In a ceremony at Rideau Hall on Tuesday, January 10, 2017, Minister of Global Affairs Chrystia Freeland and Minister of International Trade François-Philippe Champagne took their oaths of office:

I do solemnly and sincerely promise and swear that I will truly and faithfully, and to the best of my skill and knowledge, execute the powers and trusts reposed in me, so help me God.

So help them indeed. When it comes to Canada’s trade, they have their work cut out for them. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the newly-signed, multinational Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) face, respectively, renegotiation and cancellation. The Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), agreed with the EU after a tortuous final negotiation in Brussels, is still a long way from ratification. And there’s the small matter of a potential trade agreement with China.

The files on CETA, TPP, and China land on Francois-Philippe Champagne’s desk. Champagne, a former lawyer and international businessman, has to make the case for free trade in a period of slow growth and populist discontent. More than anything else, though, he will have to contend with the fact that foreign partners—and not Canada—will be the real decision-makers when it comes to major trade agreements. The TPP may be the largest trade agreement ever signed, but President Donald Trump has indicated that he has no intention of ratifying it. Without the US, the deal is dead. CETA, meanwhile, is signed, sealed, but undelivered. It recently cleared hurdles in the EU parliament and the German Constitutional Court, but must still be ratified by 28 EU members. With rising nationalism in Belgium, France and Germany, Canada will have to play a nervous game of wait-and-see.

Chyrstia Freeland may find her role running into the same problems. The former journalist’s move to Global Affairs attracted considerable attention, after what was widely perceived as a successful tenure at International Trade. Although she leaves much of the trade agenda behind, her mandate makes it clear that she will lead Canada in any discussion about the future of NAFTA. What, if anything, can she do about that future?

On the one hand, Freeland brings personal advantages to the role. Canada’s new top diplomat has a web of connections in Washington and New York from her time as a US-based financial reporter. She carries the cachet of successfully concluding CETA negotiations in Europe. And though she’s no fan of plutocrats like Trump (in fact, she wrote a book about them), Freeland can move in their circles and talk their language. Altogether, she has more going for her than Stéphane Dion, who, as a francophone intellectual with a prickly manner and a fondness for green energy, was never going to be an easy sell with Trump’s administration.

On the other hand, personality just might not make all that much difference. Renegotiating NAFTA, if it comes to that, is not going to be anything like the CETA talks. The US government is not Wallonia, and Canada’s trade negotiators won’t have 28 EU governments on their side, as they did in the final dash to conclude CETA. They might not even have Mexico, given that it is in Canada’s interest to seek different treatment from America’s southern neighbour. Our cabinet ministers are not going to be the most important pieces of the puzzle.

In fact, nor is Canada. In the great game of American trade policy, the Great White North is a minor player. NAFTA, like the Keystone XL pipeline, is not on the table for its economic merits, but for domestic reasons; a sacrifice to an electorate resentful of foreign imports and offshore jobs. Under these circumstances, personal connections are of limited use. When President Barack Obama needed to demonstrate his green credentials, his compatibility with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau did little to protect Keystone XL. The pipeline was scrapped just as Trudeau entered office.

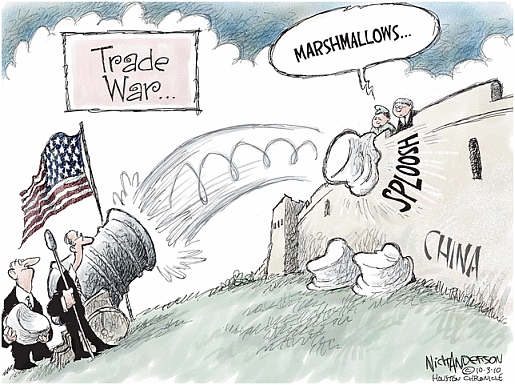

When it comes to Trump’s tough talk on NAFTA, his incoming officials have been clear: the target isn’t Canada—it’s Mexico. Secretary of Commerce nominee Wilbur Ross has claimed that Canadian trade with America is “better balanced” than Mexico’s, and in a confirmation hearing before the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transport Committee, his comments focused heavily on the US southern neighbour. Of course, NAFTA isn’t perfect. For every question the US raises about country of origin labeling, arbitration provisions, and natural resource pricing, Canadian critics can fire back that NAFTA drains Canada of water, oil, and natural gas. Renegotiation is not the conversation that most people wanted, but it could be a conversation worth having.

The risk of renegotiating, then, is not that America will punish Canada directly. The danger is that an American administration dead-set on Mexican concessions (anything, for example, that could be spun as payment for a certain wall) will throw the Canadian baby out with the NAFTA bathwater. It leaves Canadian officials with a classic dilemma: do they band together with Mexico, and risk handing everyone a worse deal, or do they strike out on their own, aim at a better agreement for Canada, and leave their erstwhile partners out in the cold? John Nash would have been proud.

Photo: “Old City Hall, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada” (2014) by Mariann Domonkos via Wikimedia. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.