When observing the power structures within China, what has become increasingly apparent over recent years is that Xi Jinping is overseeing an enormous consolidation of personal power in Beijing.

While the moves may fall short of a return to the cult of personality politics employed under Mao Zedong, it is clear that the post-Deng Xiaoping model of government via collective consensus by the Politburo is beginning to fracture. President Xi now controls the internal mechanics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), directly chairing major government committees on economic reform and national security. Likewise he has intervened in China’s foreign affairs far more than any other post-1979 leader.

of the most important domestic policy moves made under Xi has been the ‘Tiger and Flies’ anti-corruption campaign. The fissures this has opened are beginning to become visible within the heart of the Chinese establishment. While appearing monolithic to western eyes, the CCP is riven with factional rivalry, each with competing visions of 21st Century China. These internal rivalries that were once played out behind closed doors are becoming harder to ignore with the anti-corruption campaign beginning to resemble a soft coup. Its implications are leading China down a new and uncertain path.

One party, multiple factions

Since Deng Xiaoping sought to bring an end to the ‘one-man rule’, the CCP has developed at least three discernible factions, each centred on one of China’s former or current presidents. The first of these intra-party groups is the so-called “populist coalition”, referred to by Cheng Li of the Brookings Institution as the Tuanpai faction. This faction governed China from 2002 to 2012 under President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao.

Individuals within the Tuanpai faction such as former President Hu have modest origins, principally climbing through the ranks in the Communist Youth league to become local party leaders and regional administrators. They are associated with China’s rural interior and poorer provinces. Thus, the policy narratives and instincts of the Tuanpai are considered conservative in approach, opting for Communist solutions to economic and social challenges.

In a practical policy sense, this saw the elimination of agricultural taxes for China’s 900 million farmers in 2004. This resulted in massive infrastructure spendings to develop rural cities in the interior, making them competitive with cities like Shanghai on China’s Pacific east. Under Hu’s deputy, Premier Wen Jiabao, domestic policy was heavily focused on building affordable housing for China’s urban and rural poor. In the closing years of the Hu-Wen administration, the CCP committed $800 million USD to a government program to build 36 million housing units.

The second and third major factions, perhaps better known in Western circles, derive from the elitist “Taizidang coalition”, known as “the princelings”. This coalition was previously headed by former President Jiang Zemin but is now led by Xi Jinping. Its elitist reputation stems from the familial origins of many of the group’s leading figures and the wealth they acquired following Deng Xiaoping’s opening of China. Many figures within the princelings can attribute their current standing in the CCP to their fathers and grandfathers, who were veteran revolutionaries or high-ranking officials under Mao.

President Xi Jinping serves as a prime example. In contrast to Hu Jintao, Xi was born into privilege as the son of one of the influential families within the CCP. His father Xi Zhongxun remains a highly respected figure within the party hierarchy. Xi Zhongxun fought the Japanese in the 1930s, served as deputy to Mao in the 1960s and was instrumental in the 1980s in opening the Shenzhen Economic Zone.

In contrast to the Tuanpai, the Taizidang are seen to represent China’s burgeoning entrepreneurs and middle class in major eastern cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin. In terms of policy, the princelings are economic liberals. They favour private ownership of property assets and place greater confidence in the private sector. Due to their location on China’s eastern seaboard, the Taizidang also have the greatest experience in dealing with foreigners in government. A notable advantage as since 1991 foreign direct investment has played an increasingly larger role in shaping the Chinese economy.

