Budget 2017 did not exactly lack for words, but Finance Minister Bill Morneau has found yet another slogan for part of his fiscal plan. Describing the government’s position on international assistance in an interview with the Canadian Press, Morneau used terms that the budget could not: “Do more with less.” In literal terms, the comment is an exaggeration (the budget isn’t shrinking)—but it captures a deeper truth. In substance and in tone, Budget 2017 takes a very different approach to international affairs than its predecessor.

The whole language of the budget has changed. Budget 2016 contained an entire chapter on “Canada and the World,” and brimmed with promises to “rebuild our international influence” and “renew Canadian leadership”. This year, there is barely a reference to the world at all. The section on international affairs, a sub-chapter entitled “Upholding Canada’s Place in the World,” begins by saying: “In Canada, we have made the choice to build an economy that works for everyone.”

Clearly, priorities have been re-ordered. Whereas the current government’s first budget led with a discussion of international assistance, Budget 2017 devotes its opening pages to trade, the Canada-US relationship, and the plan to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

It is all part of a budget that seems to more closely link domestic interests with international ones. The focus is understandable: this budget, after all, was supposed to be about the middle class. Though the outlook for Canada’s economic growth is positive, new international assistance spending remains difficult to justify politically. Across the board, the government has clamped down on new spending to focus on following-through with allocations from the last budget.

Some of that follow-through will trickle into the international assistance budget. This fiscal year will see the government cover the final installment of a two-year increase to the international assistance envelope, which covers most of Canada’s Overseas Development Assistance (ODA). The budget also earmarked $650 million in reallocated spending on women’s reproductive health, upholding a longstanding promise to broaden maternal and child assistance to include sexual health.

What is lacking is a sense of direction for the future. The government spent much of 2016 conducting an International Assistance Review to develop a new foreign aid policy. The consultation process concluded in December 2016 and, as discussed here previously, was supposed to inform Budget 2017. That does not seem to have happened. Instead, the budget hinted at new programming priorities, including reproductive health and the Sustainable Development Goals, without going into detail.

Even the budget’s largest announcement—the news that Canada will create a Development Finance Institution (DFI)—wasn’t really news. The DFI and its initial capitalization of $300 million were announced in the previous government’s final budget, only to go dormant through 2016. Now that the plans are back on the table, they leave some questions to be answered.

New tools for development finance are meant to form part of the government’s wider innovation strategy. However, the strategy is missing. Canada’s DFI, like the ones that exist elsewhere in the G7, is intended to serve development by combing public startup funds with private investment. At the moment, it has no mandate, and the government has not indicated how development finance will fit into Export Development Canada (EDC), the crown corporation that is to host the DFI. Nor has the government explained how EDC, which normally serves the interests of Canadian businesses abroad, will work with the DFI to help alleviate poverty in other countries.

These questions are all the more pressing because development finance is an imperfect science. In Britain, where the highly-respected Department for International Development (DfID) is the best-funded in the G7, private development finance is controversial. Successive Conservative governments have maintained high levels of support for international assistance, but have increasingly channelled the funds to CDC Group, Britain’s version of the DFI. In the United Kingdom, as in Canada, international assistance is legally-mandated for poverty alleviation, but CDC Group has nonetheless found a way to spend money overseas on a range of luxury property developments, shopping centres, and gated community housing.

The Canadian government has been silent about these pitfalls. Instead, Budget 2017 (and Minister Morneau) have framed the discussion of international assistance largely in terms of innovation and efficiency-seeking. It is true that poverty relief efforts are strengthened by better tools, goal-setting, and modes of delivery, but funding levels also have an important part in aid effectiveness. Lack of resourcing has a cost—one that is paid in lives.

The Trudeau government has suggested that it sees international assistance spending as an important part of its governing ethos. New spending for maternal health jibes with the gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) that federal agencies are encouraged to use in making policy. Fresh commitments to the Global Fund match an assertion of support for multilateralism. Budget 2017 offered a muted affirmation of these goals, and some new tools to advance them. But sooner or later, you have to put your money where your GBA+ is.

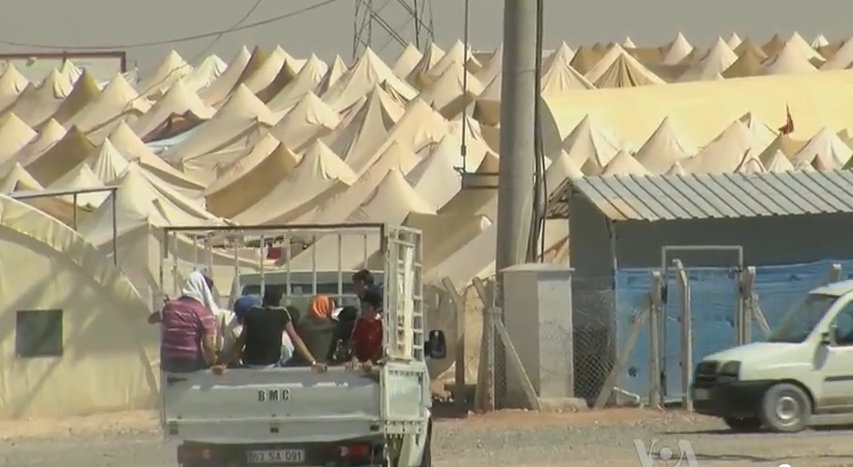

Photo: Canadian relief supplies in Penescola, Florida after Hurricane Katrina (September 11, 2005), by Jay C. Pugh via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under US Government Works.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.