The PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympic Games officially began as of last Friday. Previously, the country hosted major events such as the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics and a joint 2002 FIFA World Cup with Japan.

It was on July 6th, 2011, when the city of PyeongChang was announced by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to host the Winter Games. To distinguish the South Korean town from Pyongyang, a capital C was added to PyeongChang, thus rebranded as the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics. Although this is Korea’s first attempt to host the Winter Olympics, the success of previous events, especially the 1988 Summer Olympics, shows potential promise.

South Korea has campaigned on the promise that an Olympic Games in PyeongChang would capture the notions of harmony and unity between the Republic of Korea (or South Korea) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (or North Korea), transcending from the iconic and catastrophic division of Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), which is roughly 80 km (50 miles) away from PyeongChang. Every effort was made by the Korean administration to conceptualize the revival of the 1988 Summer Olympics where South Korea indoctrinated a message to the global community: from a war-torn devastated nation to one of the most economic and culturally rich states within a half-century. It has been exactly 30 years since South Korea hosted the Olympics, and Koreans are prepared to showcase their miracle once more.

Amid the uncertainty of Kim Jong-un’s nuclear development and President Donald Trump’s “various options,” President Moon Jae-in of South Korea has vowed to thaw this escalating tension by approaching North Korea with peace and diplomacy. While the tension remains at its height, the idea of South Korea thawing tensions with isolated North Korea became crystallized in the course of the Olympics.

In the midst of this transformation, much attention was, and has been, made to foster a sense of North Korea joining the Olympics. Although the prospect of a politicized Olympics is indeed an important discussion, the aspect of independent experience of collective pleasure over the Olympics has been long forgotten. With the introduction of a joint Korean team and a unified flag, the anticipation of the Olympic Games has manifested into a situation of complex international politics, whereby tensions between America, North Korea, and South Korea escalate as they negotiate for their respectable national agendas.

For a more politically neutral perspective on this politically complex Olympics, visitors should be aware that PyeongChang is isolated from the glamorous examples of South Korean development: the city itself is heavily fortified by mountains and is located in a relatively remote region of the country. Unforeseen problems found with some aspects of this unfamiliar city for visitors is that PyeongChang is — aside from the fact that it shares a similar name with North Korea’s capital, Pyongyang — 180 km away from Seoul while the city has undergone a major transformation only within a last half decade just for the Olympics Games.

The South Korean government has invested $13 billion into infrastructures over the years, but the city remains isolated and was not designed to accommodate a vast number of visitors and athletes combined, especially with the fact that the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics will be “the first in Winter Olympic history to hold more than 100 medal events,” according to CNN.

While the government propagated a respectable amount of investment to ensure a success of the Olympic Games, it is undeniably important to confront the fact that the Olympics is being held during the Korean New Year (also known as the Lunar New Year), one of the most significant traditional Korean holidays. The luxuriant congression to this significance is the fact that millions of Koreans will make their way home to celebrate with their family members, inevitably causing drastic traffic congestion with train tickets being extremely competitive. Attempts are possible, but the language barrier, especially on Korean websites, offers a little or limited subversive solution.

From a cybersecurity perspective, South Korea is one of the few nations where a single internet browser, Internet Explorer (I.E.), dominates the market. The government remains confident from the enhanced respectability usage of the outdated ActiveX, a web browser plug-in created by Microsoft in 1996 as a way to manage cyber control. It has been reported that three-quarters of all South Koreans were using I.E. as of 2013, while the dependency on ActiveX was further exacerbated as cyber security became a major concern.

Rather than providing easier solutions for online transactions, which might provide smoother accessibility for non-Koreans, the installation of ActiveX has caused a widespread frustration to both Koreans and non-Koreans alike, including multiple security breaches. Fortunately, the government has attempted, and encouraged, public organizations to withdraw ActiveX for the past several years, but Korea’s dependency on this plug-in remains a problem.

