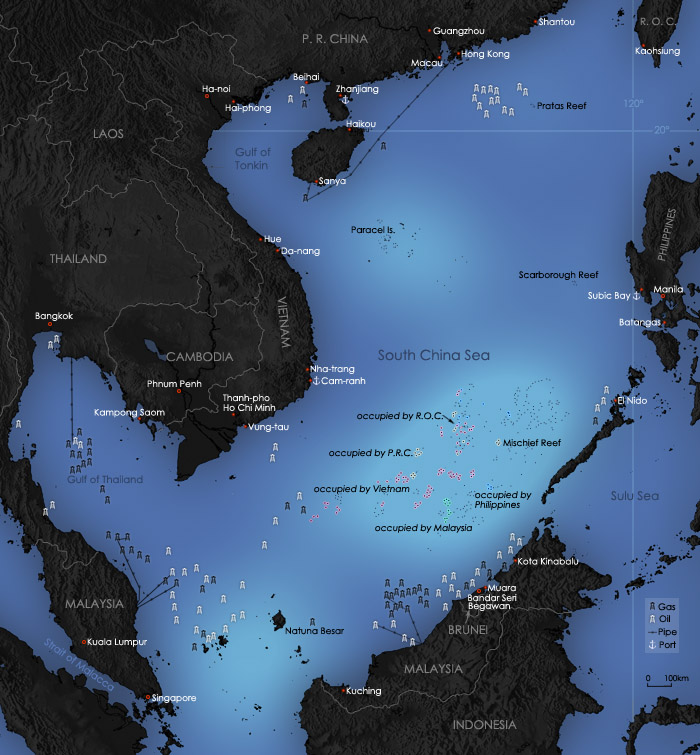

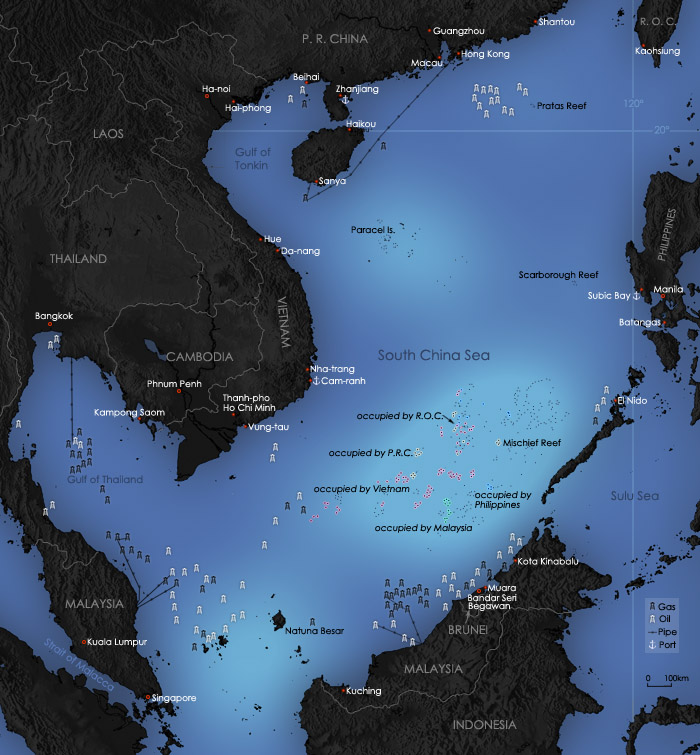

The South China Sea has been viewed as a potential flash-point for conflict within the Asia-Pacific region since the end of the Cold War. Within this body of water lie many territorial disputes with multiple overlapping claimants, including a large number which have been frozen in place since the Second World War. The rise of China as a global superpower has recently led to increased discussions concerning Beijing’s intentions in this strategic area and its increased capabilities to project power.

Concurrent with the rise of China, we are also witnessing littoral states such as Vietnam and the Philippines exhibiting an increasingly active maritime presence in the South China Sea. Key events such as confrontation with the HYSY981 oil rig off the Paracel Islands or the seizure of Scarborough Shoal have seen Manila and Hanoi encounter an increasingly assertive China.This combination of territorial disputes combined with assertive maritime maneuvers has been described as a ‘Sarajevo in the South China Sea’, a confluence of regional tensions akin to the Balkans. This is correctly viewed as flawed, importing a European perspective on an Asian flash point, nevertheless this area is a key point of concern.

