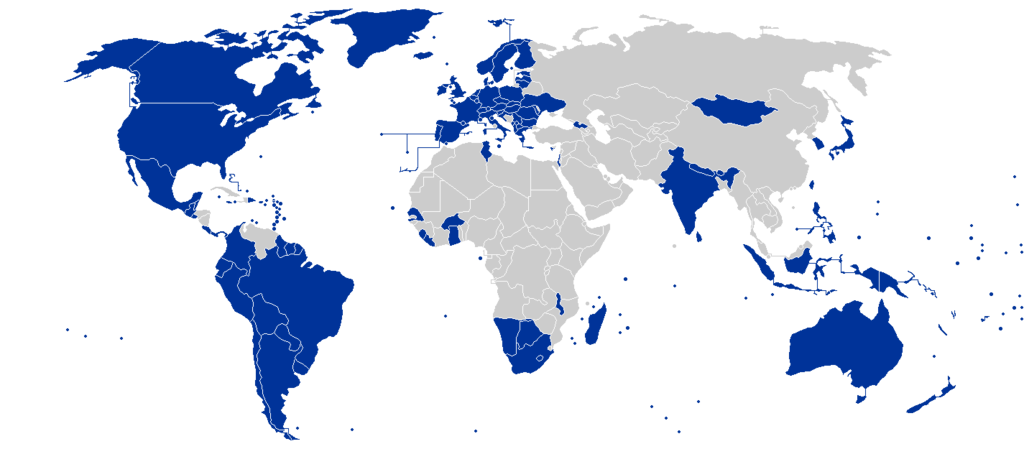

In the 1990s, the idea of ‘democracy aid’ was introduced to guide developing countries towards democracy. The introduction of democracy aid initially sparked great optimism, gaining the support of multiple Western democracies. In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, many believed that democracy would spread worldwide, that Western liberal democracy would have no competitors, and that the influence of Western democracies would continue to increase. Despite the high levels of optimism and high levels of Western participation, continuous negative developments have since toppled the optimism once felt in the 1990s. Today, more than $10 billion is spent on democracy aid annually, but why does democracy aid continue to produce lacklustre outcomes and what may we see in the coming decades?

Democracy aid is built upon three fundamental features: the development of key democratic institutions/processes required for party competition; the establishment of institutions and checks on power; and the development of support for civil society (labour unions, education, etc.). After 30 years, these core fundamentals continue to play a central role within the program. The program continues to develop new strategies over time and continues to learn from past mistakes. For example, democracy aid no longer uses a single strategy but has transitioned to using country-specific approaches. As a result, a standard menu has developed, outlining techniques that may be used in certain scenarios. This program is flawed, however, as the strategies may not apply in all scenarios. For this reason, the program continues to develop and learn from past experiences.

Although beneficial, the standard menu’s cons may outweigh the pros. Small organizations designed for democracy aid think strategically and go beyond the standard menu. However, larger institutions, in which democracy aid is a small part of their business, continue to rely on the standard menu and operate on strategic autopilot. These groups put little thought into their strategies, failing to pinpoint key problems in transitions and undercut the efforts of smaller strategic companies. Autopilot strategies fail to pinpoint key issues and often result in a failure to transition.

Aside from the technical issue, another factor leading to the continuous decline in democratic momentum is the rise of anti-democratic powers. Developing and transitioning countries tend to imitate powerful states, attempting to replicate their success. Therefore, the rise of anti-democratic powers, such as China and Russia, instigates a debate over which governmental system one should adopt. Alternative rising powers also hinder democracy aid as they use their influence to challenge the program.

The power of oil creates continuous barriers for democracy aid. Over the past decade, the United States continues to demonstrate a weakened commitment to challenging oil-rich countries. Democracies must continue to maintain strong relationships with oil-rich countries due to the reliance on fossil fuels. Oil continues to play a crucial role in preventing the penetration of democracy aid in parts of the Middle East.

A Look into the Future

The reduction in the growth of democracy worldwide is at least partly due to complications from oil-based countries. Most countries are now democracies; 123 out of 193 countries globally, and a majority of the non-democratic regimes rely on oil as a major national industry. In the Arabian Peninsula, oil is power. When a country has oil, democracies cannot spread their influence. Oil money is used to ensure there is political stability through subsidization and increasing citizen benefits.

Although democracies such as Canada and the United States also rely on the production of oil, these democracies tend to consume much of the oil rather than export. The United States produces the largest portion of the world’s oil at 14% of global production with Canada ranking fourth place with 5%. However, when looking at oil exports, America does not even rank within the top five countries and Canada ranks fourth with 7% of global exports. Saudi Arabia, Iran and Iraq all rank within the top five oil-exporting countries with 16%, 8% and 5% of global exports. Heavy reliance on oil exports helps mitigate the necessity of higher taxes.

The world is entering a phase where countries are now looking to reduce their dependence on fossil fuels. The climate crisis will lead to the development of alternative energies, reducing the power of autocratic regimes that rely on oil revenue. Although the weakening of oil regimes may lead to an increase in democratic influence, one must be wary of the rise of authoritarian powers, i.e. China. The oil-rich regimes of today may look towards replicating the success of authoritarian powers, creating a further barrier to democratic influence. However, replication of such regimes may prove to be more difficult, for reasons tied to the political economy of these states.

The monetary benefits of oil allow oil-rich regimes to continue to successfully maintain their authority because they do not need to tax their citizens due to the large revenue generated through oil industries. When these regimes sense public unease, they use oil money to increase citizen benefits to prevent civil unrest. If such countries aim to replicate the success of China, they will face civil unrest due to the system’s design. Civil suppression will lead to increased protests, and without the continuous inflow of oil money, the system will not be able to sustain itself. There will most likely be a transition towards a more democratic position as continuous citizen support is essential in these regimes.

The past of democracy aid should not be used to analyze the future trajectory of the program. We will likely see a change in natural resource dependence play a major role within the impact of democracy aid in the Middle East. Although China does pose a threat, the toll of implementing their system may be too high as oil-rich regimes tend to rely on being able to purchase political stability through benefits distributed as a result of oil revenues. Overall, one may be hopeful for the future of democracy aid, however, it is too early to tell. One must consider the possibility of rival powers spreading their influence as the United States continues to show a lack of commitment to maintaining democratic values abroad.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.

Photo: an image of electoral democracies around the world by Joowwww (2008) via Wikimedia Commons