In his first solo press conference on Thursday, U.S. President Donald Trump defended his position in developing a better relationship with Russia by arguing that the Obama administration did the same with its reset strategy. He then pivoted and took the chance to chide former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton by reiterating his earlier accusation of her handing over U.S. uranium to Russia.

This allegation against Clinton stemmed from her alleged link to the 2013 acquisition of Uranium One, a Canada-based uranium mining company, by Russian state-owned company Rosatom through its subsidiary AtomRedMetZoloto (ARMZ). Uranium One has assets in Kazakhstan and the U.S. and the transaction effectively granted Russian ownership to 20% of U.S. uranium production capacity – not uranium reserves as Trump is suggesting. However, did Clinton really give Russia access to U.S. uranium production?

The Clinton connection to Uranium One acquisition is due to Clinton and former U.S. President Bill Clinton’s affiliation with former owner Frank Giustra. Their relationship was first discussed in Peter Schweizer’s book Clinton Cash, which looked at foreign donations made to the Clinton Foundation. Guistra, who is an ardent supporter of the Foundation, reportedly enlisted the help of Mr. Clinton in order to secure uranium business dealings in Kazakhstan for his company UrAsia, which eventually merged with Uranium One in 2007. In April 2015, the New York Times’ Jo Becker and Mike McIntire worked on Schweizer’s data and conducted their own research. The resulting piece is a detailed account of the link between the Clintons and Uranium One executives. Based on a page from Trump’s website this article is his main source for the allegations.

Becker and McIntire discussed the possible conflict of interest that occurred. They reported that through the acquisition process from 2007 to 2012, individuals connected to Uranium One were donating huge amounts of money to the Clinton Foundation. This happened while Hillary Clinton was serving as the Secretary of State and her department was a member of the Committee on Foreign Investments (CFIUS), a panel tasked to review foreign investments for possible effects on national security. However, due to the confidential nature of the review process, it is not known if Clinton was involved at all. It was reported that former Assistant Secretary of State Jose W. Fernandez was the department’s representative in CFIUS and Clinton never concerned herself in the committee’s affairs. What is certain is that CFIUS has no power to halt a deal, only the capacity to move it up the chain to the President, who has the sole authority to decide to continue or stop it.

Underscoring the negative implications of his allegations against Clinton, Trump asked, “You know what uranium is, right? It’s this thing called nuclear weapons and other things. Like lots of things are done with uranium including some bad things.” Putting aside the Clinton factor, his statement on the face of it demonstrates inadequate understanding of the issue at hand and this is where Americans should be worried. Equating uranium to nuclear weapons and “bad things”, which he failed to clearly identify as to what exactly, does not increase confidence in his domestic and foreign policymaking with regards to the U.S. nuclear energy sector. Generally the U.S. relies heavily on foreign uranium to keep its power plants running. This is because while it is the largest producer of nuclear power internationally, it only has 1% of the world’s known recoverable uranium. In addition, its 2016 uranium production is at its lowest since 2005. In reality, the 20% U.S. uranium capacity is very little compared to the vast uranium assets Russia has and is planning to acquire.

Uranium One mining operations in Kazakhstan were the resources Russia was eyeing when it purchased the company. It was reported that ARMZ’s mandate was to boost the Russian supply of uranium because the country’s output was declining amidst the increasing demand. There were supply contracts to fulfill and there was also a plan to expand its nuclear energy sector by building 26 new plants in the next 12 years. In short, Russia is paving its way to be one of the top uranium suppliers globally. Currently, Russia is one of the top sources of foreign uranium for the U.S.

So far Trump has not said much regarding the future of nuclear energy. His America First Energy Plan focused on overturning the Climate Action Plan and only mentioned nuclear energy once. If what Trump says about uranium signals what he understands about the nuclear energy sector, the U.S. might find itself in a serious quagmire.

