Nowadays, wireless communication plays an integral role in any average person’s societal interactions. On April 23, 2014, Pakistan issued its very first 3G and 4G network licenses to mobile companies. Initially intended to benefit urban areas, this opening of Pakistani markets to new technological developments will hopefully expand into rural regions as mounting economic benefits are reaped.

The introduction of 3G/4G networks in Pakistan will not only facilitate the online transmission of information, but might also draw additional attention to the government’s omnipresent bans on websites such as YouTube. In an attempt to minimize this renewed consciousness of online censorship, the Supreme Court of Pakistan decided to lift the YouTube ban before the 3G/4G network launch. Only certain videos or user channels, deemed inappropriate or obscene by the Pakistani government, are to remain beyond reach. Despite the latter restrictions, this ruling marks an important step in Pakistan’s progressive fight for media and information freedom.

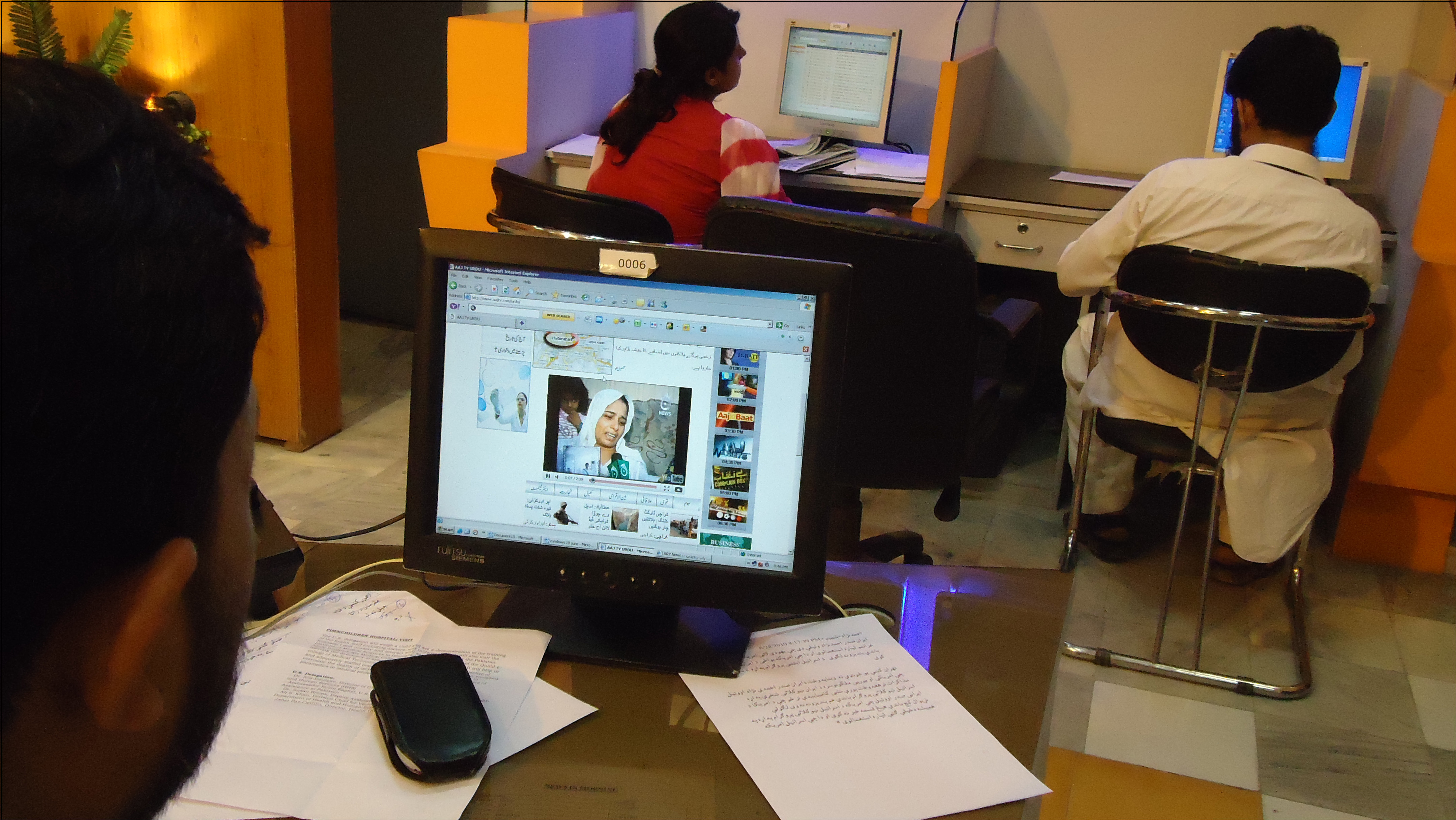

As wireless communication becomes increasingly available on newer and faster platforms, people’s interactions with their society, culture and even one another start to change. The implementation of the long overdue 3G/4G networks was met with unprecedented criticism by internet users. How practical was an increased bandwidth speed next to the Superior High Court’s liberal use of its power to ban websites considered anti-State or anti-Islam? The latter bans were even to be extended to search engines such as Google and Yahoo. However, the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) soon reacted to the other, dangerous repercussions of banning such search engines for sectors of the government. The Supreme Court, it was later revealed, would instead merely block certain words from being searched.

Such heavy, systematic censorship, despite the recent and somewhat promising YouTube ban lift, has had serious, permanent repercussions on Pakistan’s level of interest and investment in internet technology.

This aforementioned heavy censorship trend began four years ago, on May 19, 2010, when the Supreme Court approved of a ban on a Facebook page containing different drawings of Mohammad (the Islamic faith considers depictions of the holy prophet to be sacrilegious). A mere 24 hours later, over 450 website pages were banned for similar reasons. The majority of these pages belonged to popular platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, Flickr or Wikipedia, causing overall internet traffic in the country to drop by 25%. Although the government has yet to publish an official list of these online bans, an incomplete list was compiled by the journalist web site ProPakistani in 2010, and updated in 2012.

