The natural gas portfolio of the new European Commission (EC) seeks to ensure security of supply throughout Europe. Simultaneously, it has to determine a role for natural gas towards the envisioned carbon-neutral EU economy of 2050.

The EU was first compelled to advance the supply-security aspect of natural gas after the 2006 and 2009 interruptions of Russian flows through Ukraine. In the years following, the EU strengthened its common gas market by increasing infrastructure permitting gas to flow in both directions, by diversifying its suppliers, by introducing the principle of solidarity, whereby member-states must guarantee gas provision to one another in event of supply cuts, and by establishing competitive pricing mechanisms via gas trading hubs.

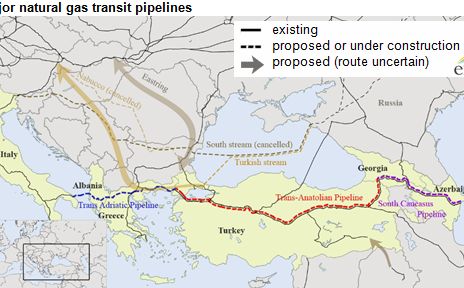

It was along these lines that the hearing of the newly nominated Energy Commissioner, Kadri Simson, unfolded last month in the European Parliament’s Committee on Industry, Research and Energy. Simson stated her intention to ensure EU-wide energy security by accessing different gas sources, including liquefied natural gas (LNG). In this latter connection, she highlighted the successful cooperation with the United States. Thus, she invoked the example of Poland, which benefits from the already commissioned Świnoujście LNG terminal, as well as from the proposed bidirectional Gas Interconnection Poland-Lithuania and the proposed Baltic Pipe from Norway. All these efforts support its policy goal to minimize dependence on Russian gas imports. Simson concluded that “this is a situation which many member countries are aiming for”, referring to the goal set by the previous Commission, that each country in Central and Eastern Europe and Southeastern Europe should be supplied by at least three gas sources, in order to escape manipulation by a single dominant supplier.

Simson, the former Estonian Minister of Economic Affairs and Infrastructure and leader of the Estonian NATO Parliamentary Assembly Delegation, will have the further task of determining the role of natural gas in Europe’s energy transition. Natural gas is an affordable fuel with lower life-cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than oil and coal. It represents about one quarter of the EU’s primary energy consumption, largely covering the heating needs of industries and households. The incoming EC President Ursula von der Leyen wrote in her mission letter to Simson, that the latter would be tasked with providing a clear decarbonization trajectory for gas. This desideratum conforms with the EU’s Paris Agreement commitments, which led to the EC’s long-term strategy for a carbon-neutral economy by 2050.

The emerging concept of gas sector decarbonization forms part of von der Leyen’s “European Green Deal” that EC Vice-President Frans Timmermans intends to put forward within the EC’s first 100 days of office. This initiative will aim for an ambitious 55 percent CO2 emissions reduction target by 2030, up from the previous goal of 40 percent. It will involve maintaining the use of natural gas in the medium term while coal is phased out. Gas will also serve as a back-up to intermittent renewables (solar and wind) until 2030, when demand for it is expected to stabilize around 400-420 billion cubic metres per year (bcm/y).

Although environmental activists frequently criticize EU funding for gas infrastructure, the EC’s Green Deal is expected to promote its continued use, with adaptations for the transport of low-carbon gases (e.g. biomethane from organic sources, hydrogen from renewable power and hydrogen from natural gas combined with carbon capture technology). Within this framework, the intention is that natural gas demand should decline after 2030.

Endorsing natural gas and LNG investments, Simson also stressed that she supports the “future-proof” gas network investments. By this she meant to signal the need for investments rendering the network useful beyond 2030. Such investments would permit the transition from natural gas to gases with a smaller carbon footprint. The term of art for this “dual energy system” approach, where natural gas and low-carbon gases hold significant positions alongside electricity from renewable sources, is “sectoral coupling”. Timmermans likewise mentioned this in connect with renewable hydrogen during his own hearing before the European Parliament’s (EP) Environment Committee.

