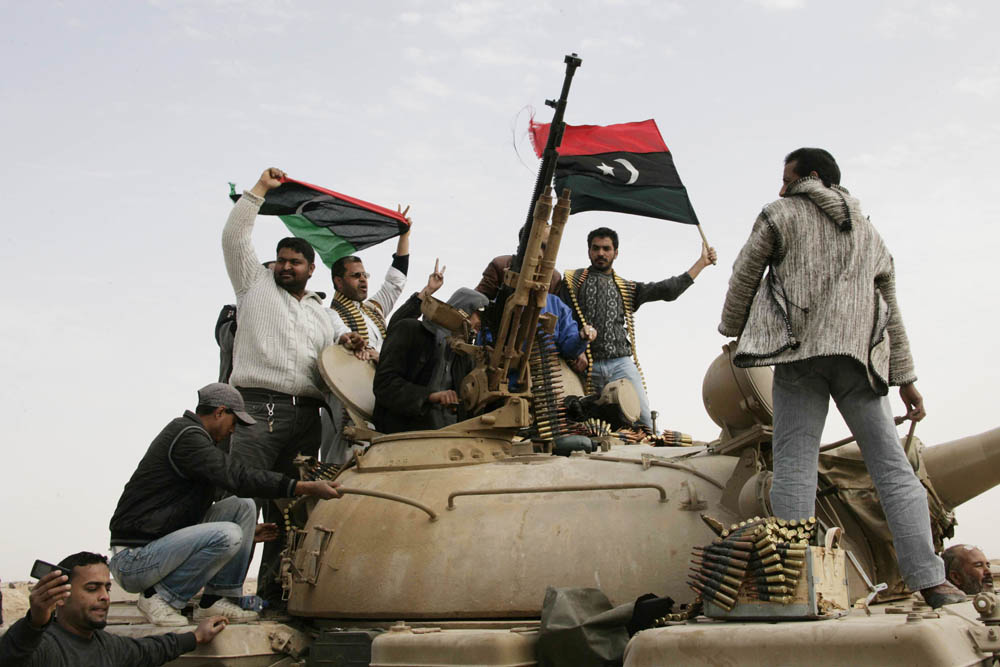

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/libyan-rebels.jpg” captiontext=”Militias have operated with impunity as Libyan authorities have failed to control them.”]

On February 17, 2011, Libyans began an uprising that eventually led to the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi following his 41 years in power. However, in the three years since, the country remains insecure and Libyans find themselves living in an increasingly repressive human rights environment.

Militias, which took up arms to overthrow Gaddafi, have refused to disarm since 2011 resulting in a multitude of security problems. Libya faces a lack of border patrol, much tribal infighting, weapons and drug trafficking. Militias have acted with complete impunity as state authorities have so far proven unable to control them.

An August 2013 report by Human Rights Watch said that 51 people had been killed in political assassinations in the cities of Benghazi and Derna as police, military officials, lawyers, judges and political figures have found themselves vulnerable to militias.

Armed groups control large areas of the country including some of Libya’s oil terminals. Seizures of the terminals have resulted in Libya’s exporting as little as 200,000 barrels of oil per day which is a significant decline from up to 1.4 million barrels per day following the revolution.

Libyan authorities ‘contract’ militias which operate parallel to the state security forces to help impose order. Such efforts have been criticized since they illustrate the government’s inability to establish security forces capable of disarming militias and securing the country.

The diplomatic missions of countries such as Egypt, France, UAE and Yemen, have experienced attacks, in addition to the September 2012 attack on the US diplomatic mission, which resulted in the death of Ambassador Christopher Stevens.

60,000 Libyans accused of close ties to the Gaddafi regime found themselves internally displaced following the revolution. This figure includes 35,000 in Tawergha accused of siding with Gaddafi during the revolution. Tawergha have found themselves under attack in recent years with an estimated 1300 detained, missing or dead.

At least 31 people were killed and 235 wounded during peaceful protests in Libya in November 2013. The protesters, who called for the disarmament of Libya’s militias were attacked by militia that opened fire with heavy machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades.

Since 2011, Libya has experienced a lack of freedom of expression including attacks against journalists. A Gaddafi-era law titled ‘Law Number 5’ was recently amended that outlaws insults to the Libyan state, its emblem or flag or to the 17 February Revolution. Several Libyans have been charged for insulting the revolution and other repressive measures have been introduced to crack down on anyone accused of doing so. One of these measures is directed at Libyan expats and allows for the withdrawing of their scholarships, salaries and bonuses if they are found to engage in activities hostile to the 17 February Revolution. Law Number 5 also undermines the Constitutional Declaration following the 2011 revolution which vowed to guarantee fundamental freedoms. These efforts by the Libyan state run in stark contrast to the spirit of the 17 February Revolution which sought greater freedoms for the Libyan people.

Journalists have operated in conditions progressively hostile to their work and have been subject to violence. Two journalists have recently been assassinated and local TV channels have been threatened and attacked. There have also been three cases of abducted journalists. In the 2014 Reporters Without Borders index, Libya is ranked 137th out of 180 countries in terms of press freedoms.

In January 2014, the Libyan human rights group, The National Council for Civil Liberties and Human Rights released a scathing critique of the government’s inability to secure the country and rein in armed militias. In addition to human rights violations in schools, hospitals, against minorities and the disabled, it reported torture, extra judicial executions and detentions in 52 prisons it inspected in the second half of 2013.

Human Rights Watch has also expressed concern over the treatment of Saif al-Islam Gaddafi and other former regime officials who have been held in detention without due process. They have been held without access to lawyers, without the opportunity to review evidence submitted against them, nor were fully aware of the charges against them. Gaddafi remains in the custody of Libyan authorities even though the International Criminal Court announced Libya was obliged under international law to hand him over to the court in The Hague. Despite the ICC’s ruling back in May 2013, Libyan authorities continue to insist on trying Gaddafi. The case of Gaddafi illustrates that Libyan authorities are not only unwilling to uphold basic human rights such as the right to a fair trial, but are also unwilling to abide by international law in the wake of the ICC’s ruling.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Saif-al-Islam-Gaddafi-007.jpg” captiontext=”Saif al-Islam Gaddafi has been held without due process since 2011″]

The absence of due process has further been experienced by a total of 8000 detainees held since 2011, 5000 of whom have been held by militias. They have been held without access to legal counsel nor have been granted rights for judicial review.

To make matters worse, ruling authorities have failed to guarantee the human rights promises they made following Gaddafi’s ouster, creating a climate of both physical and political insecurity. Overall, the incompetence of Libya’s ruling authorities, combined with the brazen behaviour of armed militias has created massive insecurity and instability in the country.