In a grim example of historical reality’s capacity to outdo the reveries of the most fanciful fiction authors when it comes to conjuring irony, the conflict in Afghanistan ended as it began – with desperate people plunging hundreds of meters to their deaths, choosing one sordid fate in grotesque preference to an even more unspeakable one. Just as office workers in the World Trade Centre on 9/11 defenestrated themselves rather than burn alive, on August 15, 2021, desperate Afghans clung to the exterior of a US military transport aircraft that was hastily taking leave of Hamid Karzai International Airport and fell to their doom rather than experience Taliban “justice” for whatever crimes they expected the new regime to indict them with.

Disturbing parallels aside, the world of 2021 is radically different from the one of 2001. At the time Operation Enduring Freedom commenced, no one had ever heard of an iPhone, Wi-Fi was an esoteric concept, YouTube did not exist, and Rihanna was an unknown name. The Iraq War commenced, transpired, and ended, all comfortably within that timeframe. Since then, the Great Recession, the Arab Spring, the rise and fall of the ISIS Caliphate, and a global pandemic, not to mention scores of other singular historical events, have come to pass. To Generation Z, talk of a “War on Terror” today seems as anachronistic as a mountain-dwelling Taliban fighter in primitive dress Tweeting victory pictures from the Afghan presidential palace.

And yet, it is precisely this prodigious length of time – twenty years – during which the United States and NATO were committed in Afghanistan to the project of nation-building, and the colossal quantities of blood and treasure they spent in that enterprise, that makes the thunderclap abruptness of the Western-backed Kabul government’s demise so stomach-churning. One can only imagine the pain Allied veterans of the war in Afghanistan must be feeling at this very moment.

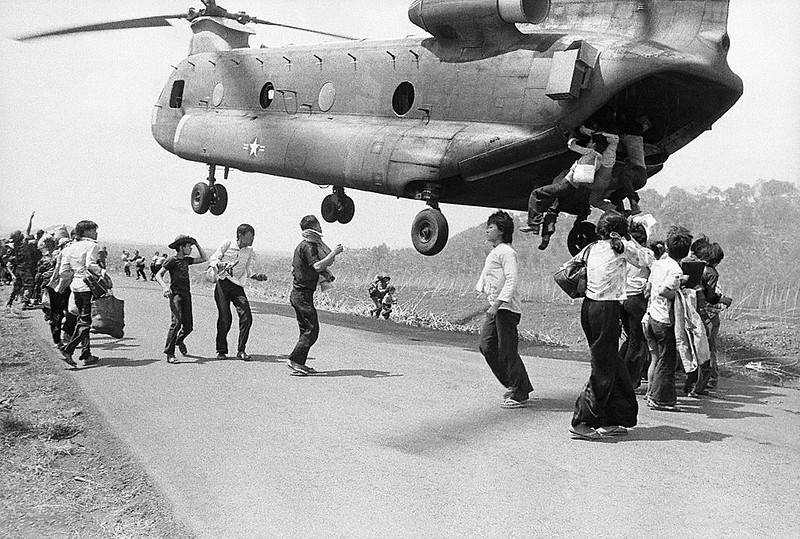

This kind of disappointment at a sunk cost is not entirely unprecedented, and it is helpful to turn to history in search of some perspective, perhaps even hope. The United States’ involvement in Vietnam began as early as 1945 with OSS operations designed, ironically, to help the Viet Minh (the forerunners to the Viet Cong) defeat the Japanese occupation. It only ended in 1975 with the fall of Saigon, forever immortalized in the pictures of the hurried rooftop helicopter evacuation of the US embassy as that city fell to the North Vietnamese Army. Commentators have not been able to resist pointing out the parallels between that instance and the frantic evacuation of the US embassy in Kabul in recent days. That thirty-year conflict in Southeast Asia and its apparent futility gave way to what observers labelled the US’s “Vietnam Syndrome,” a loss of confidence in world affairs that Washington found difficult to overcome. However, a mere fifteen years later, the United States and its allies all but won the Cold War without firing a shot and recovered a sense of destiny which manifested itself in some circles as lofty hopes for the “end of history” and a “new world order” – the universal expansion of the post-World War Two international order.