Such heavy, systematic censorship, despite the recent and somewhat promising YouTube ban lift, has had serious, permanent repercussions on Pakistan’s level of interest and investment in internet technology. The latter economic pitfalls became serious points of discussion as the government considered issuing the 3G/4G network licenses.

For instance, many government representatives were worried by the lack of competition apparent during its April 23 Spectrum Auction. The latter failed to attract any candidacies from mobile companies aside from those already entrenched in Pakistan. Some wonder if Pakistan should have followed Afghnistan’s suit, abandoning the auction and working towards brokering individual mobile company license deals instead.

So high was the level of public concern prior to the auction that Dr. Syed Ismail Shah, chairman of the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority, had to issue a calming statement during his meeting with the CEO of Waird Mobile Company.The statement promised that the auction itself would dispel all previous impressions of bidders’ lack of interest in the 3G/4G spectrum.

Another common concern raised was the affordability of 3G services, let alone 4G services, for the average cellphone user in Pakistan. Mobile companies have just spent millions of dollars on wireless broadband spectrums, expecting to cater to over 130 million individuals. Should these expectations prove faulty and a much smaller market be unveiled, these technological investments would amount to an irreparable loss of profit for all major mobile network suppliers in the country. Such a financial loss would likely lead to an ironic decrease in the quality and stability of mobile networks in Pakistan. Such a failure scenario could also make Pakistan mobile companies hesitant to invest in future network projects.

On a more positive note, the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) did manage to raise the promised 1.1 billion US Dollars in Spectrum Auction sales. This will assist the country in its bid to become a powerful player in the global economy by covering its costs as it works to develop a stable platform for its business development.

Despite its being the last country in South Asia to acquire 3G mobile internet, Pakistan’s recent actions have set it up for slow but hopeful growth. The network expansion will ultimately depend on mobile users’ switching to smart phones, a consumer decision only 10% of the 132 million mobile users in Pakistan have made so far. However, given that countries with similar demographics in South Asia and Africa have, even in the worst scenarios, managed to marginally benefit from similar mobile upgrades, there is every possibility that Pakistan will come out on the side of success.