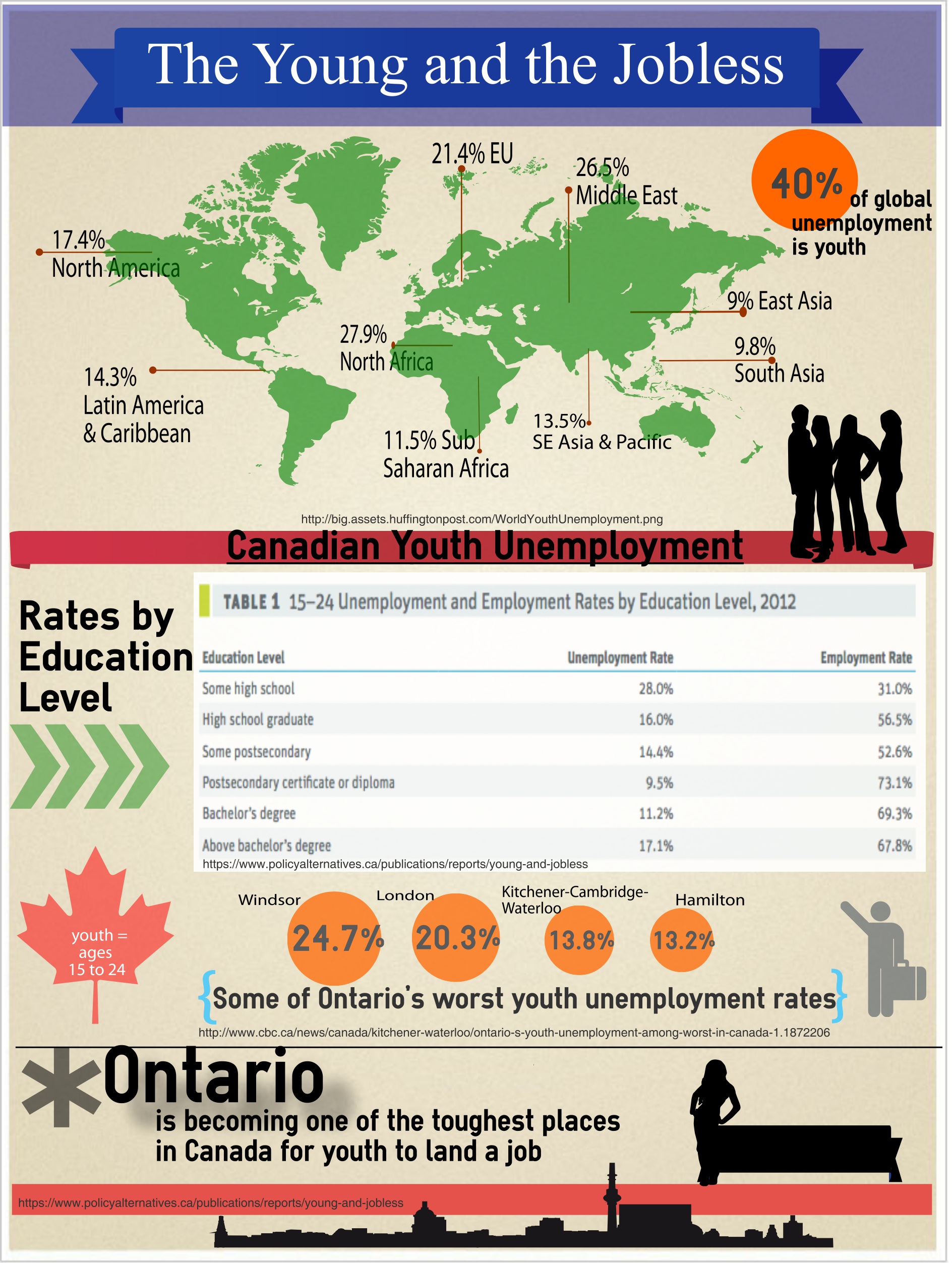

The issue of sexual harassment and exploitation has been a subject that militaries and organizations around the world have had to grapple with for decades, NATO being no exception. However, in the past couple of years, NATO has made a concerted effort to address gender disparities and sexual exploitation and harassment. In 2014 the organization introduced its Report on Gender Perspectives, which investigated the position of women in NATO member militaries and explored the issue of sexual violence.

The report which was published yearly between 2014 and 2017, allowed different NATO states and partners to evaluate how they were doing on issues concerning gender, such as incorporation of women into higher ranks, distribution of women in different forces, and sexual exploitation and abuse. In 2017, the report found that women still made up a marginal percentage of member militaries, falling at around 11%. However, of all the reported instances of sexual harassment and exploitation, women accounted for over 90% of the complaints. This report, along with other information, cumulated in the creation of NATOs first ever Policy on Preventing and Responding to Sexual Exploitation and Abuse in early 2020.

