Daniel Park- Program Editor, Arc of Crisis

A week ago, the first and much-anticipated inter-Korean dialogue took place at the truce village of Panmunjom after two years of diplomatic hiatus between the two countries. Against the backdrop of North Korea’s ever-advancing nuclear and ICBM arsenal, war rhetoric, and President Trump’s recent call to end the “era of strategic patience,” the dialogue was an unexpected and hopeful attempt at restoring rapprochement in the Korean peninsula. The dialogue indeed signaled some signs of thaw: North Korea agreed to participate in the upcoming Pyeongchang Winter Olympics reopen a military hotline in South Korea; resume reunions for families split during the Korean War; and reopen a military hotline with Seoul.

However, the puzzling decision to not invite China, and the emboldened, collective push to enforce more sanctions against Pyongyang to abandon its nuclear ambitions at the Vancouver foreign ministers’ meeting signals a dim prospect for peace. Although Beijing does not approve of Pyongyang’s nuclear brinkmanship, preventing regime collapse has always been a greater priority over denuclearization. Thus, while Beijing wields considerable diplomatic and economic leverage against Pyongyang, it is not a strong proponent of choking North Korea’s already poor economy. Not extending an invitation to Beijing impedes future cooperation with the Chinese on the North Korean question, and provides a greater justification for Beijing to maintain the status quo.

Lastly, past American-led intervention against non-nuclear adversaries such as Serbia, Iraq and especially Libya underscored to Pyongyang that the development of nuclear weapons is the best insurance against a potential regime-change war perpetrated by the U.S. As a rational actor, Pyongyang will thus never denuclearize. Unless, theoretically, the regime exhausts its resources. However, emboldening sanctions have historically been futile. It is unclear whether the sanctions are perfunctory or Pyongyang is impervious to any economic blockade. Nevertheless, Pyongyang’s nuclear programme has flourished in recent years at an alarming rate – despite the ever-mounting sanctions.

The international community must resort to deepening cooperation with China and fostering a less hostile and open environment for Pyongyang to successfully deliver a productive dialogue in pursuit of peace in the Korean peninsula.

Lionel Widmer- Program Editor, Canada’s NATO

In a time where a radical rogue state is threatening stability and peace, Lester B. Pearson’s vision for the contribution of middle powers to peace making and keeping has never been so relevant. Indeed, the recent summit in Vancouver was an opportunity for middle powers to do just that.

The countries who were, and were not, at the summit have been the source of much scrutiny. Many of the countries that fought alongside South Korea in the Korean War, as well as South Korea itself, were at the summit. Whereas, North Korea and its sympathizers, such as Russia and China, were conspicuous in their absence.

The countries present all made a commitment to maintain strict sanctions on North Korea until it abandoned its nuclear program. While this could simply be seen as a meeting of allies against North Korea, it can also be seen as middle powers showing the Rogue Nation what they will not stand for.

Canada has maintained its position that it would rather seek a diplomatic end to the crisis on the Korean Peninsula. This is not an empty assurance: they are one of the few countries that North Korea is willing to send its students to for an education and, perhaps more importantly, they still refuse to be a part of the US Ballistic Missile Defense program. Canada’s reluctance to participate in this program is a clear indicator that it is not preparing for a war with North Korea. However, if Canada wants to truly make a difference as a mediator – they will have to find a way to bring Russia, China, or North Korea to the table in the next summit.

Yun Sik (James) Hwang- Program Editor, International Business and Economy

Sanctions over Sanctions: What Now?

The 2018 Vancouver summit, co-hosted by Canada and the United States of America, was an effort to restore peaceful diplomacy over the “Korean Roulette,” a call to the global community to pressure Pyongyang in the pursuit of denuclearization. This gathering between Canada, the U.S., the Republic of Korea (or South Korea), and 17 other nations in Vancouver sought to thaw current tensions with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea).

The solution to acquire peace, however, seems to require stricter, tighter, and more intense pressure on North Korea. Both U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kono urged invited nations to promote increased isolation on Kim Jong-un, while the U.S. Air Force deployed six additional nuclear-capable B-52 Stratofortress bombers and 300 soldiers to Andersen Air Force Base, located in Guam. With three B-2 Spirit bombers already stationed in Guam, this was a direct message to North Korea that they are serious about countering the threat from Pyongyang.

Although there were talks of peace, as hinted by South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha, it is evident that the anxiety of war continues to linger, as neither Kim nor President Trump is expected to recognize that war is pointless. There is, at the very least, the reassurance that the 20 countries which participated in the Korean War took part in the deliberations, providing a sign of unity and initiative to establish a peaceful approach. But it is also true that this summit sends a warning to Russia and China, the two uninvited nations, that siding with North Korea equals isolation.