Barbarians at the Gates

Recent history should impress upon readers that, however grave the current hour may seem, a change of fortune is still possible through the combination of a providential turn of events and the determination of leaders not to lose heart. Now is not a time for despair, but rather sober reflection. When Rome was sacked in 410 AD, Augustine of Hippo responded by authoring The City of God in an attempt to ascribe a kind of cosmic meaning to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and to place it in intelligible perspective. The people of the Western democracies, of which NATO has become one of the salient transnational political expressions, need to apply themselves to similar ‘big picture’ strategic thinking. One should not press this analogy to the fall of Rome too far. The late Islamic Republic of Afghanistan was an incongruous outpost of the Western democratic sphere of influence. Kabul is not Rome. Its abandonment can be more fittingly compared to Rome’s withdrawal from Britain in the fifth century. The heartlands of the NATO states are not in any immediate danger. But Kabul’s collapse does suggest that the West is on the back foot. The frontier is moving closer, not emanating away. The prospect of the endangerment of the metropole of the Post-War Order no longer seems as remote as it once did. After all, in yet another twisted historical irony, literal horned barbarians have recently traipsed the marble floors of the neoclassical temples to the world’s most powerful and, arguably, indispensable democracy.

So, what is to be done? If the democratic world and, in particular, the states that comprise NATO have any hope of turning the historical tide and making the world safer for democracy and basic human rights, then the people of those states and their leaders need to think long and hard and concur on a basic self-narrative. They need to ask, “Who are we?”

It just so happens that the day before Taliban fighters seized the presidential palace in Kabul, dignitaries from NATO countries were meeting in Newfoundland to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Placentia Bay Conference between Winston Churchill, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and William Lyon Mackenzie King on August 14, 1941. This was a critical meeting of Allied leaders in which they spelled out and broadcasted their war aims against the Axis Powers – a vision for the establishment of a postwar order that centered on the proliferation of Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from fear, and freedom from want.

Allied leaders promulgated this “Atlantic Charter” at a bleak juncture in their fortunes. In August 1941, Germany appeared poised to conquer the Soviet Union, Britain and its empire stood alone militarily, and many further shocks, such as the attack on Pearl Harbour, still lay in the future. But the Atlantic Charter was precisely the moral standard around which the Allies needed to rally and sanctify their campaign. It proffered an idea worth fighting for. The salient first principle that can be palpably felt throughout the text of the Atlantic Charter was the Allied leaders’ ironclad confidence that the nations and peoples they represented were, to use colloquial language, “the good guys”. The greatest weapon in their arsenal was confidence in their moral authority. The Nazi regime made no pretence of honouring abstract universal moral precepts; it worshipped at the altar of “might makes right.” Despite the Allies’ production of awesome quantities of military materiel, it was the principles of the Atlantic Charter that gave them the mandate by which to harness and direct those resources.

Regrouping

The West needs a new ‘Atlantic Charter’ at this equally dark time. This charter must spell out the West’s self-narrative for the twenty-first century with all the focus and resolution of a laser. The first question this charter must answer is whether Western civilization still exists and, if it does, whether it is benevolent or malevolent, at least in the aggregate. In other words, are we still “the good guys”? This is a critical question. Unfortunately, it would be much more contentious in many Allied nations today than it was in 1941. Although the Washington Treaty establishing NATO in 1949 takes the existence of Western civilization, and its inherent goodness, as self-evident truths, solemnly affirming that in the preamble as its guiding first principles, generations of Westerners have since passed through an education system that has inundated them with the notion that Western civilization is either an amorphous ideational construct at best and a “Eurocentric” concept at worst. Other critics, taking its existence as a given, condemn Western civilization as a system characterized by a smorgasbord of intersectional oppressions, an entity in need of “deconstruction,” not preservation. As recent events highlight, these ideas are not currently serving the Western democracies well.

The loss of Afghanistan threatens to further demoralize NATO, its member states, and their constituencies. What is needed now is confidence and a renewed commitment to the values and institutions that triumphed in 1945, and again in 1991, and the inherent goodness of the societies that bequeathed that inheritance to an ever-expanding proportion of humanity. These are institutions and values that are currently under attack, often from within their own countries of origin. Much has been made of the low morale of Afghan troops, and many in the United States, Canada, and other NATO countries that invested so heavily in their training and equipment have expressed shock and dismay at the Afghans’ apparent unwillingness to fight for their flag. And yet, one wonders whether people in Western countries any longer have the credibility to look askance at such apparent apathy about the defence of sacred symbols and homelands. Many Canadians lowered their flags to half-mast in the wake of revelations about unmarked graves in Residential Schools. Many of them have kept them half-raised on a permanent basis or taken them down altogether. One wonders whether most Canadians would behave any differently than their erstwhile Afghan allies if asked to rally to the defence of their own flag and the country it represents.

Cover Photo: April 14, 1975, South Vietnamese refugees cling to an American helicopter during the fall of Saigon to the North Vietnamese Army. 05/03/2017. Picture by manhhai, via flickr. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.