In contrast to many other locations, the South Korean government did not favour allowing Google Map features in the Republic of Korea. The government argued against the use of Google Maps, and favoured of protecting sensitive information, such as visibility of key military facilities, over technological innovations, as stated by Google. For South Korea, the major materialistic concern over accessibility was providing adequate mapping data to foreign countries, especially to South Korea’s northern neighbour. South Korean civic groups have also argued that Google remains unwilling to comply with the nation’s tax regulations, as Google declined to build a facility in Korea to house its servers—something which critics have derided as a tax avoision scheme.

It might be added that there is, in addition to the main political dissent over North Koreans participating in the Olympics, little support from South Korean multinational conglomerates for the Olympics. With former President Park Geun-hye jailed, top leaders of the country’s largest “chaebols” (conglomerates) were also questioned and even jailed, like Samsung Group heir Jay Y. Lee (who was recently freed), over financial support and bribes in both politics and national events.

Under the President Moon administration, investigations were made against major South Korean conglomerates, which eventually crippled the Federation of Korean Industries (FKI). This was a network of conglomerates working within the system for formulated aims of cooperation for national interests, in connection with the expansion of their interests as well. This very opportunity was shattered when the country was subjected to a political crisis of Moon restituting progressive and economic liberal values, with the effective dismantling of multinational conglomerates and the repressive nature of the Moon policies against conglomerates fueled uncertain subjects to Korean conglomerates.

Rattled by the need of financial support from conglomerates, the Moon administration and Lee Nak-yeon, Prime Minister of South Korea, held a meeting with the FKI and its former members, including Samsung Group, Hyundai Group, POSCO Group, LG Corporation and SK Group, to request for financial support and sponsorship for the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics. Although there is support, Samsung providing 10% of entire sponsorship, for example, there is no massive enthusiasm for sponsorship which remains relatively dangerous, with serious penalties by way of political reprisals as exemplified by the Moon administration.

The diverging cultures and aspects of Olympics values have brought a unique development on the Korean peninsula. In some ways more worrying from the point of view of Americans is the development of South Korea weakening the United Nations sanctions on North Korea. To a certain extent, this peaceful approach by South Korea is an indicative of a new approach to stimulate peace and unity, an alternative to a resentment of extreme “possibilities.”

Yet, while there is a wide range of hope of one form or another over the celebration of achievements and unity during the Olympics, there is a more widespread form of uncertainty and division in both South Korea and worldwide over North Korea. The reason for this may vary, but one important factor has to do with the Moon administration’s relative soft approach to North Korea with nothing in return.

But fear is contagious, and it should be treated with care. Fear of the impact of war, especially, echoes in memories of many Koreans. For within a few past months a series of tensions erupted and snowballed, and the very existence of peace on the Korean peninsula was under question. Nevertheless, if one accepts that North Korea returns peaceful and docile into those aspects of the past, it should be possible to illustrate in rational conclusion, within given a turbulent history of North Korean provocations, that North Korea remains capable of endangering regional and international peace and security once more.

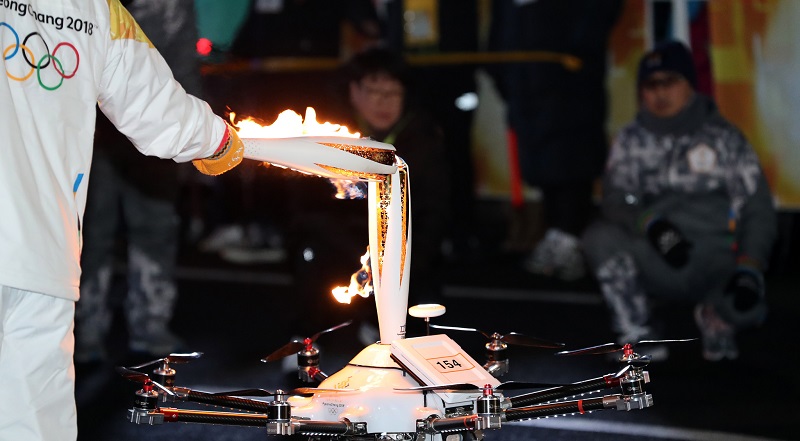

Photo: 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympic Games’ Torch Relay in Seoul, by Jeon Han via Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. Public Domain.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors’ and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.