The International Criminal Court (ICC) has dropped charges against Kenyan President Uhruru Kenyatta. Kenyatta had been charged with crimes against humanity for the violence that followed the country’s 2007 elections, resulting in the death of 1,200 people and the displacement of 600,000.

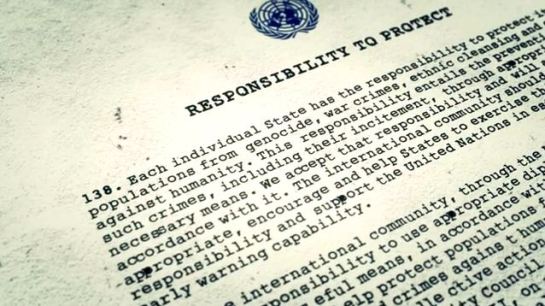

This recent case illuminates the limited capabilities of the ICC. Foundedto persecute individuals, who commit international crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes, its ability to function as a true international criminal court is seriously limited.

Since its establishment in 2002, the ICC has successfully convicted two Congolese warlords. Many of those who have been indicted, such as Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir and former Libyan leader Saif al-Islam Gaddafi for crimes against humanity have never been apprehended.

Complicating the proceedings are accusations of bribery and intimidation. Conducting a fair trial when the accused is a head of state is extremely difficult. Often, as in the case of Kenyatta, the accused is able to use his position of power to influence the proceedings.

The inability of the Court to effectively enforce its findings is further limited by its narrow jurisdiction. While the court may exercise jurisdiction over individuals accused of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide, the Court’s jurisdiction must be recognized by the accused’s home country. Many of the world’s most influential countries do not recognize its authority, such as the U.S., China, India and Russia, which is discouraging. On the other hand, the number of States Parties to the ICC is significant, showing their willingness and commitment to abide by Court’s actions.

The ICC is obviously a work in progress. Though it is regularly criticized for its many limitations and failings, it remains an important international body, dedicated to the international protection of human rights