In 2011, when the “Arab Spring” protests advocating for the removal of long-time authoritarian regimes in North Africa hit Libya, a combination of corporate interests, realpolitik power calculations, and global humanitarian concerns led the West to intervene. For most of the decade that followed, Libya became a quintessential failed state. Resultantly, many in the West consider Libya another example of the West’s weakness and inability to intervene effectively in the Muslim World (eg. Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan), as well as a major roadblock in efforts at democratization. While Libya certainly has not democratized effectively at time of writing, there is much more nuance to this case than a discreditation of the idea of regime change.

NATO took up the R2P (Responsibility to Protect) doctrine as its justification for intervening in Libya. R2P is international law, officially recognized by the United Nations, which enshrines the principle that the international community has a responsibility to protect civilian populations from organized campaigns of violence and genocide when their own domestic government is either perpetrating these actions or is unable to stop them. R2P has become increasingly significant since the end of the 20th century, as wars have become asymmetrical, that is, less likely to be restricted to conventional battles, but rather involve heavy civilian collateral damage. NATO defines enforcing R2P as a fundamental part of its mandate. There are three benchmarks NATO has created for R2P missions: mitigating harm, supporting humanitarian needs and services, and creating a “safe and secure environment” for civilian populations.

These benchmarks quickly became relevant in Libya when Gaddafi’s government began its military rampage against civilian populations who opposed him in 2011. His government took power in 1969 through a coup when Gaddafi was a 27-year-old colonel. Once in power, Gaddafi expelled foreign soldiers, welcomed PLO fighters and other guerrillas, and seized and nationalized foreign banks and oil companies. Many of the guerrillas and terrorist groups based in Libya carried out attacks in the West such as a 1986 bombing at a discotheque in West Berlin and the bombing of Pan Am flight 103 over Lockerbie in Scotland in 1988. This embroiled Gaddafi’s government in frequent international boycotts and resulted in occasional foreign military action, for example a bombing of Gaddafi’s palace carried out by the Americans in 1986. When the “Arab Spring” reached Libya, Gaddafi mobilized his army with the declared mission of the violent eradication of protests, which he detailed in this chilling speech. Both eyewitness and journalistic accounts indicated that Gaddafi’s forces had begun this threatened eradication and would continue this destructive course. By March, France and the UK had advocated for a NATO military intervention to stop him, ultimately gaining the support of the USA. In October 2011, the overthrow of Gaddafi had been completed with his capture, torture, and execution by rebel forces.

When intervening in Libya, NATO’s stated interests were very clear: imposing the UN Security Council resolution calling for an immediate ceasefire in order to protect civilian life. At the same time, NATO’s own strategic interests aligned with this policy. However, there were very likely mixed motivations among individual NATO member states in their decisions to initiate and participate in operations against the Gaddafi regime. At the time, NATO did perceive a strategic interest in guaranteeing energy supplies for its members. It is unlikely that Gaddafi’s control of oil resources critical to Allied energy security played no role in NATO’s decision to intervene against him. However, NATO military options do need to be approved by the entirety of its members, which included many with no oil interest in Libya.

There was no orderly transition to a post-Gaddafi regime. Instead, Libya suffered a civil war in 2011 and again from 2014 to 2020. As a result, there was a complete failure to establish any governing institutions capable of delivering security, basic health and education services. The financial and oil sectors operated independently of the government, handing out money to rival militia leaders in a quasi-mafia clientelist system. As of 2016, the UN considered approximately 1.3 million Libyans, from a population of 6.2 million, to be in need of humanitarian assistance. Since 2014, nearly 30,000 Libyans have died trying to cross the Mediterranean. To end this chaos, a cease-fire between the different militias was signed in 2020. It has held to date, though somewhat tenuously.

A primary aim of the cease-fire was to allow for the installment of a national governing entity. The first attempt at such a structure following the removal of Gaddafi was the NTC (National Transitional Council), made up of former Gaddafi-era officials who had defected from his government and exiled intellectuals. This group presented itself as the government-in-waiting during the protests and quickly gained Western support during the NATO intervention. However, they were never able to establish governance outside of Benghazi. In 2012, following more protests and elections, this became first the GNC (General National Congress) then the GNA (Government of National Accord), backed by the United States and Türkiye. Both the GNC and GNA tried to govern the entire nation from Tripoli. Currently, a rival militia governs in the east and is supported by Egypt, the Arabian Gulf, and France. Corruption, state incapacity, and outbreaks of violence have remained the norm throughout this difficult process.

This tragic case raises obvious questions: What caused the failure in Libya? How can such failures be avoided in the future? In an analysis for Brookings, Washington Post columnist Shadi Hamid convincingly argues the failure was not in NATO’s R2P-driven mission to remove Gaddafi, but rather in the Obama Administration’s after-plan. NATO successfully prevented Gaddafi from perpetrating the kinds of massacres that Assad unleashed in Syria. Hamid defines the failure in Libya as a subsequent failure of democratization. The post-Gaddafi plan depended very heavily on the TNC’s ability to govern without significant American military involvement. This clearly did not happen. Therefore, one must ask if this plan was more the result of strategic calculations about Libyan or American domestic politics. At home, Obama had campaigned against American involvement in the Middle East and was facing another election campaign (2012) with a domestic mood hostile to such involvement. Given that the United States trying to fill the predictable power vacuum in Libya was not possible, plans for a more comprehensive and shared foreign responsibility there may have supported a more effective transition.

Libya’s recent history, and the role of NATO actions in it, illustrates several important lessons. First, the world is inarguably better off with fewer tyrants backed by the Russian-Chinese axis, which denies basic economic and human rights to its subject populations and empowers terrorist groups like the Taliban and Hamas. Preventing massacres of civilian populations is another inarguably positive achievement. Had the West, and particularly the USA, invested the necessary resources and military force to enable the TNC/GNA government to function effectively and independently after the removal of Gaddafi, Libya may well have avoided its decade of chaos. The fact of this failure should be a lesson to Western policymakers about moral clarity. Specifically, when analyzing causes of failed military interventions, policymakers and analysts must understand that one of their main causes is that enemies embed themselves in civilian populations. Insurgents hope that this will both paralyze the West’s ability or willingness to respond to them, and leave them well positioned to resume fighting and ultimately capture governance once the West backs out. The Taliban’s successful re-capture of Afghanistan is a striking example of this. This fact supports the claim that foreign powers who effectively subdue an enemy army must devote the effort, through both social and military means, in order to sustain victories for progress.

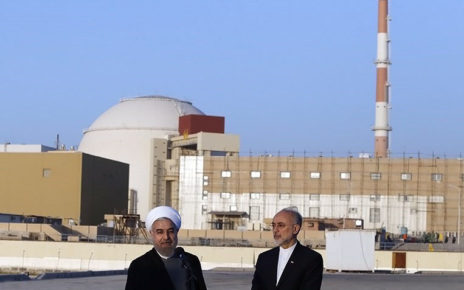

Photo: remnants of armaments from the Libyan post-revolution civil war. (2014). By UN Development Program via Flickr. Licensed under CC 2.0

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.