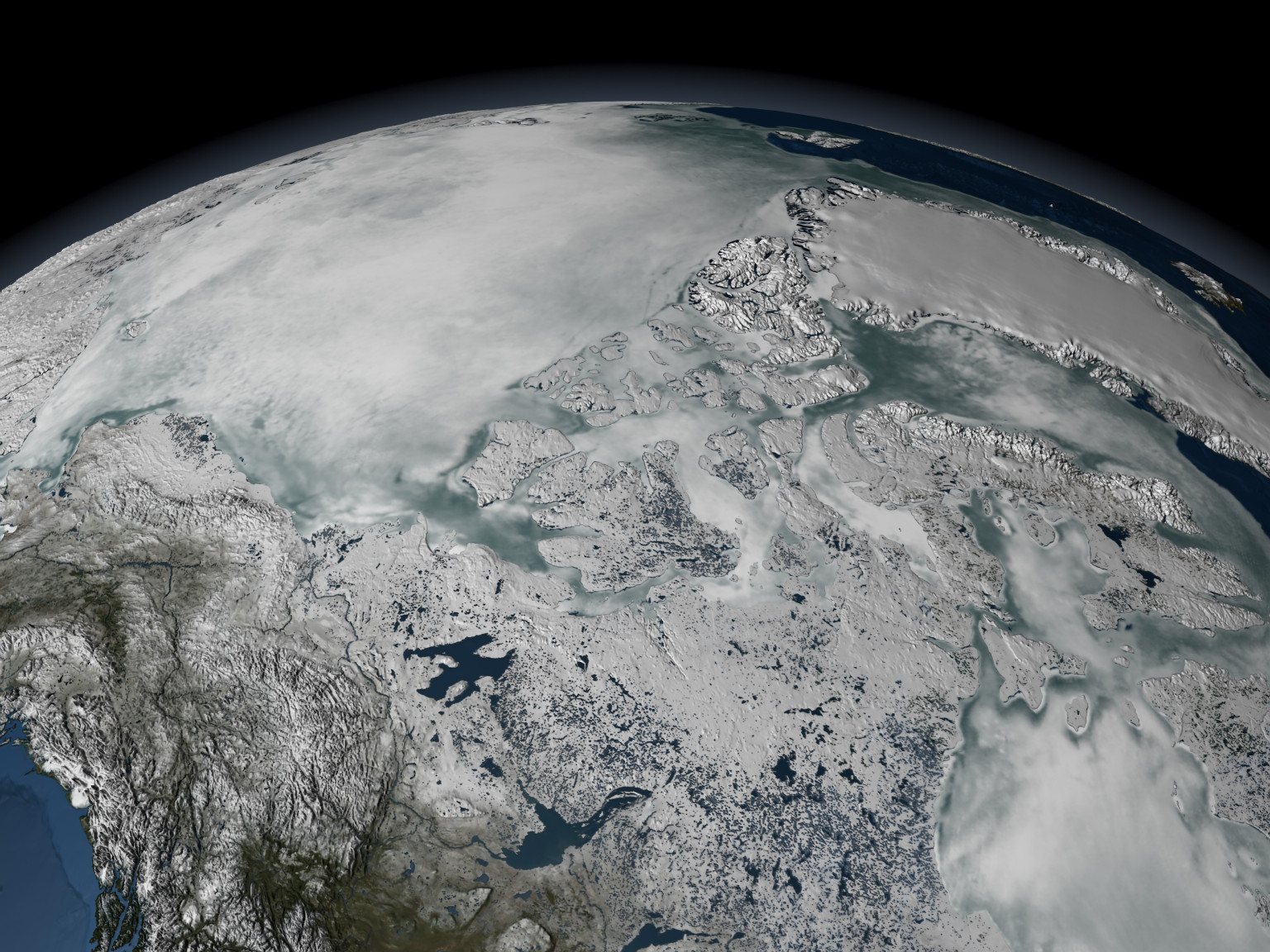

Photo: Nuclear Power (2005), Stefan Kuhn via Wikimedia. Licensed Under CC BY-SA 3.0

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.