The value of gas as a “bridge” to reach the EU’s clean-energy goals introduces another question into the intra-EU gas debate. Member-states typically disagree over which gas infrastructures Europe really needs. For example, the recent Franco-German compromise on a 2009 gas directive amendment favouring Nord Stream 2 stands in contrast with a European Court of Justice ruling, in a case initiated by Poland and welcomed by Ukraine, which curtailed Gazprom’s access to the onshore German extension of Nord Stream 1.

There is now disagreement over whether Europe needs any further such infrastructure at all. The proposal of the European Investment Bank (EIB) to halt financing of fossil fuel-related projects by late 2020 is here at issue. Two of the EIB’s biggest donors, Germany and Italy, oppose this proposal along with Central European member-states Poland and Latvia. France, along with Sweden and the Netherlands, support it. The EIB’s Board of Directors was therefore unable to take a decision on whether to adopt the proposal at their mid-October meeting; they will reconvene in mid November.

Germany has two reasons to object. First, it aims to diversify its import options in favour of US supplies with the upcoming launch of two LNG projects in its North. Second, after missing its 2020 emission reduction target, it has prepared its 2030 climate plan, which aspires to electrify the transport and heating sectors and to develop a “hydrogen economy”. Natural gas is necessary to both these goals. Simson insisted that the EIB’s lending policy should be aligned with the EU’s climate action, emphasizing renewables and efficiency-promoting projects. At the same time, she said that several gas projects would require co-funding from the EIB.

The Bank’s revised proposal outlines support of gas infrastructure in the EC’s recently adopted Fourth List of Projects of Common Interest (PCIs), and of low-carbon gas projects. This apparently responds to the EC’s carbon-cutting goals, to one of its biggest shareholders climate-gas strategy and to prodding from the European Gas Industry Association (Eurogas), to distinguish between the different fossil fuels.

The revision of the EU’s trans-European energy networks (TEN-E) regulation will also test any European consensus on the future of gas. This regulation defines which infrastructures are eligible to receive grants under the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF). Cross-border infrastructure in the Caspian Sea and in the North Sea have benefited from CEF funding. So have strategic LNG terminals and interconnectors in Southern Europe and the Baltic States.

The TEN-E reform proposal comes in the aftermath of a motion by the EP’s Green group in 2018, demanding that all gas projects be excluded from the Third PCI List. A PCI is a “Project of Common Interest”. Listed PCIs benefit from CEF support. The motion was defeated, but it led the Eurogas head to respond that PCI gas pipelines, as alternatives to existing powerlines carrying electricity generated by coal or lignite power plants, directly contribute to decarbonization and, therefore, complement renewables and energy efficiency investments.

This time around, two factors loom over the discussions. Following the 2019 election, the EP comprises more members from a broader array of political groups, including from the surging Greens; in the less fractured previous Parliament only two groups, the European People’s Party and the Socialists and Democrats, used to prevail. This is also the case regarding the composition of the 96 EP Members (MEPs) from Germany, who strongly influence the balance of power inside the Parliament. Going beyond EP dynamics, there is likely to be a rift between Western Europe (which has good gas interconnections), on the one hand, and, on the other hand, Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans (which do not), over any potential phase-out of EU funding for gas projects. Countries in the latter regions still count on extra gas and LNG infrastructure, particularly since the fate of the post-2019 Russian gas transit across Ukraine remains undecided. Moldova’s push towards the construction of a second pipeline from Romania is an example.

Regardless of predictions about the outcome of the EIB and TEN-E deliberations, Timmermans’s and Simson’s jobs will entail more than just expanding the integration of the gas market in those parts of Europe most vulnerable to monopoly suppliers. They must also manage intra-EU controversies over the need for and types of gas infrastructure, in the context of the new EC’s drive to keep gas at the heart of Europe’s energy transition.

Featured Image: “Major Russian Gas Pipelines to Europe”, via Wikimedia Commons.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.