With increasing political deadlock, economic stagnation, and a history of radical Islam in parts of the country, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s (BiH) potential as a hotbed of international and domestic terrorism is growing.

Bosnia’s systemic gridlock, combined with the country’s ethnic divisions, can breed extremism by sending the message to disaffected citizens that the legitimate channels for political reform are broken, and that working outside the system is the only way to make changes.

As part of the 1995 Dayton Accords, which ended the Bosnian War, the U.S. and its European allies helped implement Bosnia’s post-war political system. The agreement divided the country into two semi-independent regions: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska (RS), which both operate with a large degree of autonomy from the central government.

In the BiH political system, government positions are allocated based on ethnicity to prevent one group from dominating the others, as seen in the tripartite presidency, which consists of one Croat, one Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim), and one Serb. This power-sharing system was effective at ending the conflict, but its ethnic-based checks and balances has left the central government deadlocked on nearly every important issue.

The country’s political impasse has caused fragmentation along ethnic lines, threatening the integrity of the state, and in recent years has contributed to a rise in religious extremism and terrorism.

While the majority of Bosnia’s Muslims are either secular or moderate, a small percentage of them have adopted the ultraconservative Salafist or Wahhabist interpretations of Islam, which gained traction during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.

At that time, up to 6,000 foreign mujahideen fighters traveled to Bosnia to fight in solidarity with their besieged Muslim brothers. The Bosnian War acted as a testing ground for the mujahideen’s global jihadist ideology, which developed largely as a response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Many future al-Qaeda members—including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the principal architect of the 9/11 attacks, and two of the 19 hijackers—gained combat experience in Bosnia.

While the Dayton Accords claimed to have successfully extradited all of the foreign fighters at the end of the war, some fighters and, more importantly, their ideas remained.

Recent reports of up to 150 Bosnian men traveling to the Middle East to join militant organizations, such as ISIS and al-Nusra Front, point to the lingering influence of mujahideen ideology. This number is disproportionately large for a country with a population of only 3.8 million.

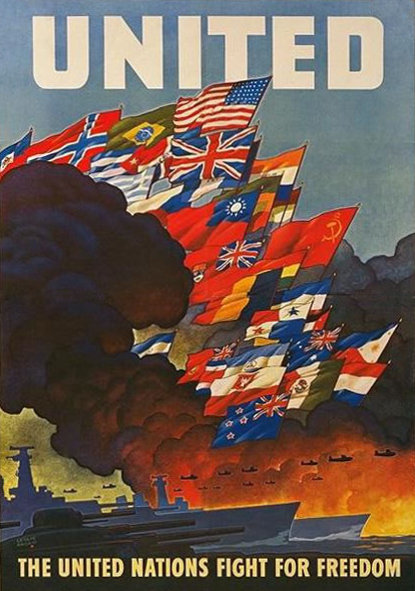

These foreign fighters often come from religiously conservative villages in isolated rural areas, where many ex-mujahideen are said to reside. Villages like Gornja Maoca highlight the pockets of extremism that exist in BiH. Indeed, ISIS flags have been displayed at entrances to the village (pictured above), as well as numerous residences.

In these rural areas, radical clerics are calling on young Bosnians to join ISIS and other jihadist groups. Bilal Bosnic, for example, was arrested in September 2014, along with 16 others on charges of financing, organizing, and recruiting Bosnians to fight abroad.

Last year, BiH authorities introduced jail terms of up to 10 years for citizens who recruit fighters or engage in foreign wars, in an attempt to combat the growing problem. However, widespread corruption in the country’s law enforcement and justice systems has caused concerns over the enforcement of these new laws.

With their prior combat experience from the Yugoslav wars, some Bosnian jihadists have even taken command positions in the Middle East. Nusret Imamovic, leader of the main Wahhabi Islamist cell in Bosnia, traveled to fight in Syria and is believed to be the third most powerful member of the al-Nusra Front terrorist group.

While many of Bosnia’s radicals have been drawn to the Middle East to carry out jihad, the nation also faces terrorist threats at home. In October 2011, a suspected radical Islamist attacked the US Embassy in Sarajevo, seriously wounding a police officer.

Most recently, 24-year-old Nerdin Ibric opened fire inside a police station in the BiH Serb town of Zvornik while shouting “Allahu akbar”, which is Arabic for “God is great”. Ibric killed one officer and wounded two others.

Following the Zvornik attack, the Republika Srpska government launched a comprehensive campaign to find and arrest Islamic terrorists. Muslim Bosniak politicians have criticized Operation Ruben for stirring the nation’s deep ethnic tensions. Bosniak leaders claim that Serb police are abusing their power in response to the terrorist threat and unjustly infringing on the rights of Muslims. One Bosniak MP stated “Bosniaks are in fear and feel like it’s 1992,” referencing the year the ethnic-based Yugoslav wars erupted.

The Zvornik attack has also fueled ethnic tensions among BiH Serbs. Following this incident, Serb leader Milorad Dodik reignited calls for Republika Srpska’s independence and pushed for the creation of its own intelligence service, calling the country’s central institutions “useless” in the fight against terrorism.

Responses to the Zvornik attack not only illustrate BiH’s deep-rooted ethnic tensions, but also highlight how its central institutions are largely incapable of addressing the roots of extremism and dealing with the growing terrorism problem. The longstanding epidemic of political deadlock, corruption, and economic stagnation, combined with BiH’s history of ethnic violence, has created an environment ripe for extremism.

Unless steps are taken to reform the political system, address the nation’s economic tribulations, and integrate radical communities, the threat is unlikely to subside.