The first part of this series discussed the evolution of counterinsurgency strategy in the American military. This instalment will analyze the application of these tactics in America’s two most recent COIN conflicts, Iraq and Afghanistan.

The first year of the invasion of Iraq was crippled by an insistence on low troop levels and high reliance on firepower by high-ranking bureaucrats in the American Department of Defense. After it was clear that this technology-based strategy was not effective against Iraqi insurgents, the American military shifted towards a counterinsurgency-based strategy, resulting in the creation of a new COIN field manual by the U.S. Army and Marine Corps, under the guidance of General David Petraeus in 2007. This COIN doctrine was later applied in Afghanistan to varied success. There of course have been isolated victories of counterinsurgency, but the overarching military culture and widespread mismanagement of COIN has resulted in a structural divide.

The purpose of a military force is historically combative; by asking for counterinsurgency, we are asking for an expansion of mandate and capacity.

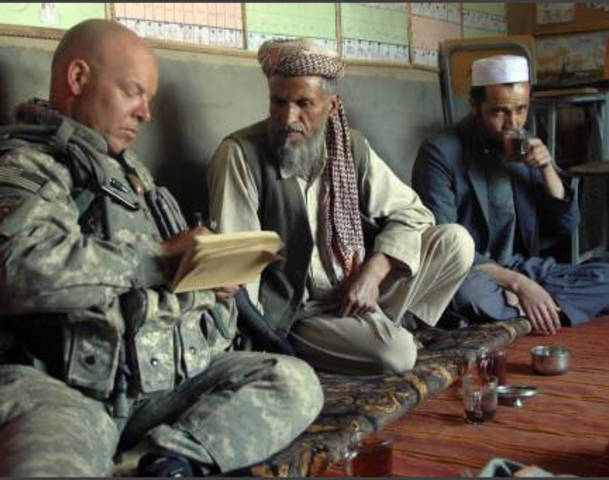

In Afghanistan, as in Vietnam, there was a major disconnect between theory and application. Even though the Counterinsurgency Field Manual says explicitly that a successful counterinsurgency operation must focus on protecting civilians rather than killing insurgents, the use of minimum force, and the exposure to greater risk on the part of the counterinsurgents, the approach was far from embraced in Afghanistan. The new COIN manual remains intensely controversial and. in fact, it is not even widely distributed amongst American military commanders. Critics of the new manual believe that the doctrine is reminiscent of state-building practices, not military tactics, and others bemoan COIN as a euphemism for neo-imperialist tendencies. On the surface, the Counterinsurgency Field Manual seems to articulate some lessons learned from Vietnam in an effort to refine counterinsurgency tactics, but the usefulness of this new COIN doctrine is in doubt since it has not been faithfully or successfully applied in Afghanistan.

In practice, the American counterinsurgency in Afghanistan has been characterized by a high number of civilian casualties, the isolation of troops from the local populace, and a heavy reliance on air support. As in Vietnam, military tactics have served to exacerbate the local population’s grievances against the counterinsurgents rather than the insurgents themselves. Soldiers have often been unable to differentiate between insurgent and civilian; this, along with the indiscriminate use of air power, has led to massive civilian casualties and turned the Afghan population against the foreign presence. And so despite their earlier experiences, the COIN offensive in Afghanistan is eerily reminiscent of the experiences in Vietnam. Both counterinsurgencies are marked by a military culture that refuses to let go of the high-intensity, short-term war, and adapt to the low-intensity, locally integrated conflicts that characterize contemporary warfare.

It may not be surprising that the American military has tended to fall back on conventional warfare tactics given that state-building requires a political element that the military is often not equipped to provide. This often manifests itself in the miscomprehension of local power relationships or the nuances of ethnic, societal, or religious divisions. The purpose of a military force is historically combative; by asking for counterinsurgency, we are asking for an expansion of mandate and capacity that simply does not currently exist within most military institutions. Until the gap between intellectual theory and practical capacity is bridged, counterinsurgency tactics will continue to be misapplied and misunderstood.

The American experiences in Vietnam and Afghanistan show a deep cleavage between counterinsurgency in theory and in practice. However, despite the general support for counterinsurgency as a tactic, there has been an institutional roadblock in the culture and administration of the American military. In Vietnam, as in Iraq and Afghanistan, the focus of the American military was on the defeat of the enemy, and not the security of the civilian populace. And indeed, at its heart, COIN doctrine is somewhat guilty of one of its major criticisms; that it tends towards state-building practice rather than just a military operation. Yet that is precisely the point, and the failure to recognize and operationalize this “on the ground” is perhaps the reason that the approach has not been more effective. Counterinsurgency requires the mobilization of the military, but also civilian cooperation and political reform; it is not just a military tactic but also a political doctrine.