One Step Forward: takeaways from the policy

Before the introduction of the policy, institutions including Queen University’s Centre for International and Defence Policy had recommended that NATO would eventually have to take on the issue of sexual assault and harassment. In 2018, the Centre issued a number of recommendations including providing consistent language and definitions around sexual assault, exploitation and harassment that could be applied across member states. The central argument was that by working together, the member states could develop a sense of best practices and universal standards that could be applied.

This was especially important considering that in 2017 just over 80% of member states had training to address sexual harassment in their forces, with only 70% having formal strategies and mechanisms meant to prevent and report on harassment and abuse. This means that as of 2018, 30% of member states within NATO still lacked formal structures and mechanisms to report sexual harassment and abuse. This is a particularly concerning problem because NATO has traditionally argued that its existing ‘guidelines’ and state policies addressed the issue sufficiently.

This division amongst NATO members illuminates one of the major problems that exist in the new NATO policy, specifically, the policies’ decision to place the burden of fighting sexual misconduct on member states rather than NATO itself. This is evident in the decision of NATO to place the onus on the state for vetting and educating national militaries on issues surrounding sexual misconduct, creating a two-fold problem. On one hand, states could be convinced to overlook some negative behaviour in their vetting program, which could place a person with a history of sexual exploitation in a NATO role. On the other hand, a lack of consistency in training could not only create differences in what people believe constitutes sexual exploitation or abuse, thus creating problems within multi-national forces where jurisdictional issues could become diplomatic nightmares.

Another challenge posed by the policy structure’s focus on state control is an issue of jurisdiction and consistency, in particular its decision to make investigation and discipline a national concern rather than a NATO one. This means that member states are responsible for all investigations of sexual misconduct complaints, with NATO itself only providing preliminary investigations. It is not difficult to imagine that this could prove very problematic if an assault took place between members of different nations’ militaries or on a member’s military base. The system would make jurisdiction an incredibly difficult issue to address and could have potentially devastating consequences. Another possible problem that arises out of this is consistency. If NATO does not place a set guideline on standards of investigation or punishment, it is likely that regional differences would cause wide variation in the nature, depth, and result of said investigations.

Despite these challenges, the NATO policy does make a number of positive changes. The policy makes particular reference to the problem of power imbalances in sexual relationships, stating: “sexual relationships based on inherently unequal power dynamics are a form of sexual exploitation.” This sends a strong message that there is no possible acceptable reason for a sexual relationship between a superior and subordinate and serves as a strong deterrent to those forms of relationships. Likewise, the policy notes that sexual harassment and exploitation is against the inherent principles of NATO and puts the organization and its missions at risk. Thus, the policy ensures that possible risks be addressed in any mission planning and that all possible efforts be made to mitigate the danger.

Towards a better model: The UN

NATO is not the only international institution that has recently sought to strengthen its policies on sexual harassment and exploitation. The UN has been more successful in putting together a fully independent framework and methodology to address the issue. Like NATO, the UN has focused on assessing and mitigating possible risks of sexual harassment and exploitation and has worked to educate people about their responsibilities related to reporting these behaviours. However, whereas NATO sought to incorporate this into existing communication frameworks and systems, the UN employed an educational campaign around the issue. This has the advantage of truly teaching UN forces and staff about what constitutes sexual misconduct and teaching them the appropriate reporting structure and the mechanisms that are in place.

Unlike NATO, the UN also decided to put into place specific training and uniform standards surrounding the issue, enforcing training both before and during deployment based on the UN Standards of Conduct to address these issues. Moreover, while NATO uses member nations to screen their members for possible red flags and records, the UN is very specific in checking for any history of exploitation or abuse. In a strong message to the public and their own forces, the UN strictly prohibit anyone with a history of sexual exploitation or abuse from serving in the UN or UN organizations.

What to do?

In recent years, NATO has made great strides to address issues of sexual violence and harassment. However, the nature of NATO, especially the priority given to state sovereignty, has made it difficult for the organization to implement policies sufficiently capable of preventing and punishing sexual exploitation and abuse. The recent model put forth by the UN provides a strong framework for further advancing NATO’s approach to this issue. Having taken an important first step, it is now time for NATO to take the second.

Photo: Sailors aboard USS Chancellorsville commemorate sexual assault prevention month (2016), by US Navy via Flickr.

<p style=”line-height: 1.8; font-size: 17px; font-family: Philosopher; text-align: left;”><em>Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.</em></p>