European energy security, especially the diversification of sources of supply of natural gas, increasingly depends on the South Caucasus countries of Georgia and Azerbaijan. Russia is building the NordStream Two and TurkStream pipelines in order to secure European Union (EU) dependence on Russian gas for decades to come.

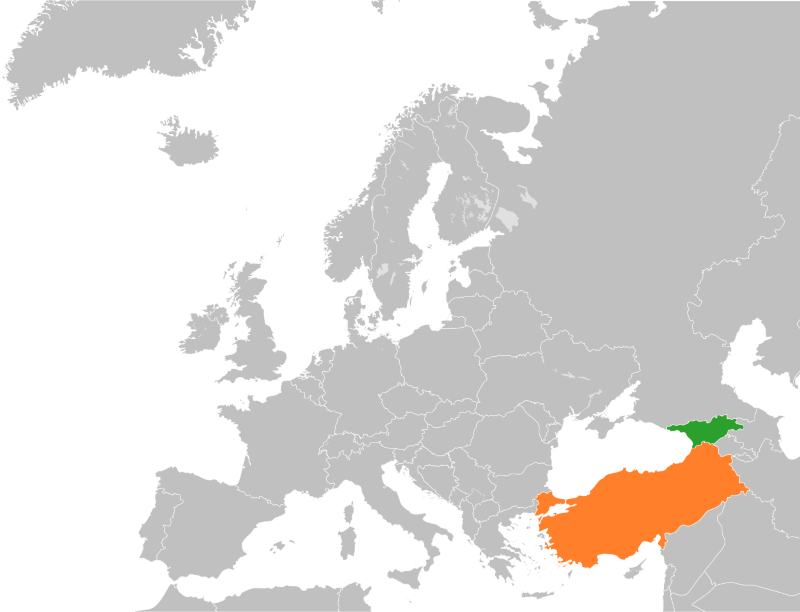

Because of its unique geographical situation, Georgia in particular has played a key role in the diversification of sources of energy supply for the EU through the Southern Gas Corridor, which runs from the Caspian Sea through the South Caucasus and Turkey to Europe.

Georgia has taken important steps in the last five years to draw closer to the EU. In June 2014, it signed an Association Agreement with the EU, which entered into forced in July 2016. Then in October 2016, Georgia joined the Energy Community, and it formally ratified this accession in April 2017. The Energy Community is an international organization that the EU established in 2005 in order to extend its internal energy market to EU non-members to its south and east.

Throughout 2018, the signs in favor of the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline (TCGP) have been accumulating: the Caspian Convention has been signed; the Azerbaijan-Georgia-Romania Interconnector (AGRI) project for compressed or liquefied natural gas from Azerbaijan has died once more; Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan leaders and ministers have been holding dedicated talks planning for TCGP implementation, which is now an explicit Turkmen state policy; and subtle changes in the information policy of Azerbaijani media suggest that Baku is now fully behind the project.

Indeed, construction of the TCGP will only help with the implementation of Prime Minister Mamuka Bakhtadze’s package of reforms for Georgia’s energy sector. One could even say that the TCGP would assure the success of those reforms, and such success is difficult to envision without the TCGP. This is because introduction of Turkmen natural gas into the Georgian gas transmission system would nearly guarantee the liberalization of the country’s gas market regulation.

The TCGP is a strategic project for both Turkey and Georgia. It can be compared to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil export pipeline, which established and reinforced the independence of the participating countries, and which also happened to be very advantageous commercially.

The TCGP, running through Georgia and with the White Stream pipeline extending under the Black Sea, would not only attract foreign direct investment to the country. It would also increase the security of its gas supply, also for Turkey since the first string of TCGP would connect to the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP).

Georgia is a major independent actor in the TCGP project, because Turkmenistan does not generally allow production-sharing agreements. This means that oil and gas majors will not take the necessary risks to develop pipelines for Turkmenistan’s energy, which it sells at its border.

Because of that, the European Commission and the Georgian government have cooperated to innovate a new financial structure, co-funding administrative support and the pre-FEED and engineering studies necessary to define transit costs, permitting shippers to negotiate contracts with Turkmenistan.

The EU has publicly recognized Georgia’s involvement as an essential partner in this respect. The European Commission has selected the TCGP as a Project of Common Interest, qualifying it for preferential funding.

The next three to five years are a key window of opportunity to set the table for what will come next, until the middle of the century. Building upon the successful Georgian reforms motivated by the BTC, the TCGP will clarify and stabilize the situation in Georgia both economically and politically. In the process, it will extend Turkish influence onto the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea in a positive way.

With TCGP realized, the promise of the undersea Kazakhstan-Azerbaijan Trans-Caspian Oil Pipeline (TCOP) will be encouraged, including the Kazakhstan-Caspian Transportation System pipeline to be built inside Kazakhstan as part of the TCOP.

That oil would also transit to Georgia’s Black Sea coast, from where tankers would take it to Odessa, where it would enter the planned Euro-Asian Oil Transportation Corridor, which if completed would enable it eventually to land in the Polish port of Gdansk for world export. This oil could also be diverted via Baku to Ceyhan via the BTC pipeline, a version designated as the ABC pipeline (for Aktau-Baku-Ceyhan).

Such developments would make it possible for Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, and even Uzbekistan, to rely politically on Turkey more, in order to balance among encroachments by Russian, Chinese, and Iranian influences in Central Asia. Because of their geographic situation, the Central Asian states explicitly and consciously follow a “multi-vectorial” foreign policy, seeking as many partners as possible in order to diminish the leverage of any one of them.

Photo: “Georgia Turkey Locator map” (March 20, 2015) by Nordwestern via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.