“It would be the irony of fate if my administration had to deal chiefly with foreign affairs.” These words, uttered by Woodrow Wilson to a friend just days before he became the 28th President of the United States in 1913, would prove more ironic than he could have possibly imagined. Foreign affairs would come to define his presidency, not to mention his name. His eight-year administration (1913-1921) coincided with World War I and the most critical years of its diplomatic aftermath. It was a period that ushered in the greatest sea-change in global affairs since Napoleon. One epoch of world history marked by European colonial empires, great power rivalry, and exclusive economic trade zones, ended with a cataclysmic bang in the trenches of the Western Front; a new era, characterized by the ascendancy of ideals of collective security and free trade, dawned, largely due to Wilson’s soaring public call for a new world order governed by these principles. They did not make their full impact on the world stage until after World War II had convinced the war-weary world that they were wise and necessary. They became incarnate in organizations like the United Nations, NATO, and the World Trade Organization. More importantly, they became part of the zeitgeist of a rules-based international order, a world based on law, not might.

By way of contrast, if there is one word that summarizes the international status this system replaced, it would be “anarchy”. Anarchy in the discourse of international relations does not have the same connotation that it has in the popular imagination – melee chaos. Rather, it signifies a status between states in which power and self-interest are the chief dynamics governing relations between them. For the “realist” school of international relations, anarchy is the natural and immutable way of the world. This concept is easy to understand if smaller social units are understood as microcosms of the world as a whole. For example, relations between individuals within a small town are not typically anarchical, precisely because civil government maintains order. Law, not might, determines the relations between them. Despite their unequal levels of strength or access to resources, individuals in an ordered society receive fair and equal treatment based on the stipulations of the law. However, no higher source of political authority existed above individual states prior to World War I. Thus, the international order functioned like a local town would if it had no constable – there would be anarchy in the sense that access to resources and security could only be found through the use of domineering force against fellows or alliances between individuals against others. Thus, in the anarchic world order that Wilson sought to replace, the most powerful countries of the world dominated the weak, and competed with one another for domination of each other’s resources in an atmosphere of mutual suspicion. Security, if it ever existed, was only tenuously achieved through the building up of national military capacities and by the balance of power existing between rival states. The unsustainability of this system was illustrated by its meltdown in World War I.

Wilson identified the diseased nature of this anarchic global arena with the precision of a pathologist. Secret security arrangements between great powers had created the atmosphere of suspicion and instability that primed the world for conflict in 1914. Wilson’s idea for a League of Nations, an organization in which national grievances could be put on the table and conflicts resolved transparently before a world forum, was integral to diffusing conflicts before they became conflagrations. Moreover, he realized that only free trade and countries’ reliance on comparative advantage would obviate states’ temptations to use military force to dominate resources for economic exploitation.

The tragedy of Wilsonian ideals is that the political classes did not take them seriously enough after World War I. Many European leaders wanted to return to anarchy and secret dealing. Americans chose to isolate themselves. The free trade policies advocated by Wilson ran afoul colonial powers that wished to preserve their exclusive economic zones. When the Great Depression struck in the 1930s, countries retreated behind walls of economic protectionism. This likely made the Depression worse, creating fertile ground for fascism, which in turn led to World War II.

It took this second, tragically avoidable conflict for people to truly understand that anarchy would never make for lasting peace. Wilson, it was realized, had been onto something. The creation of the United Nations as the successor to the League, embodied this collective security arrangement, coupled with the universalization of liberal and democratic values in the form of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This became the moral authority above and beyond the ‘might makes right’ ethos of anarchic international relations realism. Even states that flout the UN’s values feel compelled to acknowledge their legitimacy, even if it is done in a perfunctory spirit. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which became the World Trade Organization, has worked assiduously to lower all trade barriers, excluding onagriculture. Gone were exclusive colonial economic zones. The expansion of free market capitalism has since resulted in the greatest alleviation of poverty in world history.

A century has now passed since World War I ended and Wilson occupied the White House, and there is a strange feeling of déjà vu in the air. Just as Wilson was president at a time of historic change, when the world stood at a fork in the road, the world of today appears to be standing at the edge of another great transition, albeit a transition back to a previous condition. Just as someone who climbs over the crest of a hill begins to descend the opposite slope, back to their original elevation, there are indications that the world is heading back to the pre- rather than the post-World War I order, marked by a resurgence of great power rivalry, a diplomacy of suspicion, and protectionism.

Anarchy, in other words.

The most recent National Security Strategy put forward by the White House makes the indisputable observation that the forces of autocracy are on the rise, especially in Russia and China. Its tone recalls the angst of the Western democracies that feared Germany’s growing power in the lead-up to World War I and then, a generation later, fascism’s gains in Europe. The Trump Administration’s willingness to recognize this threat is commendable. However, in advocating what it euphemistically calls “principled realism,” belittling transnational security arrangements, narrowing its vision of the purpose of the U.S. military to merely being one of defending American national interests, and in advocating economic protectionism, it risks repeating the mistakes made by the Western powers in the preludes to the two World Wars.

The centennial of the 1918 Armistice that ended World War I should give the people of the world, and the people of democratic societies in particular, reason for pause. It should be an occasion for them to ask the question: what kind of a world do we wish to live in? It would be an unmitigated tragedy for the international system, ordered along liberal and democratic principles promoted by Wilson, an order that has resulted in unrivalled economic growth, the expansion of civil liberties, and overall human flourishing, to be supplanted by the archaic system of anarchy it replaced. This should be of particular concern to Canadians. Canada has much to boast about, but it is not a “great power” in the traditional sense of the word. As a country of only 37 million people, with no nuclear weapons, but tantalizing resources, Canada depends on the integrity of the rules-based international order, solidarity with other like-minded democratic states in the NATO alliance, and cooperation with organizations of collective security like the United Nations, for its continued security, independence, and way of life.

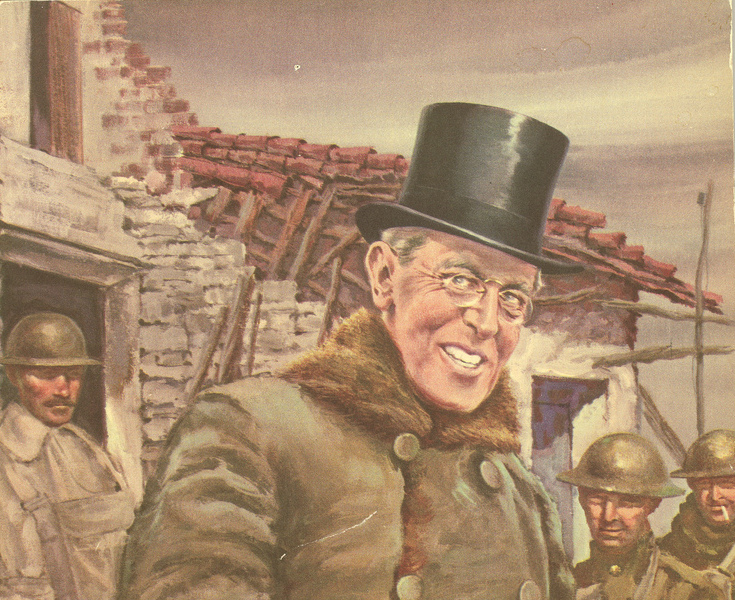

Photo: Portrait of Woodrow Wilson I by Stanley Dersh. From the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library Archives via PICRYL. Public domain.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.