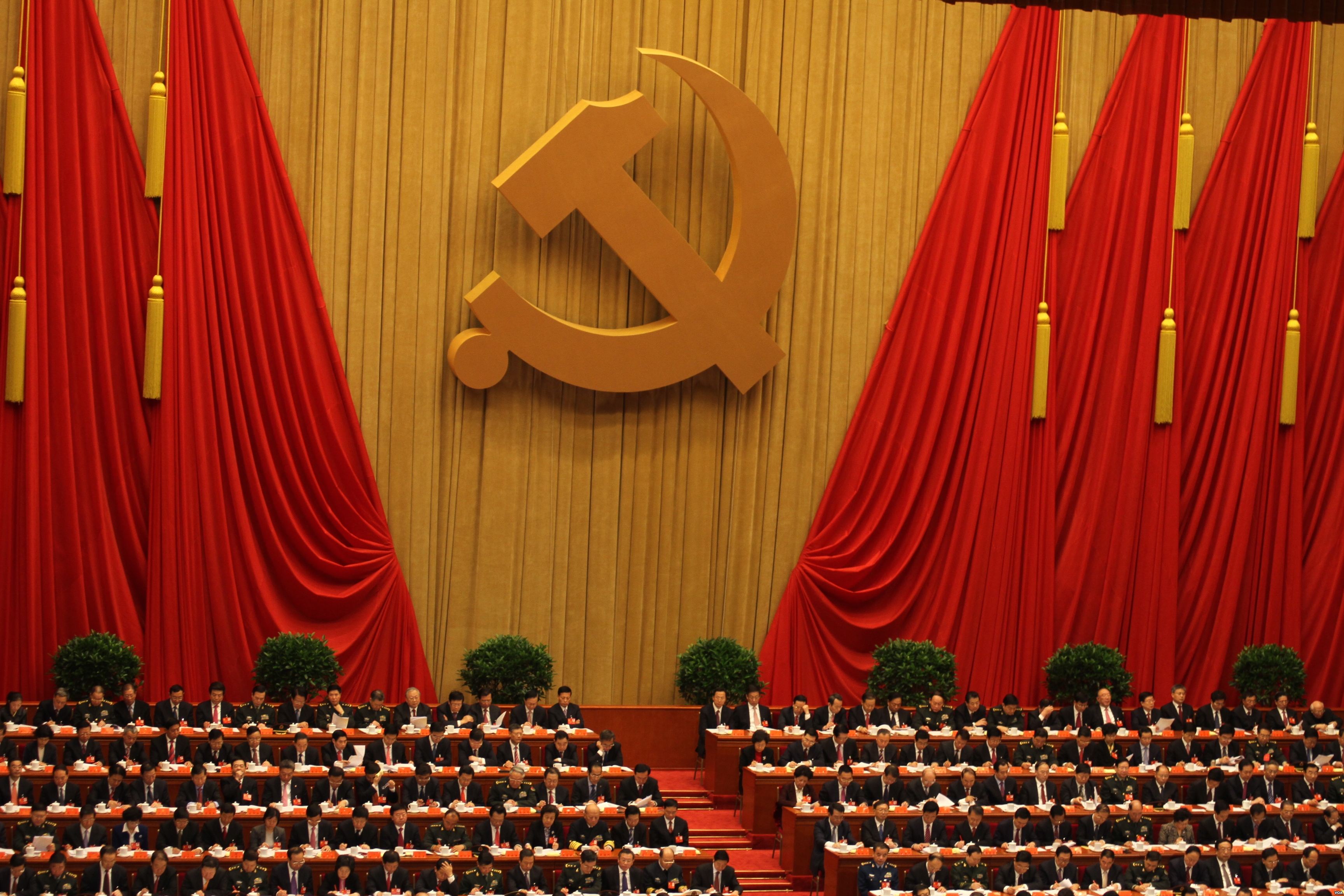

The 18th Party Congress in 2012, which oversaw the transfer of power, represented an enormous victory for the princelings over Hu Jintao’s successors. Six out of seven positions on the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) went to Xi loyalists, with only Li Keiqang representing any legacy of the Hu-Wen era. Viewed retrospectively, the 18th Party Congress heralded the beginnings of a dramatic centralization of power around Xi Jinping.

Undoing the legacy of Jiang Zemin

Within the Taizidang and the wider Chinese state lies a powerful clique of business, military and political interests known as the “Shanghai Gang”. They are known to be centred around Jiang Zemin, who served as Communist Party Secretary and President from 1989 to 2002. As their name implies, figures within the faction have close links to Jiang’s mayoralty of Shanghai and his time as Party Secretary. The Shanghai Gang rose to prominence in 1989 when then-Party Secretary Zhao Ziyang advocated talks with Tiananmen Square protesters and fell out of favour. Then the mayor of Shanghai, Jiang supplanted Zhao to become China’s premier, before ordering the use of the People’s Liberation Army to clear the Tiananmen Square protests.

From 1989 until very recently, Jiang Zemin dominated the CCP. This extended beyond his time as Party Secretary, filling the political vacuum left following the decline of Deng Xiaoping’s health and influence. Under Jiang, China saw major economic growth but also a proliferation of corruption and cronyism as he ensured close allies were placed in all major positions of power. Over the course of the decade, this process of cronyism saw the establishment of fiefdoms within the Chinese system, effectively creating a state within a state.

This parallel power structure encompassed China’s security apparatus under the rule of Luo Gan and then Zhou Yongkang. These Jiang loyalists expanded it into a behemoth with an annual budget of $120 billion USD, which is larger than the budgets of China’s military and paramilitary forces at the time. All this ensured the continuation of Jiang’s key policies, including the massive and systematic campaign of persecution he launched in April 1999 against the Falun Gong spiritual practice.

Following the transition to Hu Jintao’s leadership in 2002, Jiang remained as head of the Central Military Commission until 2004-2005, ensuring control of the People’s Liberation Army rested in his hands. When Jiang formally stepped down, he ensured that two loyalist generals, Guo Boxiong and in particular Xu Caihou, were given the roles of vice chairmen of the Central Military Commission. This ensured that Hu never had full control of China’s armed forces as Xu and Guo, like many of Jiang’s supporters, ran their own private armies and fiefdoms within the Chinese government yet outside the control of the formal CCP leadership.

Xi Jinping is aware of this, having served during the latter half of the Hu-Wen administration. Thus, much of the focus of Xi Jinping’s purge of the Communist Party over the last two and a half years has been on uprooting this political network. By removing those loyal to Jiang Zemin one at a time, Xi seeks to avoid the same fate that befell Hu Jintao’s presidency.

Securing the transfer of power in 2022

The pattern of arrests under Xi Jinping suggests a major coup is underway to remove the influence of Jiang Zemin from within the princeling faction and the wider CCP. In the last two years all key figures mentioned above including Xu Caihou and Guo Boxiong have been arrested and imprisoned. In December 2014, the leading figure behind Jiang’s security forces, Zhou Yongkang, was arrested and expelled from the party.

Recent news suggests that Jiang Zemin is himself now under investigation for corruption. In August 2015, sources in Beijing reported to the Epoch Times that China’s former president had been placed under ‘control measures’, restricting his freedom of movement. The groundwork may even be underway for a direct move against Jiang as the Chinese state-run People’s Daily is quoted as saying “Some leaders not only installed their cronies [in key positions] to create conditions for them to wield influence in future, but also wanted to intervene in the major issues of the organization they formerly worked for, even many years after they retired”.

Under the current trend of arrests, Xi is removing powerful and influential figures from within the Communist Party system in order to secure his position of power. High-level figures previously thought untouchable within the Communist Party, the People’s Liberation Army and the state bureaucracy have been brought to trial on charges of corruption. The political and societal effects are widespread, with Xi exerting a power and fear that hasn’t been seen in China in many years. The successful removal of Jiang Zemin’s power structure and the marginalising of Hu Jintao’s Tuanpai faction would leave Xi in an unassailable position ahead of the transfer of power in 2022.