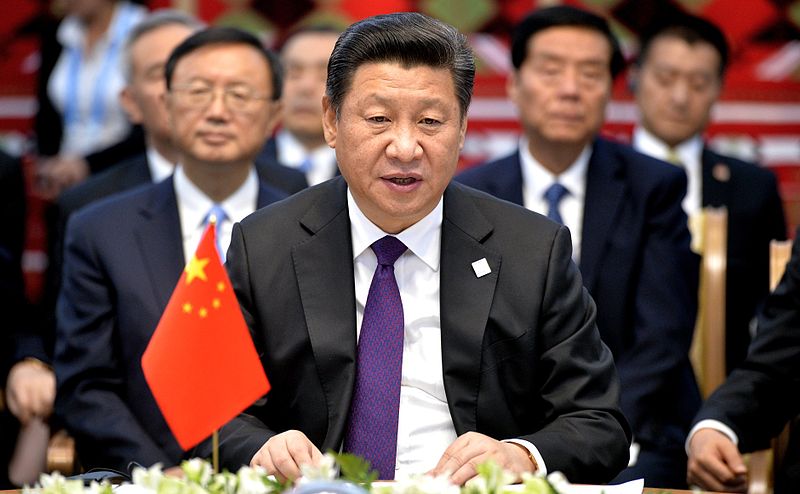

On September 17 2015, China held one of the largest military parades in recent memory, marking the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II and China’s victory over Imperial Japan. The parade featured the latest main battle tanks, attack helicopters and ballistic missiles in the People’s Liberation Army inventory. Much has been written concerning the politics of the parade in Beijing, what the parade revealed however was the power that President Xi Jinping has now accumulated in Beijing, for he was as much at the centre of the parade as China’s victory.

Prior to his ascension to power in November 2012, few would have imagined that Xi Jinping would have been able to achieve such a level of power and influence in so short a period. Little in his background as an unremarkable provincial administrator suggested such a radical streak. His immediate predecessor Hu Jintao was widely viewed as weak, lacking full control of the state apparatus and military due to the placement in key sectors of China’s economic and security architecture of individuals loyal to Jiang Zemin. Such was his influence that Jiang only formally relinquished his role of head of the Central Military Commission in 2005, over a year into Hu’s presidency. Xi Jinping, who served as vice president under Hu Jintao, however has sought to roll this back, undoing the networks of patronage and nepotism. Xi now stands unopposed in an attempt to create a cult of personality surrounding his premiership. This vision of one-man rule in China has not been seen since the days of Deng Xiaoping, the core of China’s post-Mao leadership.

The core leadership

As the head of the military, the party, and the state, Xi Jinping is afforded multiple titles. In the Western press he is referred to simply as China’s president, but Xi also serves as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China and Chairman of the Central Military Commission. Within the Chinese government, Xi is already known to directly chair multiple policy planning committees on foreign policy, Taiwan, and the South and East China seas. Whilst always having the final say on foreign policy, President Xi’s decision to directly chair these committees represents an expansion of the role of the president, well beyond that undertaken by his immediate predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin.

Indeed this consolidation of government policy around Xi Jinping has continued amid recent turmoil within China’s economy. Following the August 2015 upheavals in China’s primary stock exchange, Xi reduced Premier Li Keqiang’s overall control of economic policy after his perceived mishandling of the Shanghai Index crisis, which saw almost $1.5 trillion USD wiped out amid a speculative bubble and 2% devaluation of the Yuan. Indeed by further expanding his role in the economic sphere, it has been argued that Xi Jinping seeks to remove Li Keqiang outright, in favour of loyalist Wang Qishan. The factional equilibrium within the Chinese Communist Party is such that Li, who remains close to former president Hu Jintao, cannot be removed without significant upheaval. However Xi Jinping was able to sideline him from policy making in favour of Liu He, the president’s chief economic adviser.