The South China Sea, with its numerous island chains and coral atolls, is believed to be home to vast reserves of untapped hydrocarbons, located below the seabed thus at a minimum serves as a flash point for competition. As tensions between Vietnam and China in May and June of 2014 highlighted, Chinese exploratory attempts via the HYSY 981 platform within the South China Sea prompted pronounced levels of domestic nationalism between these two two Asian states. According to one report Vietnamese fishing vessels rammed Chinese coastguard and fishing ships over 1,547 times. This rapid deterioration of Sino-Vietnamese relations, comes in spite of increasingly close economic ties, $50.21 billion in trade in 2013.

There exists an uneasy balance in the South China Sea, diplomatic attempts to garner increased foreign direct investment (FDI) from China by states such as Vietnam and the Philippines is mooted by concerns over increased activity and a sizable maritime presence in the South China Sea by Beijing, not seen since the Qing Dynasty of the early 18th Century.

In understanding the escalation in tensions in Sino-Vietnamese relations this past year, the nature of the Chinese presence is notable. Beijing’s presence was not of a military nature but an economic one. The arrival of the HYSY 981 platform in the Paracel Islands was accompanied by a large flotilla of Chinese flagged fishing vessels and other such craft, attempting to legitimize Beijing’s economic presence in the South China Sea in a pattern also witnessed in the East China Sea with Japan.

China post-2008 has increasingly sought to readdress the structure of the Asia-Pacific’s economic and political balance of power. In the short term, increasing China’s influence in the region and ultimately in the long term to create a more Sino-centric system that is beneficial to Chinese interests, reducing the overall hegemony of the United States. This process embodied by recent economic and trade announcements at APEC 2014, would return Beijing back to the historic, regional and trading position it held during the Song, Ming and Qing Dynasties.

The arrival of the United States 7th Fleet in the Asia-Pacific and the post-1945 regional order it enforces, including the current maritime borders containing so many disputes, is by comparison a relatively recent development, given this historical perception. This ‘Middle Kingdom’ mentality is very much evident in Chinese strategy in the South China Sea. China is not a rising power but a returning one with both increasing economic interests and maritime capability. The persistence of claims by People’s Republic of China of a ‘nine dash line‘, or as noted in September 2013, the addition of a tenth dash in the South China Sea, denotes an area within the strategic waterways of the Pacific, in which China was the central economic actor during it’s 4,000 year history.

In 2012, the Communist Party reclassified the South China Sea as a “core national interest”, placing it alongside such sensitive areas as Taiwan and Tibet however unlike in those areas, China’s has only until recently been able to exert influence, given its increased capabilities. Over the course of 2013-2014, China has increased it’s presence in the Spratly islands via large scale dredging projects constructing artificial islands with harbors and in the case of the Yongshu Reef, a 3,000 meter runway. We are now seeing, for the first time in two centuries an increased and permanent Chinese surveillance and economic presence in the South China Sea.

Thus,we come to China’s intentions. Under Article 57 of the UN Convention under the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Chinese territories in the South China, such as those currently under construction, would be able to declare a 200 nautical mile economic exclusion zone (EEZ), giving Beijing, under this interpretation, a freehand within the region and forcing other actors in the Asia-Pacific including the US Navy to respect these exclusion zones and not operate within them. Combine this trend with the increased maritime traffic within the shipping lanes of the Asia-Pacific since 2008 and China’s intentions are visible. The most recent figures from 2010 highlight that, China exported 31.3 million tons of containerized cargo and imported 12 million tons. With China so reliant on maritime-based trade, Beijing is boosting it’s presence in the South China Sea in order to secure it’s economic interests in a region where for 4,000 years it was a principal actor.

Indeed China seems unlikely to halt this expansion in spite of recent US State Department criticism, Maj. Gen. Luo Yuan of the People’s Liberation Army stated that “China is likely to withstand the international pressure and continue the construction, since it is completely legitimate and justifiable”. This statement visible in the Global Times, a paper notable for it’s nationalism. Thus in the South China Sea, China is indeed playing a dangerous game as some have suggested, but the challenge presented is an economic one and it’s game plan, China as the Middle Kingdom, is visible to those who know China’s 4,000 year history.