August was a grim month for the European Union; a variety of economic indicators suggest that the region is on its way to a third recession in six years. GDP declined by 0.2% last quarter in Germany and Italy, while France’s economy remained stagnant. Collectively, these three countries make up two-thirds of the EU economy, so higher growth in smaller nations like Spain and the Netherlands cannot make up for the contraction. Manufacturing and business growth were the slowest in over a year, and the threat of deflation looms as the inflation rate fell to 0.4%, well below the ECB’s target of 2%. Adding to the issue are the latest sanctions put in place by Russia, impacting agricultural exports in every EU nation. A prolonged downtown in Europe could have ripples on the world economy, limiting consumer markets for U.S. and Canadian products.

August was a grim month for the European Union; a variety of economic indicators suggest that the region is on its way to a third recession in six years. GDP declined by 0.2% last quarter in Germany and Italy, while France’s economy remained stagnant. Collectively, these three countries make up two-thirds of the EU economy, so higher growth in smaller nations like Spain and the Netherlands cannot make up for the contraction. Manufacturing and business growth were the slowest in over a year, and the threat of deflation looms as the inflation rate fell to 0.4%, well below the ECB’s target of 2%. Adding to the issue are the latest sanctions put in place by Russia, impacting agricultural exports in every EU nation. A prolonged downtown in Europe could have ripples on the world economy, limiting consumer markets for U.S. and Canadian products.

In a speech in late August, the president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, suggested the need for a change in many EU nations’ fiscal policy and economic structure. The ECB decides the region’s monetary policy by manipulating interest rates and the money supply. However, nations within the union have the ability to control fiscal policy (taxes and spending) and the structure of their economy, leading to very different economic outcomes across nations. Some of the region’s leaders denounced Mr. Draghi and perceive his comments as overstepping his authority, while others simply disagree with his ideas.

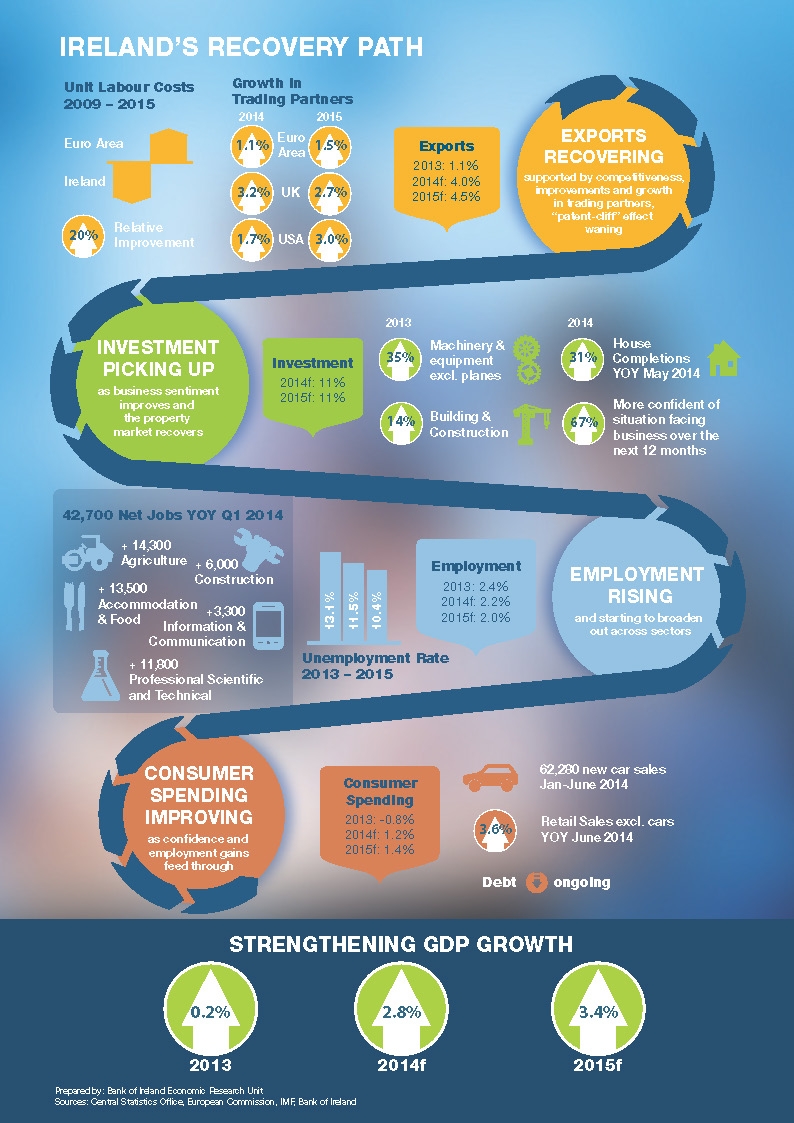

Ireland, a country whose economy was in such danger it needed a bailout several years ago, can be used as examples of how a combination of fiscal policy and structural reforms can save an economy. In 2014 GDP growth in Ireland will reach 5%, its highest rate in 6 years. Confidence in the economy has risen, creating a domino effect of more investment, higher employment and more consumer spending. Politicians often blame the policies of the ECB for their sluggish economies and not their own rigid economic structure, but the case of Ireland offers evidence that sometimes, a radical change can foster growth in unexpected ways.

Following the ECB and IMF bailout of $85 billion in 2010, Ireland went through a series of reforms outlined in its 2011 National Recovery Plan. One of its major goals included “dispelling uncertainty and reinforcing the confidence of consumers, businesses and of the international community”. The government acknowledged the challenges and the necessity of tightening the national budget: “the tax and expenditure measures contained in this Plan will negatively affect the living standards of citizens in the short-term. But postponing these measures will lead to greater burdens in the future.”

Some of the measures put in place addressed structural issues; for example, businesses were granted more control over wages, antitrust laws were strengthened and the age of retirement raised. The public sector underwent significant reform; government staff was cut and public institutions were split into fewer, smaller departments. Export growth and increased competitiveness were stimulated through funding for innovation, R&D and global marketing. Labour market mobility was also stimulated through increased skill training programs, internships and more targeted education. Welfare reform stimulated and helped the unemployed to find work. Employment rates rose by 3% since 2011 and are on target to continue to rise in 2015.

In terms of fiscal changes, the Irish government decreased its annual spending gap (debt accumulation) from 20% of GDP in 2010 to 3% in 2013. Over the last 3 years they saved €15 billion from the budget by reducing spending by €10 billion and raising €5 billion in tax revenue. Several new taxes were introduced, including a carbon tax, pension tax, and a 1% increase in the value added tax. All of these measures brought the national debt down to a more stable level, increasing the confidence of investors in the strength and stability of the economy.

Economic models project Ireland’s growth to continue for the next two years, an amazing feat for an economy that collapsed only 4 years ago. The right mixture of fiscal and structural policies are sought after by governments worldwide, but Ireland seems to have hit the right note. Its bold but effective reforms have been the catalyst for a chain reaction that has led the economy to stimulate itself into a cycle of growth.

hana maqsood