The famous 1904 patriotic song by Urdu poet Muhammad Iqbal begins: “Sare Jahan se Accha, Hindositan Hamara” [Better than the Entire World is our Hind]. Asked by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi how India looked from the cosmos, the first Indian in space Rakesh Sharma wondrously recited those same mythic lines. The sentiment expressed is one that abides and resounds in the hearts of India’s ‘nightingales’, those children of the motherland separated from the ‘garden abode’ of the subcontinent, but longing ever still for its homely embrace.

* * *

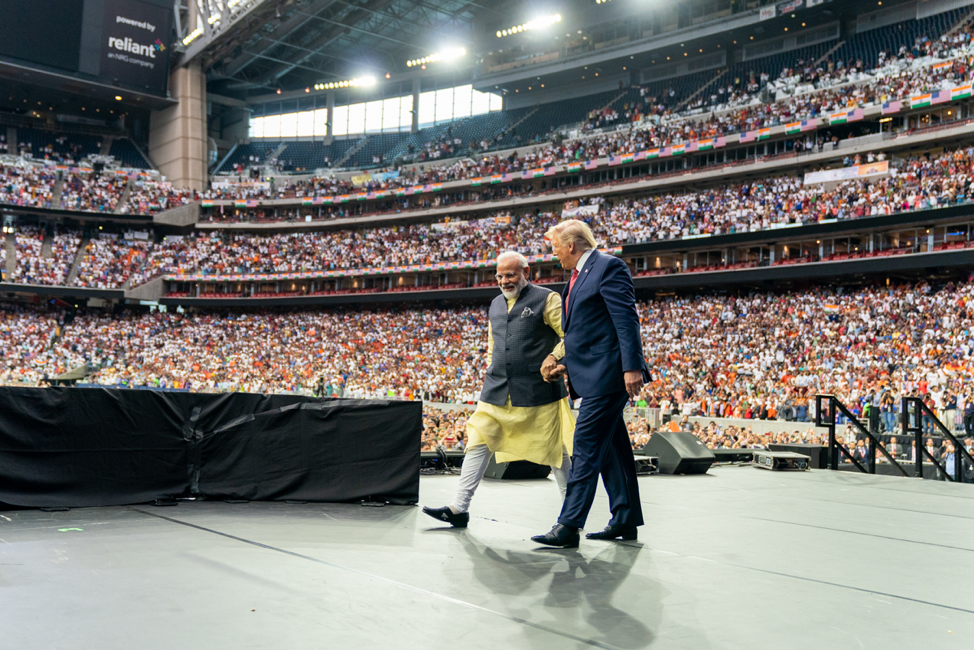

In September 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi joined President Trump on stage at the NRG Stadium in Houston, to the rapture and jubilation of 50,000 Indian-American supporters. The “Howdy Modi” event, in the vein of other mass musterings of the diaspora such as those at Wembley and Madison Square Gardens, came at a critical time for Indian diplomacy. With the UN General Assembly around the corner, Modi was preparing to face scrutiny over his government’s controversial Kashmir decision, and needed the United States to remain sedated in its response. The occasion marked a separate milestone as well: the political coming-of-age and growing organizational prowess of the Indian community in America.

India has the largest and most widely dispersed diaspora population in the world, numbering about 18 million. The United States itself is home to 4.4 million people of Indian descent, who now comprise 1.3% of the American population and are considered its “most successful immigrant group”. Recent Indian governments have begun to seriously consider the enormous financial and political heft of the diaspora, as evidenced by visits like the one in Houston. The new Minister of External Affairs, career-diplomat Dr. Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, has especially emphasized diaspora diplomacy as a key tenet of India’s global mandate.

Unlike many other histories of émigré movement and human flow, the Indian diaspora has largely not been a product of political upheaval or conflict. This has engendered a more fond and positive relationship between the Indian state and its expatriate population, a trust that Minister Jaishankar has called the “forte” and “unique aspect” of Indian foreign policy. The Ministry of External Affairs seeks a more direct engagement with this group, in keeping with India’s grander geopolitical ambitions; in a recent interview, he posits that major powers are particular about caring for their people, and that looking after the diaspora exists as a “fundamental foreign policy-strategic issue”.

In this regard, Jaishankar is building upon a foundation laid by his immediate predecessor, the late Sushma Swaraj. This includes the reintegration of the Department of Overseas Indian Affairs (created in 2004) back into the Ministry of External Affairs, in order to better service diasporic concerns. Minister Swaraj left a personal legacy of accessibility and care, with citizens in distress abroad often using her Twitter handle as a way to communicate their urgent needs.

Beyond the deep emotional connections binding the state and its disparate peoples, there exists a material component to India’s diaspora diplomacy. India is the world’s largest beneficiary of remittances from abroad, last year receiving $79 billion that directly fuelled foreign direct investment and domestic economic growth. When Indian lives are at stake, the military has not been hesitant to involve itself kinetically outside of its jurisdiction; in 2015, chaos in Yemen led to the evacuation of over 4,000 people by the Indian Armed Forces during Operation Raahat. In the Middle East and elsewhere, India has continually proven its commitment to defending its sizeable diaspora communities.

To the apparatus of Indian foreign

affairs, underfunded, underinstitutionalised, and understaffed, the diaspora

serves as a mechanism of ‘cheap’ diplomacy. As

successful immigrants who often integrate into their host societies,

whilst still retaining elements of their heritage, the Indian diaspora advances

the country’s public image abroad and operates as the ambassadors of ‘chutnification’: spreading Indian

culture, film, business, music, and food. There are real soft power advantages

to an active diaspora. This phenomenon can be demonstrated by the advocacy work being conducted by

Indian and Kashmiri groups in the United States, who on October 16th briefed

American congressional authorities on the history of terrorism and genocide in

Kashmir that have led to the concrete conditions of today.

Just as the Indian diaspora influences policy in their host countries, so too has this image reversed itself as the diaspora finds increasing relevance in the politics of the watan [homeland]. Every two years, the Government of India organizes the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas, a conference that looks to recognize the accomplishments of expatriates, and serves as an avenue for major policy announcements. In recent years, the wealth and clout of the diaspora has put them in a position to exert pressure on the Indian government on issues such as dual citizenship, the right to vote from outside India, and representation in Parliament. Modi has expertly utilized overseas Indians to influence domestic politics, and the BJP has found strong support amongst Non-Resident Indians [NRIs], many of whom returned to vote and campaign for the Prime Minister in this summer’s elections.

The diaspora has a long and romantic history within and outside India; they are at once more separate from and closer to their native soil than all others. It was Gandhi’s grassroots efforts and tactics as an attorney in South Africa that precipitated his prodigal return to the shores of Bombay, and informed his leadership of the Independence movement. It was V.S Naipaul’s post-colonial epics that shed light on the Indian community in the Caribbean, and brought Naipaul himself a Nobel Prize in Literature. India’s diaspora has always served as the living embodiment of its civilizational and philosophical imprint on the world, and will continue to do so as it forges a new and lasting strategic relationship with the country of its forebears.

* * *

غربت میں ہوں اگر ہم، رہتا ہے دل وطن میں

If we are in an alien place, the heart remains in the homeland

سمجھو وہیں ہمیں بھی دل ہو جہاں ہمارا

Know us to be only there where our heart is.

Featured Image: President Donald J. Trump joins India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi on stage Sunday, Sept. 22, 2019, at a rally in honor of Prime Minister Modi at NRG Stadium in Houston, Texas. (2019) by Official White House photographer Shealah Craighead via https://www.flickr.com/photos/whitehouse/48784282452/. Photo courtesy of The White House.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.