As recently as April this year, Xi awarded himself yet another title, assuming the mantle of Commander in Chief of the Joint Operations Command Centre in Beijing. The new command and control facility, established in 2014, coordinates all three branches of the People’s Liberation Army. Through this latest consolidation of power, Xi has direct military control of the PLA in addition to the political control afforded to him already as Chairman of the Central Military Commission. With deferential coverage on state-run media, Xi visited the underground facility in a PLA camouflage uniform with two vice-chairmen of the Central Military Commission, Fan Changlong and Xu Qiliang. Though this move is not without precedent, it is nonetheless unusual for a Chinese leader post-Mao to dress in military fatigues. As with the Victory Day parade in Beijing, it was an overt display of direct presidential control over the People’s Liberation Army.

In December 2015, Xi took on the additional title of ‘Core of the Leadership’. In contrast to the other titles, this is largely a symbolic one internal to the Communist Party. However its importance lies in the fact that it has only ever been afforded to one other leader in the post-Mao era, Deng Xiaoping, who applied it to himself after his 1979 reform of the CCP leadership into a consensual, collective governance structure.

Since then, General Secretaries of the Communist Party such as Hu Yaobang, Zhao Ziyang, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao have not been afforded the title, because no leader since Deng has been able to consolidate enough political power amongst the various party factions to legitimise his use of the title. Jiang Zemin came closest to achieving such power (via cronyism and corruption) by effectively creating a state within a state, layering the Communist party and military with tribunes loyal solely to him. In the last three years, XI has dismantled this system, isolating Jiang, as key lieutenants such as former security chief Zhou Yongkang and Vice-Chairman of the Central Military Commission Xu Caihou have been arrested and their assets seized, leaving Xi Jinping the most powerful figure within the Communist Party.

A growing cult of personality

What is apparent is that Xi Jinping is securing a power base not only within government but also among the wider Chinese public. Xi’s consolidation of power in Beijing is increasingly being matched by what many observers have termed a nascent cult of personality. Since assuming power, the Xi administration has demonstrated increasingly authoritarian, even Maoist, tendencies, launching diatribes against the cultural and political influence by foreigners, while at the same time state outlets such as Xinhua, the People’s Daily, and the international broadcaster CCTV have presented fawning coverage of Xi.

This rise of personality cult comes at an incredibly sensitive time for China. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution, launched by Mao Zedong to reclaim control over the CCP through purges that saw over 2 million people killed by Mao’s Red Guards and much of China’s cultural heritage destroyed. The party has shown incredible reluctance to even acknowledge the anniversary, let alone allow comparisons between Mao Zedong and Xi Jinping. Editions of Time Magazine and The Economist that have done so have been banned in China. A recent controversy in China regarding depictions of the Cultural Revolution has revealed a potential power struggle against the increasing centralisation of personal and political power by Xi Jinping.

In early May, a Maoist themed Cultural Revolution concert that included Red Guard songs from the era calling for “people of the world unite to defeat American invaders” was held in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. At repeated intervals, images of Xi Jinping appeared alongside Chairman Mao as the 56 Flowers choir extolled the virtues of the ‘Great Helmsman’ and the Cultural Revolution, inferring Xi was comparable to Mao Zedong.

Such a comparison is politically poisonous in China, as the post-Deng Xiaoping decentralised structure of the CCP is intended to never again allow one-man rule and the cult of personality in China. In 2012, Bo Xilai the Communist Party Secretary of Chongqing was arrested for attempting to revive such a Maoist personality cult at the regional level. It has been suggested that forces within the CCP close to Jiang Zemin deliberately arranged for the concert to take place in order to portray President Xi’s leadership as a Mao-style personality cult.

Tellingly two days after the Maoist concert, Xi gave a speech warning ‘cliques and conspirators’ were active within the Communist Party seeking to undermine his government. The question now is, just how secure is Xi Jinping’s position? On the face of it, his control of the party, government and military seems absolute, but Chinese history is replete with emperors whose control was unquestionable right up until the moment it wasn’t. The system designed to avoid one-man rule in China is beginning to strain. For now Xi Jinping is China’s most powerful leader since Deng Xiaoping, but for how long?

Photo: “Xi Jinping, BRICS summit 2015” (2015), by Пресс-служба Президента России via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.