Since 9/11, the battle over women’s rights has taken centre stage in Afghanistan, both during wartime, and now as troops have begun to withdraw from the country. In the name of “neutrality and impartiality”, peace building has been entangled in Afghanistan with security and counter-terrorism efforts. As part of its defense strategies, the West has waged multi-faceted campaigns targeted to “de-legitimize” the reigning ideologies, which empower the Taliban to maintain its control over key Afghan regions. One of the main focuses of this war has been the rights of Afghan women, whose lifestyle choices and freedoms have come to symbolize the “success” of each side.

Peace talks addressing Afghanistan’s post-war transition have ensued, but the voices and opinions of Afghan women on the ground are largely excluded from peace and security agreements.

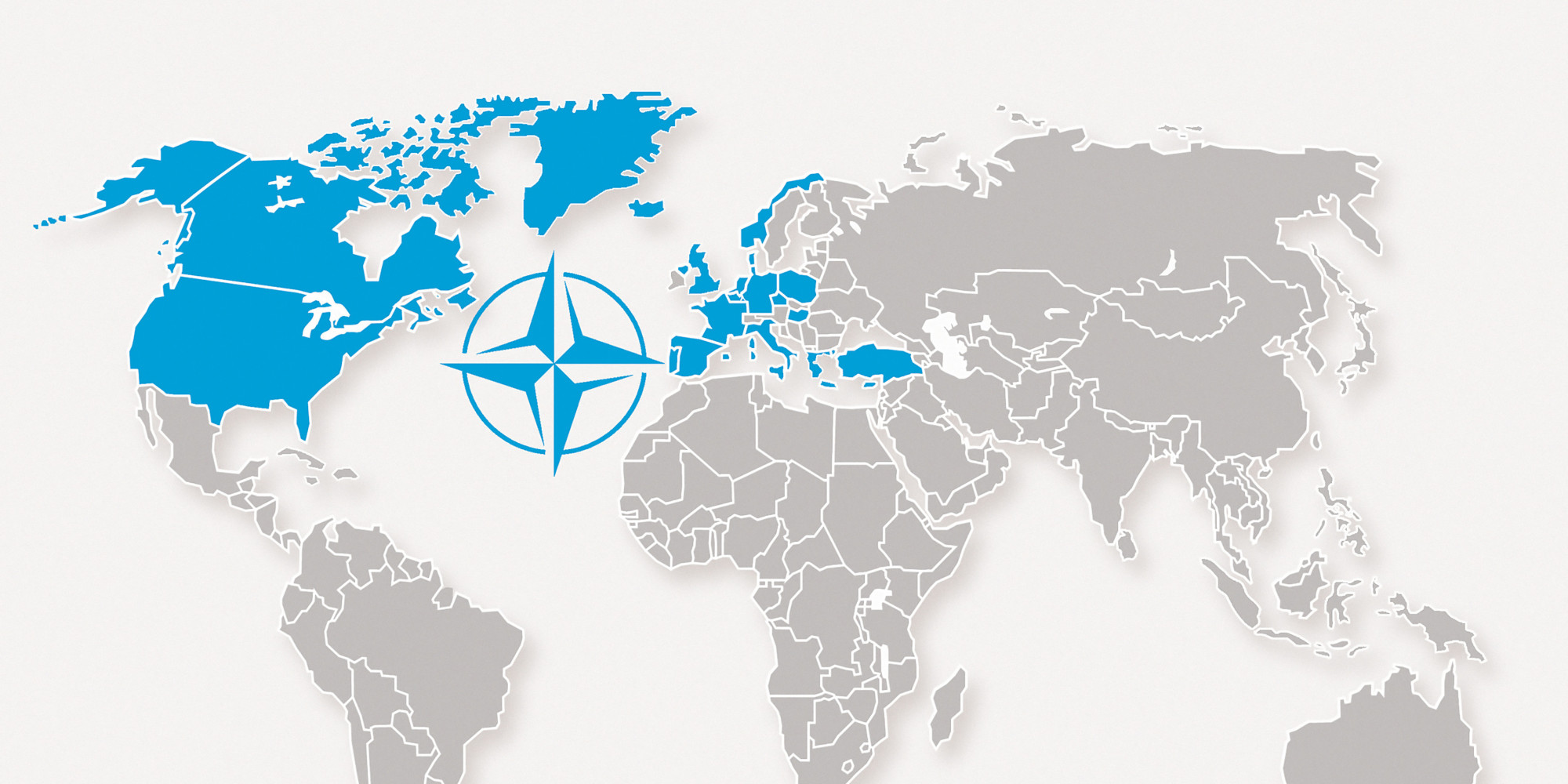

The “liberation” of these women from oppression has increasingly come to be reduced to single issues related to religion, such as “freedom from the burqa [veil],” while women’s basic needs, such as easy access to water or sanitation have sometimes fallen by the wayside. As a result, the US and NATO allies’ counter-terrorist strategies, including coverage of “events on the ground” by Western media, have prioritized what women’s rights “represent” over what rights and opportunities Afghan women on the ground really need.

On the other hand, for the Taliban, the battle over “women’s rights” in Afghanistan has resulted in the restriction of women to the home, and has manifested in the strict enforcement of the burqa as a symbol of obedience. For these extremists women’s empowerment has unfortunately become synonymous with unwanted Western domination.

Throughout this ongoing battle over women’s rights a troubling condition persists: peace talks addressing Afghanistan’s post-war transition have ensued, but the voices and opinions of Afghan women on the ground are largely excluded from peace and security agreements.. In fact, the inclusion of women as signatories in Afghanistan’s peace processes from 1992 to 2011 has maintained an alarmingly low rate of 9%, while no groups serving Afghan women’s interests have been invited to the peace processes between Western powers and Afghan representatives.

Most critically, there is a lack of engagement and dialogue with the local women and even less inclusion of these women’s narratives, priorities, and needs into the structural and institutional changes that support peace and security for the region.

Canada and fellow NATO member nations have an obligation to ensure that peace and security be achieved, by continuing to employ counter-terror strategies. However, the entangled web of women and security should not, in the name of heralding women’s rights, silence the voices of the very women we seek to help.

If the aim of Canada and its NATO allies is to truly assist these women to obtain their rights to autonomy and desired equality, it would be to our interests to familiarize ourselves with these new facets of war and security inherent in the war of ideologies, and to alter our current security and development approaches by engaging in inclusive and collaborative dialogue with the Afghan women whose rights have such importance for post-war peace.