The end of the Second World War and the Allied occupation of Japan has had a lasting impact on Japan’s views of military conflicts. Under General Douglas McArthur of the United States Army, who served as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, the Allied authorities in Japan were committed to the demilitarisation and democratisation of Japan. Japan, under pressure from the United States, publicly renounced the use of force as a means of settling international disputes, banned military leaders from having influence over politics, and became a pacifist nation, a concept which has been accepted by much of the Japanese public and many politicians.

Japan created a new military, the Self-Defence Force (SDF), which would guarantee Japan’s sovereignty, but would not have the right to perform military operations outside Japan. The SDF has evolved to be a type of safety net, active only when the Japanese Coast Guard or police fail to control certain situations.

In recent years, however, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party has voiced concerns that gaining approval for the use of SDF would be too slow during times of crisis and could undermine Japanese security. Japan’s current Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has recently shown greater interest in restructuring the Japan Self-Defense Force. Abe advocates a new ‘active pacifism’ strategy which increases the role and capability of Japan’s SDF. Under Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, the SDF can only guarantee the independence and security of Japan using a minimum amount of force. The article states that “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes”.

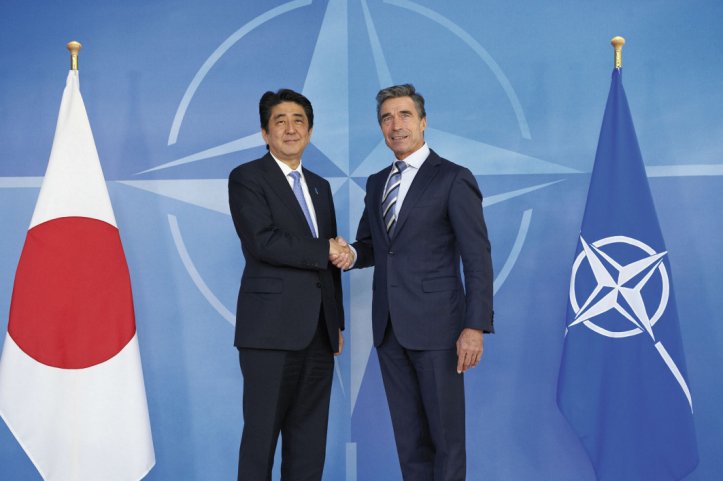

This implies that Japan cannot legally support an ally militarily, which according to Abe is a hindrance in the Asian regional security system. Shinzo Abe used a 6 May speech to the North Atlantic Council to expand and explain this point simply. “Under the current interpretation of the constitution, even if a US Aegis-equipped vessel on the high seas near Japan on guard against a possible missile launch suffers an armed attack, Japan’s Self-Defense Forces are unable to defend it,” Abe said in Brussels. Even though Japan is a close ally to the US, it cannot legally come to the aid of another NATO member. The mutual protection which the US-Japan alliance is supposed to guarantee is purely unilateral—Japan cannot truly help the US. According to Abe, this would not be an “appropriate response” to a crisis. For this reason Abe has been pressing for a reinterpretation of Article 9 of the constitution to allow for collective self-defence, which would legitimate a more active role for the SDF in Northeast Asia’s regional security system.

In December 2013, Abe created the National Security Council (NSC) which is supported by his own secretariat and aims to centralise and hasten national security policy and implementation within the executive branch. Soon after its creation, the NSC supplied a South Korean unit on a UN mission near Bor, South Sudan with 10,000 units of ammunition. Abe has also created Japan’s first National Security Strategy (NSS), which focuses on a shift in the balance of power in the Asia-Pacific region and a risk of ‘grey zones’ which could escalate to bigger conflicts. In his article for IHS Jane, a Defense and Security Intelligence publication, James Hardy wrote that “rather than centralise policy, as the NSC does, at the practical level the NSS seeks to standardise or join up security policy across all government agencies and departments”. Hardy outlines how this could work in practice, stating that the NSS calls for the “strategic utilisation of overseas development aid (ODA)” and overturning the self-imposed military export ban.

Abe recently passed new guidelines loosening the 1967 ‘three principles’ export restrictions. These included selling military ODA to communist countries, nations with UN sanctions, and countries involved in interstate conflicts. The NSS has abolished the first two principles though it retains the third. The NSS also states that these changes will be limited to cases which promote peace and international cooperation. “The Defense Ministry and the Self-Defense Forces will make more active contributions to peace and international security under the three principles on defense transfers,” Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera said in a statement on April 1st 2014, “we will more actively cooperate on defense equipment and technology with our ally the U.S. and other countries to maintain regional peace and stability.” Abe is actively supporting the first sale under this system: the purchase by the Indian Navy of ShinMaywa US-2i amphibious search-and-rescue aircraft. as well as building on joint military development agreements signed with Australia, France, and the UK.

In part two, Piotr Zulauf will further discuss changes made to Japan’s strategic stance by Prime Minister Abe and how those changes will affect neighbouring states.