC,” Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Namdar Zanganeh said Thursday before a meeting of the group. Iran insisted on steeply raising its own production, though Tehran’s arch-rival Saudi Arabia promised not to flood the market and sought to mend fences within the organization.

The failed meetings this past week seem to confirm the reality that the world’s most famous cartel, has never really been a cartel. Analysts have declared OPEC a dysfunctional organization which has outlived its usefulness. There is lack of solidarity with the strongest members showing little interest in propping up the oil price to bail out the weak or failing members, Venezuela, Nigeria, Libya, Iraq and Algeria, dubbed the ‘Fragile Five’. Introducing a ceiling would show that “OPEC is still important to the oil market,” Gary Ross, chairman of PIRA Energy, a New York-based oil consultant, said. It would signal that “despite political differences, they can work together to achieve similar economic interests”.

While such a cap remains elusive, prices have risen anyway as the solution to low oil prices is, in part, low oil prices. Low prices cut supply by making production uneconomic for higher-costs producers, while also lowering investment in new fields, meaning prices rise. Members repeatedly stated that the market is rebalancing, and citing rising demand in the U.S., India and other major consumers as playing a major role in their decision. OPEC officials said in a news release that the market is “moving through the balancing process,” with prices having climbed by more than 80% since December. Therefore the members felt little pressure to take significant action to curb the world’s huge oversupply of crude, which is already decaling on its own for various reasons. While low prices prompted cuts in spending on global oil production in several countries, other OPEC member nations have been hit by economic and political crises, severely affecting their output. Nigeria, for example, has faced near daily attacks by armed militant groups, which have sent oil production plummeting. Venezuela, home to the world’s largest reserves, is on the verge of economic and social collapse. Libya’s oil production has suffered immensely during its five year long civil war, in which the Islamic State has now gained a foothold and attacked oil installations. The United States made strides towards energy independence, yet with crude oil priced at around $30 a barrel, hundreds of billions of dollars in US energy bonds are now viewed as “the new sub-prime”. Prices are still too low to encourage renewed interest in places like the deepwater, Arctic, or lesser shale plays. Yet while the disruptions to supply and lack of political stability may have sustained the recent rise in oil prices, they complicate forecasts for the future.

On the demand side, despite slowing global growth, the IEA remains confident that world oil consumption will keep rising this year, with a booming India almost out-pacing a slowing China. Despite the setback, Saudi Arabia moved to soothe market fears that failure to reach any deal would prompt them to raise production further to punish rivals and gain additional market share. The meeting’s outcome “reinforces the fact that control of the market has been handed to the market itself,” said Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of IHS and a top energy expert. He believes the “new normal” for crude will be $60-$65 per barrel, and the days of $90 and $100 per barrel are long gone. OPEC still accounts for 40 per cent of global oil production, yet Russia and The United States are two of the biggest oil producing countries. The organization is surely not finished, but in the face of deep divisions and rising competition, its ability to control the market and move prices up and down at will, is vastly diminished.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.