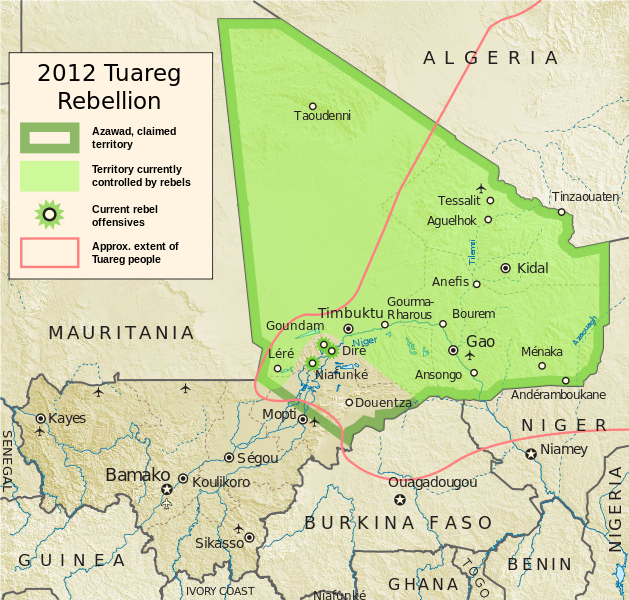

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”320″ imgsrc=” http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-wI8OvvtSDac/T34HRBHYZPI/AAAAAAAABCU/d07QZmGk_PU/s1600/tuareg+rebellion+map.png” captiontext=”Mali’s de facto partition.”]

By Nicholas Bishop

In the latest news to come out of Mali, two rebel groups, Ansar Dine and the National Movement for the Liberation of the Azawad (NMLA) have joined forces to fight for the independence of the north of the country and the creation of an Islamic state. The two groups completed their takeover of northern Mali in late March after seizing Timbuktu, the last major town still under government control and declaring de facto independence for the state of “Azawad” on April 6. Until recently, the NMLA, a secular movement led by Tuareg separatists had been in opposition to the fundamentalist Islamic group, Ansar Dine’s desire to impose Islamic Shariah law and create a distinct homeland for the Tuareg, leading to turf wars between the armed camps. Previously, independence seeking Tuareg guerrillas have led rebellions across the Sahara from the late 1950’s through to the 1990’s, and again in Niger in 2007. Northern Mali is a vast expanse of arid desert country roughly equal in size to France.

The coup d’état in the Malian capital of Bamako on March 21 deposed democratically elected President Amadou Toumani Touré after 12 years in power and only one month in advance of new elections to replace the outgoing leader. Allegations of government corruption and an economy deflated by sagging tourism numbers triggered several weeks of protests by both civilians and soldiers, who had demanded more arms and better resources to halt the northern rebellion of the nomadic Tuareg. Marking a turning point in the civil war, the rebels’ position was bolstered after an influx of Tuareg troops brought back arms and vehicles from Libya where they had been fighting as mercenaries with pro-Qaddafi forces.

Often cited as a democratic model in the region, Mali had been a priority country for Official Development Assistance (ODA) from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) receiving over CAD $100 million in annual aid. On March 24, the Canadian government immediately condemned the coup and suspended all aid programmes. Foreign Affairs Minister Baird responded to the situation by saying, “We call on those behind this coup to immediately withdraw so that constitutional order, peace and stability may be restored.”

Bucking the trend towards democracy in most of the rest of Africa, including neighbouring Senegal which recently saw its fifth consecutive democratic transition of power, Mali’s recent struggles are a throwback to a more violent, unstable past. Despite relatively low casualty figures throughout the course of the rebellion and resulting coup, international aid organizations believe that more than 200,000 people have been displaced as a result of the conflict and have warned of a humanitarian crisis exacerbated by a regional drought.

Following the overthrow of the government in March, ECOWAS, the West African Economic Trading Bloc of 16 nations immediately imposed sanctions and closed their borders to all non-humanitarian trade with Mali. The Canadian government supported the moves with Minister Baird stating that, “Canada stands ready to work with the Economic Community of West African States and other partners on solutions to this crisis, and to help a democratic Mali build a better, brighter future for all Malians.” The restrictions were later lifted in April after a negotiated settlement was reached with coup leader Captain Amadou Sanogo. The Captain issued a new 69 point Constitution and said he would turn power over to a democratic government after an undefined period of transitionary rule. He eventually stepped aside after only three weeks in favour of Mali’s speaker of parliament, Dioncounda Traoré, for a 40-day interim period. However, real power continues to be maintained in the hands of the military junta, who have proclaimed a desire to retake the northern portion of the country through the creation of a more powerful army. Most recently on May 22, Mr Traoré was assaulted by protesters at his office in Bamako after a deal brokered by ECOWAS that would have seen him stay on as president for one year drew harsh criticism. As with Mr Traoré, the health of democratic governance in Mali hangs in the balance.

In light of Mali’s de facto partition along the north-south axis several unanswered questions remain. Namely, can the rebel groups in the north maintain their proclaimed independence against possible attack from 3000 ECOWAS troops on standby in the region, or the eventual power of the reconstituted Malian army, which currently counts 7000 members? Expansion of any conflict especially on a cross border scale would severely cripple Mali’s chances of returning to healthy democracy. Secondly, will Mali’s current dalliance with military rule last? As one possible sign of things to come Captain Sanogo appearing on Malian television told his audience that the military junta “is not going anywhere; when a group of soldiers takes power, nobody can sideline them, and that’s no joke.” Concrete, coherent reforms aimed at improving economic performance and supporting the livelihoods of average Malians must be central to any new government— this includes a move back into democracy, not away from it.