Daniel Jung- Program Editor, Society, Culture and International Relations

Ever since November 29th, when the North Korean (DPRK) regime demonstrated that it has the potential to impact the east coast of America, foreign ministries have been in a state of high alert. Their collective concerns encouraged them to cooperate in multilateral institutions through the UN and through international summits. One such summit was the Vancouver Summit (January 15th to 16th ), during which world leaders received another opportunity to deal with security threats posed by the DPRK.

This summit happened at a critical time, as not only are the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics currently being planned, but also, a false warning of an impending DPRK missile was broadcasted through the Hawili FCC , and through NHK Japan.

As the details of these international summits are disclosed, I cannot help but recall the Six Party Talks, which took place from 2003 to 2007, where the Koreas, China, Japan, the US, and Russia reached an agreement that the DPRK would abandon its nuclear weapons development in exchange for economic aid. As we all know, these agreements were not maintained by the DPRK, despite its representatives participating actively at the negotiating tables. Comparing the actions of the DPRK regime back in 2003, 2007 to 2017, one has to wonder how much weight these multilateral summits actually carry.

Although the summit was an opportunity to further deter North Korea from continuing its hostile stand-off against the US, this opportunity was missed with Russia, China and DPRK not being present at the negotiating table. With Russian and Chinese state television heavily critical of this summit, one may even argue that it resurrects the dynamics of the Cold War.

Changsung Lee- Visiting Scholar From the South Korean Ministry of Unification

Although the Vancouver Summit did not promote concrete measures to deter North Korea’s provocation, it was meaningful in the sense that the pressure of the international community toward North Korea has the potential to change its behaviour.

First, when the possibility of war continues on the Korean peninsula, the summit of foreign ministers of the nations who composed the UN Command is symbolic in its own right. Second, despite the improvement of relations between the two Koreas, such as the inter-Korean talks, it has been confirmed that the sanctions are an attempt to solve the nuclear issue. It means that the clear message that “As long as North Korea does not change fundamentally, international sanctions will continue” was sent to North Korea. Third, in terms of putting actual pressure on North Korea, the issue of maritime interdiction was discussed during the summit. This is because North Korea is most concerned about the sea blockade. In fact, North Korea has consistently stated that the containment of North Korea is in fact a declaration of war.

Marwan Elghamry- Program Editor, Emerging Security

Although seemingly optimistic at first, the North Korea Summit in Vancouver was hardly innovative. While the central idea of increased sanctions may have an eventual impact on North Korea’s nuclear aspirations, the same cannot be said about its aspirations in the cyber world. Its known involvement with the Sony hacks and its recent connection with cryptocurrency hacks in South Korea are both proof of the state’s engagement with cyber campaigns as a means of political interaction.

Whether intensified pressure on part of the West will decelerate North Korea’s nuclear program is a complex question; whether it will impede its cyber security campaigns poses an increasingly more complex one. Nonetheless, it is known that while mutually-assured destruction serves as a deterrent against nuclear warfare, there is not much which stands against cyber warfare. Similarly, the resources required to propel a cyber campaign are insignificant when compared to those required for a nuclear campaign. This makes cyber warfare—despite being far less destructive—an equally impending threat as nuclear warfare. That said, the conceived objective of constantly increasing sanctions on the state, although potentially encouraging nuclear disarmament in the future, may not be as effective in cyber disarmament.

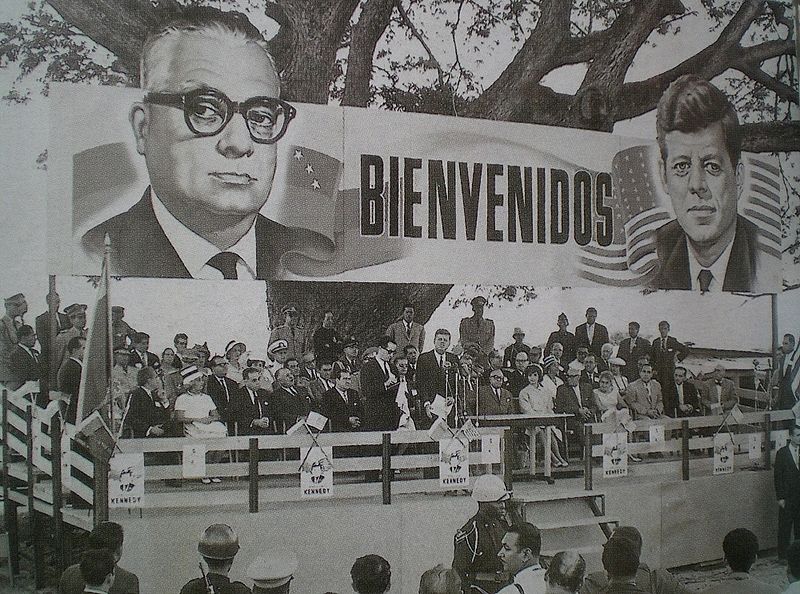

Photo: Secretary Tillerson Participates in the Korean Peninsula Summit (2018) by Flickr Via U.S. Department of State Link

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.