Last week, four Russian fighter jets sliced through international airspace over the Baltic Sea, darting towards Sweden with their transponders turned off. Unable to detect or be detected by other planes, the jets hugged Sweden’s airspace over Gotland and the Danish island of Bornland before turning back towards Russia. One could be forgiven for thinking this is déjà vu.

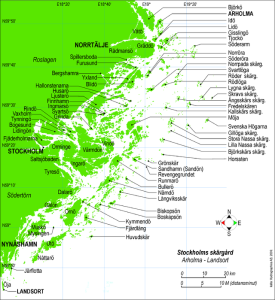

In September 2014, two Russian jets flew into Swedish airspace near Öland, in what former Foreign Minister Carl Bildt called the worst violation of Swedish airspace in over a decade. In 2013, Russia launched a simulated bombing raid comprised of six military aircraft pushing up against Sweden’s airspace near Stockholm, including two nuclear-capable bombers. And then, of course, there was the infamous submarine debacle in October. The Swedish military now estimates that up to four Russian submarines were lurking among the Stockholm archipelago’s 30,000 islands, escaping detection from Sweden’s unprepared navy.

Sweden’s intelligence service, Säpo, asserted this month that one in three Russian diplomats are spies. The agency’s chief, Wilhelm Unge, interprets this activity as “preparation for military operations against Sweden.”

Taken together, the incidents demonstrate an unmistakable signal from Russia, at once a threat and a test. Sweden remains officially non-aligned, the only country to do so in the region other than Finland. All other Nordic countries (Denmark, Iceland, Norway) and the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) are members of NATO. With this fact, the intent behind Russia’s actions comes into clearer focus.

One of the likely motivations behind Russia’s aggression is to highlight Sweden’s frail military defences. In the hunt for Russia’s subs, many of the Swedish Navy’s boats were inflatable, and there were no anti-submarine helicopters to assist in the mission – except for those tucked away in a museum in southern Sweden. Stockholm recently announced a $696 million spending hike for its navy from 2016–2020, with an emphasis on improving its ability to locate submarines in Swedish waters.

The Air Force hasn’t fared much better: during Russia’s 2013 bombing simulation, Swedish jets were caught so off guard that they were unable to respond, calling in help from their Danish neighbours to shadow the Russian planes. Though Swedish planes were able to scramble in response to the latest aerial incursion, public trust in the military is low. According to an October poll, only 6% of Swedes have faith in their country’s ability to defend itself.

The main message behind Russia’s bellicosity, regards Sweden’s relationship with NATO. Though Sweden is not a member state, it is a long-standing ally that cooperates extensively with the Alliance. It is participating along with Finland in NATO missions in Afghanistan and Kosovo. It took part in the Libya intervention of 2011, and it is a member of over 150 NATO committees. Most importantly, Sweden and NATO signed a Host Nation Support (HNS) agreement in September, allowing the Alliance to use Swedish territory, airspace, and waters for operational purposes—with the prior consent of the Swedish government. NATO recognizes Sweden’s “long-standing policy of military non-alignment,” while also regarding it as an “effective” partner who shares “key values.”

Sweden is a key geostrategic player for both NATO and Russia. It also plays a vital role in the security of the Baltic States, all of whom want both Sweden and Finland to join them in NATO. Both countries have a tacit agreement that, if they were ever to join the Alliance, they would do so together. But in both countries, internal dynamics, external pressure, and history all have a great bearing on any such decision.

Public opinion in Sweden has long opposed joining NATO. However, a poll taken after the submarine fiasco indicated that, for the first time, more Swedes supported NATO membership than opposed it. Since the New Year, some polls have shown modest support for NATO, while others demonstrate that a plurality of Swedes may support membership.

Whichever numbers are trusted, it is clear that the membership issue is no longer cut-and-dried. Newly-minted opposition leader Anna Kinberg Batra, head of the Moderate Party, has called for a “study on the concrete preconditions for Swedish membership of NATO.” For his part, Prime Minister Stefan Löfven of the Social Democrats ruled out NATO membership in his opening speech to Parliament last fall. Members of his Administration have repeatedly downplayed the threat posed by Russia, and Foreign Minister Margot Wallström dismissed the October poll showing heightened NATO support as the result of “exaggerated and almost war headlines” following the submarine incident.

But if the timing of its aggressions is any indication, Russia has been doing its best to eliminate any inclination towards Brussels among Swedes. It is likely no coincidence that Russia sent a jet into Swedish airspace the same month that the latter finalized its HNS agreement with NATO. Along with the announcement of $696 million for its Navy, Sweden’s military also unveiled this month that it will station 150 troops on Gotland for the first time in over a decade. Thus, when four supersonic warning signals from Russia arrived at the island’s doorstep just weeks later, it should have come as little surprise.

Stockholm finalized defence agreements with both Denmark and Finland in the past two months, but neither of these is likely to alter the balance of power with Russia.

Given Russia’s intimidation tactics, some argue that it may make sense for Sweden to remain officially non-aligned; its security is likely assured by both its EU and NATO partners in the event of a Russian attack, and NATO may have little to gain from the formality of Swedish membership. A Ministry of Defence report from October stressed that Sweden places great value on its “sovereignty and national freedom of action,” including its decision to remain officially non-aligned. However, the same study suggested that, at this point, the country is so integrated with NATO and its members that it “cannot really avoid being identified with the Alliance – yet without enjoying either the effects of cooperation or the joint protection that would be offered by membership.”

In calling for the study on potential NATO membership, Ms. Kinberg Batra declared that “it is time now” to take that step. While Löfven’s government would disagree with her assessment, it is clear that this national conversation is not yet settled. Whatever the outcome, Russia will be listening.