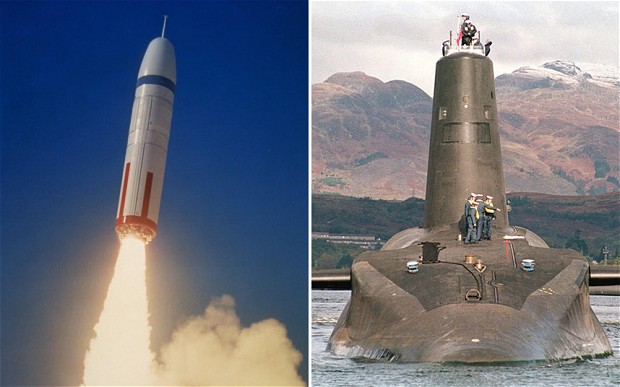

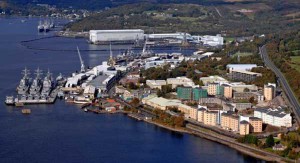

One of the central issues regarding the Scottish independence debate is the UK’s Trident nuclear missile arsenal, located entirely in Scotland. Four Vanguard-class submarines armed with the Trident II D-5 ballistic missiles use the specially-built Naval Base Clyde – located some 40 kilometers north-west of Glasgow – as their centre of operations. The location of the base on the shores of Gare Loch allows for easy access to the Atlantic, and the surrounding landmass provides relative protection. Naval Base Clyde also employs some 6,700 people, and as would be expected from an installation its size, has many knock-on effects on the surrounding area’s economy. This status quo, however, is threatened by potential Scottish independence.

One of the goals of the pro-independence coalition (comprising the Scottish National Party, the Scottish Socialist Party and the Scottish Green party) in the fight for secession is the removal of nuclear weapons from Scottish soil and waters, and to establish Scotland as a nuclear-free state. Such plans have given cause for speculation as to what the UK’s contingency plan is if Scotland were to kick out Trident. At first sight it would appear that the UK would have to face the prospect of relocating its arsenal south of the border. Although Gare Loch is an ideal location for the submarine fleet and base, the UK is by no means short of alternative sites, with the naval bases at Falmouth and Devonport being two obvious and supposedly viable candidates.

What is short, however, are the funds to relocate. Considering the government has planned to cut a further 30,000 personnel from the armed forces by 2020, it comes as little surprise that some advocate dropping the programme altogether and spending the billions of pounds it would cost to relocate the arsenal some other way. Figures for the cost of relocation vary significantly, but the lowest quoted is £2.5 billion.

Naval Base Clyde

Just how realistic is it to expect the UK to consider this option seriously? Relinquishing Trident without replacing it would mean being the only member of the Security Council not to own nuclear weapons. Moreover, it would mean being the only one to have owned them and voluntarily given them up (albeit under pressure). Those in favour of the abandonment of the program are quick to point out that maintaining a nuclear arsenal belies today’s geopolitical situations: the destructive power of nuclear warheads are hardly suited to the threat of stateless terror groups. Such reasoning is only likely to land on deaf ears, however: while it may play its part in deterring non-nuclear states from pursuing a costly nuclear weapons program now that the Cold War is over, it is very unlikely to push a world power the caliber of the UK to give up its nuclear deterrent capabilities. Doing so would effectively mean a drastic loss of prestige, authority and credibility as a military power.

Perhaps a more realistic option is the possibility of striking a deal with an independent Scotland, whereby the UK would be allowed to keep its nuclear arsenal on Scottish soil – possibly in exchange for a currency union (the SNP being keen on keeping the pound). Such an agreement would mirror the nuclear umbrella accord the US has with Japan, South Korea, Australia or indeed that the three nuclear-armed NATO states of France, the US and the UK have with the rest of the members. However such a deal would not only require Scotland to back-pedal on its resolute pledge to become nuclear-free, but it would also entail the UK holding its most important military asset on foreign soil. As an extension to this point, suggestions that the UK might seek to place its nuclear weapons on French or US soil are equally dubious.

Nevertheless, the UK announced its decision to go ahead with a £3 billion investment in Naval Base Clyde, with plans to extend the nuclear submarine fleet to eleven and in the process create a further 1,500 jobs in Faslane. This would suggest a considerable degree of confidence in either a ‘no’ vote in September or in Westminster’s ability to broker a deal with an independent Scotland.

The first article in this series of three laid out Scotland’s security prospects in the event of independence in less than a month. The conclusion was that Alex Salmond’s insistence that it needn’t be a drawn-out and complex matter is bordering on the wishful, if not the naïve. Beyond the point on Trident (which is admittedly Westminster’s problem a lot more than it is Scotland’s), there is the NATO membership facet to consider.

There is no question of just how beneficial joining NATO after independence would be were secession achieved. However despite Mr. Salmond’s apparent conviction, membership would be far from a given. Not only would Scotland have to apply as a new state, but also as one that rejects nuclear weapons outright and jeopardizes one of the NATO founding states’ nuclear integrity. Scotland’s apparent intransigence regarding nuclear weapons and NATO’s nature as a fundamentally nuclear pact-based alliance are simply incompatible, and an exception would have to be made if Scotland were to gain membership.

It seems that the pro-independence coalition has its mind set on emulating New Zealand in 1983 and making Scotland a nuclear-free zone, regardless of the implications this may have on its plans to join NATO. As for the impact its anti-nuclear policy would have on the UK, as far as Mr. Salmond and company are concerned, the UK made its bed by placing Trident in Scotland in the first place: the fallout and what happens to Trident (and by extension the UK) is of no concern to Scotland. Whether this sort of belligerent and non-compliant attitude stands to create a rift between the two countries in the event of independence is doubtful, but it would seem that non-Scottish Britons wouldn’t be all too willing to forgive and forget if Scotland votes no.