The withering democracy in South Korea today largely reflects the problem within its foundation. The legacy of war made it difficult to reconstruct South Korea into a society respecting the rule of law, fairness, and equity as the ex-collaborators were pardoned and became patriots. The ruling elites and the chaebol, the wealthy families that would later become multinational conglomerates, felt these crucial elements of a just society were unimportant. As a result, corruption, opportunism, and injustice is rampant in South Korea today.

Like South Korea, the winners had already been chosen from the beginning in the independent Ukraine. The problems deriving from its foundation cannot be improved overnight. But in contrast to South Korea, the memories of the triumph over Yanukovych are still fresh among Ukrainians. The societal change, no matter how slow it might seem, is in progress. Despite Ukraine’s being in the midst of a war and that the economic collapse may be imminent, Ukrainians continue to show an incredible level of resilience. They have shown that they are capable of taking a step further towards a bright future.

A society without rules

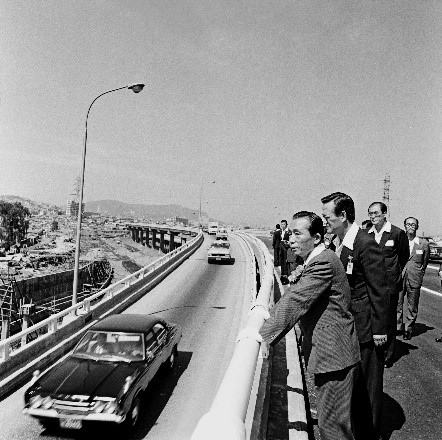

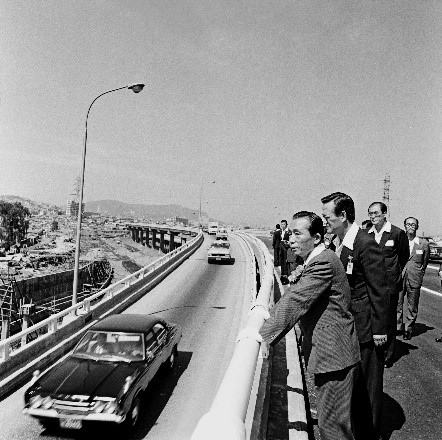

In South Korea, the winner had already been chosen from the beginning. In the 1960s, the policymakers concluded that it was best to grow large firms that would produce manufactured goods for export. The Chaebols, who owned these firms, could easily grow their wealth and power as they had received assistances including the low-interest loans and trade protection. The chaebols sought to create more opportunity for themselves by paying bribes. Meanwhile, the emphasis on the rule of law, fairness, and equity was largely overshadowed by Park Jung-hee’s strong desire to turn South Korea into an export powerhouse at all costs.

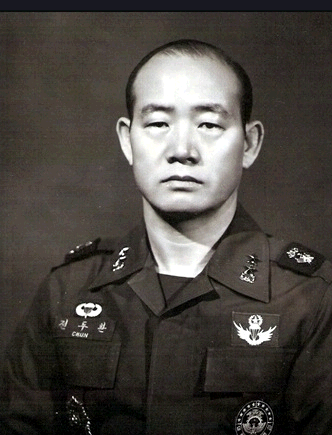

The collusion between the business and the ruling elites could not simply be broken by the change in leadership and policy. Chun Doo-hwan, a member of a junta which launched a coup shortly after Park’s assassination in 1979, introduced stabilization measures to control inflation. Although the policy reduced the public’s anger towards his regime, Chun refused to tolerate labor and democratization movement. Under Chun, the laborers and students demanding recognition of their rights had to endure torture and death. The corruption in society remained intact. Chun and his family became chaebol themselves by using their power to collect bribes from the chaebols.

The collusion between the business and the ruling elites could not simply be broken by the change in leadership and policy. Chun Doo-hwan, a member of a junta which launched a coup shortly after Park’s assassination in 1979, introduced stabilization measures to control inflation. Although the policy reduced the public’s anger towards his regime, Chun refused to tolerate labor and democratization movement. Under Chun, the laborers and students demanding recognition of their rights had to endure torture and death. The corruption in society remained intact. Chun and his family became chaebol themselves by using their power to collect bribes from the chaebols.

The economic development which began with benefiting the few and neglecting the essentials for a healthy society created a widespread belief among the ruling elites and the chaebols that they could avoid punishment for their crimes. Even Chun, the mastermind of the massacre in 1980 who was a ruthless dictator for seven years, was pardoned in 1997. The court ruled that Chun could not be punished for his “successful” coup. Although the court ordered him to return his slush funds to the state, he brazenly claimed in 2003 that he could not pay the full sum because he only had 290,000 won ($300 USD).

Imbued with greed, the government’s obsession with economic growth eroded the respect for rule of law, fairness and equity in South Korea. It also led to a situation where wealth and power can be a guarantee of immunity for crimes. Since the memories of people working together for a just society are fading, it is uncertain whether South Korea can improve its quality of democracy soon.

A lingering hope for Ukraine

Like South Korea, the independent Ukraine had chosen a wrong economic policy. The hasty liquidation of the Soviet-era state industries allowed a small group of people to possess an enormous wealth and prestige. The efforts to address foundational problems after the Orange Revolution were unsuccessful as the leaders destroyed the synergy for change by engaging in endless political feuds. As a result, many oligarchs continued to use illegal means to achieve their ends and the corruption became uncontrollable during Yanukovych’s presidency.

Even after the Euromaidan, some oligarchs have acted as if the unlawful means could still achieve their end. Andrew Wilson claims some oligarchs, who had ties with Russia, purposefully supported the separatists in the beginning. Such treacherous acts were committed with a false hope that the crisis in the east would give them more bargaining power in Kyiv. The danger of Ukraine’s returning to its dark past remains alive as the lustration reforms have been progressing slowly.

Nevertheless, the Euromaidan did set a precedent that the people would not stand idly under the corrupt regime. Thankfully, change is taking place in Ukraine. Politicians now hesitate to ask for a bribe, and bureaucrats can no longer cover up corruption as brazenly as they did before the Euromaidan. It is praiseworthy that Ukraine continues to march on the road to normalcy—even in the darkest times.