Soon after the death of Vladimir Lenin in 1924, the political rift that had steadily widened in the Soviet elite bared itself in the form of a fundamental ideological dispute. The conflict encompassed the entire upper echelon of the Bolshevik apparatus. On one side were Trotsky and his Left Opposition allies who advocated a policy of ‘permanent revolution’ as the key to the success of the world communist revolution. Opposing Trotsky was Stalin, who argued that since communist revolutions in industrialized countries, especially Germany, had already failed, it was necessary for the Soviet Union to focus on building its own strength. This necessitated the withdrawal or suspension of aid to communist movements around the world. Though Stalin eventually won out, the strife revealed the underlying disunity of the worldwide communist movement.

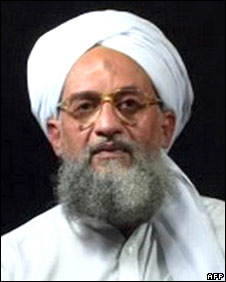

Today, a similar ideological conflict may be appearing in another revisionist ideology: militant Islam. Though Al-Qaeda is a shadow of its former self, it continues to represent the branch of militant Islam that appears to be the most prevalent — and the most dangerous. The breakdown in Al-Qaeda’s central leadership, first under Osama bin Laden and now under Ayman al-Zawahiri, has allowed for the creation of “franchises” that function relatively autonomously all throughout the Muslim world. Each Al-Qaeda affiliate struggles against Western or government forces in its respective region. Despite this, Al-Qaeda maintains, at least nominally, a pan-Islamic call to jihad, with the final objective of a unified Caliphate. Al-Qaeda has never attempted to form a single nation base, remaining a stateless entity.

Al-Qaeda, despite its many successes and its persistent status as the international face of jihad for the past twenty years, is far from what it used to be. Its leadership is underground, is systematically hunted, and exercises little authority over Al-Qaeda’s franchises. What has arisen to fill the practical and ideological gap left by the collapse of Al-Qaeda’s central leadership is the form of centralized, geographically limited militant Islam practiced by the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham (ISIS), now often simply called Islamic State (IS).

In its earliest forms, ISIS was a relatively unknown militia primarily active in Iraq after the 2003 invasion. Its fortunes rose and fell largely in relation to the overall situation during the American occupation. It was only with the breakout of the Syrian Civil War that ISIS took on its contemporary form, as well as its most commonly used name.

The differences in the overarching ideology of ISIS and Al-Qaeda, as between Trotsky and Stalin, are minute. The end is the same — a unified Caliphate— yet the means are very different. While Al-Qaeda envisioned the complete collapse of Western democracies due to overextension in Muslim states, ISIS has shown its willingness to limit itself geographically, at least initially, to build a centralized power base. It is far less focused on Western powers than Al-Qaeda.

By gaining a power base in Syria, ISIS was able to grow in strength by concentrating its efforts in a single area. Though it fought with both the government and other rebel groups, ISIS soon became a powerful player in the Assad opposition. With the resources of its captured territory in hand, it was able to launch an invasion of Iraq, capturing significant territory. With territory straddling the Syrian-Iraqi border, ISIS declared the establishment of a caliphate, and demanded the allegiance of all Muslims.

ISIS has therefore attempted to achieve the same goal as Al-Qaeda, through very different means. The declaration of a caliphate signals the Islamic State’s intention to continue its expansion, starting with its traditional claims in Syria and Iraq.

Although nationalist-Islamist movements are not uncommon, they have rarely met with the same success as ISIS. Should the group continue to survive, and gain greater territory, it may supplant the fading Al-Qaeda as the leader of the global jihad movement. With its centralized structure, it may prove more successful in gradually expanding its influence. ISIS seeks to form its Caliphate in much the same way the empire it idolizes was born, through rapid military expansion.

Despite the success of ISIS on the ground, the Syrian-Iraqi group may need to engineer a doctrine, on a theoretical level, more successful than that of Al-Qaeda. Though ISIS has succeeded in forming a relatively stable basis of support, the hardline jihadist ideology pioneered by Al-Qaeda and perpetuated by ISIS finds little support outside of the Islamic world. It has not proven itself a competent challenger to the dominance of liberal democracy or the nascent world view of market authoritarianism. This is yet another reason why the split in militant Islam more closely resembles the Trotskyite-Stalinist dispute than, say, the ideological conflict between communism and capitalism.

The complex relationship between these two foremost jihadist groups will undoubtedly be significant for the future of jihad as an ideological movement. ISIS has been closely linked with Al-Qaeda for most of its history, even acting as the Al-Qaeda franchise in Iraq for much of that time. With the resurgence of militant groups in Iraq due to America’s withdrawal and the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War, Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI, the groups original name) initiated a confusing, and eventually unconfirmed merger with the Al-Nusra Front, a Syrian jihadist group, to form ISIS. The botched merger exposed a rift between ISIS under Al-Baghdadi and Al-Qaeda’s nominal central leadership under Zawahiri, the latter of whom “ruled against” the merger. The two groups officially severed ties in February 2014. The division marked a significant defeat for Al-Qaeda, unable as it was to assert its control over one of its franchises.

The split between these two major jihadist groups represents both a practical and theoretical division within the global movement of militant Islam. Both Al-Qaeda and ISIS have worked, and continue to work, towards the goal of a global caliphate, but both face enormous hurdles. It seems that ISIS has found some success in focusing itself in a way Al-Qaeda never did, though the creation of its caliphate will undoubtedly create even further issues. It is unlikely that jihadist groups outside of Syria and Iraq will bow to Al-Baghdadi as Caliph, given ISIS’ past conflict with Al-Nusra and Al-Qaeda. Furthermore, as ISIS grows in strength, it will undoubtedly attract the attention of anti-jihadist forces. Just this week, the United States launched its first airstrikes against ISIS in Iraq.

It is unclear whether ISIS will be able to sustain its theoretical and practical momentum over the next months or years. Though they have a strong base of support straddling the Iraq-Syria border, they face challenges not just from the governments of those countries, and Western powers, but also from Kurdish groups, Shiite militias and even other Sunni rebels.