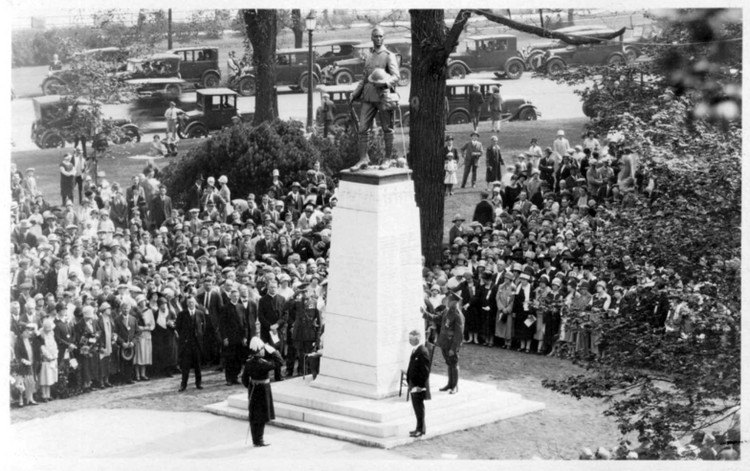

For the past two weeks, Remembrance Day ceremonies across Canada and the world have marked the beginning of what was, at the time, the greatest conflict in global history: the First World War. From London to Paris, politicians, diplomats, and veterans have converged upon sacred sites such as the National War Memorial in Ottawa and the Tower of London to lay wreathes, deliver speeches, and pay tribute to the sacrifices of the war dead.

Repeatedly, we are told, the First World War was fought for high-minded ideals, for democracy, freedom, and the rights of small nations. The war dead – whether British, Canadian, or French – made the ultimate sacrifice in service of these liberal values.

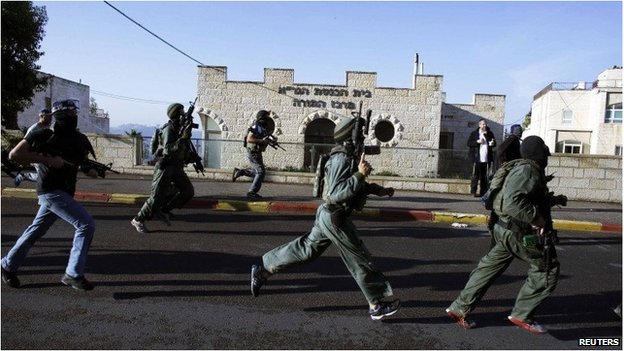

In Britain, Prime Minister David Cameron has eulogized the war as the defence of “British values”, while in Canada Prime Minister Stephen Harper has spoken of the war dead as the men “who paid for our freedom with their lives”. In Canada, in particular, the sombre and poignant tone of these ceremonies has been heightened by the recent deaths of Warrant Officer Patrice Vincent and Corporal Nathan Cirillo, killed in separate but ideologically motivated and linked terrorist attacks at the end of October in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu and Ottawa.

Remembering the First World War as an almost apocalyptic struggle between the forces of good and evil, between democracy and autocracy, fits neatly into the more modern, post-Second World War and Cold War discourse about righteous wars against totalitarian ideologues. How else, one might ask, can we come to terms with and accept the long list of deaths and casualties wrought by the Great War, a list that is higher than that produced by the ‘total’ warfare of the Second World War?

Yet the First World War, in truth, had little to do with preserving the rights and freedoms of either North America or Europe. From the British standpoint, the war was fought for pragmatic and logical reasons. Britain had to prevent Germany from gaining control of northern Europe and the vital coastal ports of Belgium and the Netherlands. Moreover, German domination of the high seas posed a legitimate and potentially devastating threat to imperial commerce, while German political and economic overtures in the Arabian Gulf and Middle East challenged Britain’s traditional sphere of influence, which was centred on the route to India.

By the time of the First World War, Germany was ascending rapidly as a world power. It was economically vibrant, scientifically advanced, and in possession of a well-trained, modern land army as well as a burgeoning and well-equipped navy.

Russia, too, was on the rise. On the eve of war, Tsarist Russia was the world’s fourth-largest economy. Its land army was enormous and with the modernization of its transportation infrastructure, especially its railways, Russian territorial ambitions were no longer shackled by how far the army could march across its seemingly never-ending geography.

Modern scholarship on the war’s manifold causes – and there were many – have rightly pointed out that the First World War was, in reality, a conflict between empires: Germany and Russia rising, France and Britain trying desperately to hang on to their privileged positions.

The war, simply put, was about power politics and preserving the status quo in Europe. Britain, France, and Russia had a mutual interest in containing the German Empire, which had long hoped to overturn Britain’s world dominance. Of course, other issues also led the great powers to war. The gamble, for instance, made by all sides, that a war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia would be short and isolated.

But the argument that Germany’s violation of Belgian neutrality, its disregard of international law, and Britain’s need to safeguard democracy worldwide underpinned the British Empire’s involvement in the war was as flimsy one hundred years ago as it is today. This line of thinking is rooted in wartime propaganda, not historical fact. It stems from an easily understandable desire to lend meaning and importance to death, as we do today with the memories of Officer Vincent and Corporal Cirillo.

By no means does this article suggest that Britain, Canada, or France, to name but a few countries forever touched by the First World War, should not commemorate the lives of its war dead. But we should be honest with ourselves and faithful to the history of that catastrophic conflict.