The fall of Muammar Gadhafi instilled a new sense of hope in the Libyan people, who had suffered greatly under his 40-year dictatorship. Today, that jubilation has been replaced by a fear of instability, caused by unaccountable militias, a weak and stagnant economy, and a state government that is almost completely absent. Moreover, the consequences of Libya’s instability have been felt across the region.

Issues of accountability, particularly in public security, emerged shortly after the rebel victory. Within weeks, the people of Libya began to demand a transition towards democracy, away from the rule of the rebel political leadership, the National Transitional Council (NTC). The NTC, acceding to these wishes, ordered the creation of the General National Congress (GNC), an elected legislative body that would also choose the members of a constituent assembly, which in turn would write a new constitution. Elections for the GNC were held in July 2012 under an extremely complicated electoral framework that mixed proportional representation and first-past-the-post single-member districts, which would only be open to independent candidates. Members of the Gadhafi regime were barred from running, a contentious point for many former supporters of the old regime.

The elections went fairly smoothly, to the surprise of most outsiders, who were worried about Libya’s lack of pre-existing institutions and fragmented security environment. However, the GNC has proved largely incapable of governing. Internal division prevented the wide array of tribal leaders, Islamists, regionalists, liberals and others from agreeing on the basic structure of a new Libya, culminating in a recent decision to replace a planned GNC-appointed constituent assembly with a directly elected one. The government has been unable to revive the pre-war economy, with oil production still below capacity. The government has even been incapable of protecting the country, or even its own members, from militia violence, with effectively no national army or police to speak of.

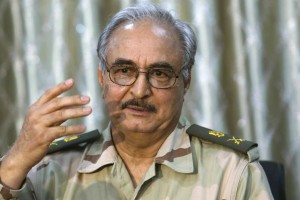

This rampant violence is the major issue holding back post-war Libya. After the war, the militia forces that formed to overthrow the government did not disband. Rather, the young men, for whom other opportunities were absent in the devastated economy, stayed in their militia brigades and held on to their arms. These groups began to act as security forces in the territories they occupied, doing the regular job of the police, courts and army. Traditional methods of disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) were impossible without an armed force to maintain security and enforce the program in the absence of the militias. Instead, militia groups began to coalesce into organizations, such as the Supreme Security Committee (SSC) and Libya Shield, which provide a degree of respectability and centralization. The leaders of these organizations have become extremely powerful unelected political players; General Khalifa Haftar is one of these men. Meanwhile, Islamist militias have continued to organize, with links to terrorist groups, while other former fighters have simply joined the criminal underworld.

At their most basic level though, the militia fighters are untrained and prone to abuses of power, criminality and clashes with other militias over personal, communal and ideological disputes. Enforcing laws, particularly when militia members violate them, has become impossible. Throughout Libya, law has increasingly become a matter of ‘might makes right’, with most of the country plauged with discord. Even the country’s oil exports are vulnerable to a militia veto: recently, oil exports were interrupted by militias demanding a greater share of the profits for their region, and the government threatened to bomb rogue tankers seeking to make a quick profit off stolen Libyan oil.

This unrest has spread far beyond Libya, with consequences throughout West and Central Africa. The first country to feel the consequences was Mali. A large number of Tuaregs, a Saharan people who are the majority in Mali’s vast northern regions, served as mercenaries on Gadhafi’s side. When he lost the war, these mercenaries returned to Mali with arms and money, reigniting an intermittent conflict for Tuareg independence. With the aid of al-Qaeda-inspired Islamists, the Tuareg rebels soon defeated a poorly prepared Malian army, leading to a coup against Mali’s longstanding democratic government. The Islamists soon pushed out the Tuareg rebels and enforced harsh Islamic law in the north. This inspired a joint French intervention, which stabilized the country.

Islamist violence at the hands of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Boko Haram in Nigeria and other groups throughout the Sahel and Sahara regions are linked directly to Libya, with mercenaries and weapons flowing out of the country into the hands of warlords and terrorists. The Central African Republic is the latest country to erupt with sectarianism and bloodshed, leading to a warning from UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon that it could be the site of a Rwanda-like genocide. Meanwhile, Libya seems to be collapsing back into a state of civil war, with militias supporting General Haftar and Islamists clashing, while the government remains all but absent.”

NATO and the West, which played a major role in overthrowing Gadhafi, have both a responsibility and an interest in doing whatever possible to ensure that Libya regains stability and can become a country truly ruled by its people. The West should refuse to work with groups that oppose the GNC, while continuing to finance and train the national army and support the central government. At the same time, accepting and regularizing a certain diffusion of responsibility for security to well-organized and disciplined militias may be necessary and even helpful. Efforts to contain the spread of weapons and terrorist cells is also extremely important, although the West should be careful with its methods to avoid alienating populations through blunt tactics like drone strikes. A Libya that collapses or falls into dictatorship would be disastrous, while a stable one would be an excellent example for the region.