Introduction

April 7, 2014 marked the twentieth anniversary of the start of the Rwandan genocide. Over the course of three months, the ruling Hutu majority conducted a systematic campaign of violence against the minority Tutsis, killing roughly 800,000 people. Though the massacre still casts a long shadow over the small Central African state, the past two decades have seen Rwanda undergo a significant transformation, becoming a rare success story in the conflict-ridden Great Lakes Region. Rwanda may be a more prosperous and stable state now, but the road to recovery has been long and reconciliation with the events of the past is still ongoing.

While the genocide was a domestic conflict, perpetrated within Rwanda by Rwandan citizens, the number of casualties might have been lower if the international community had made more efforts to halt the violence. With few countries having any sort of strategic interest in Rwanda, the international community turned its back and allowed the violence to perpetuate with almost no resistance. The realization of the magnitude of the bloodshed following the conflict led to scathing condemnation of the United Nations for its failure to intervene. Even today, the UN remains haunted by its decision to stay on the sidelines, with Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon referring to the UN’s inaction as shameful at a ceremony in Kigali in April marking the anniversary of the genocide.

In the wake of the genocide, the international community realized the necessity of an expanded mandate on the use of force for humanitarian interventions, and in 2005, the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine was adopted as a means of ensuring atrocities like the Rwandan genocide would never occur again. As such, the crisis profoundly changed the way states respond to and address mass acts of violence perpetrated inside the borders of another sovereign state. This two-part series will examine the origins and events of the Rwandan genocide, and will discuss the reaction to the crisis and its future implications.

Rooted in History

The 1994 crisis has its roots implanted in Rwanda’s colonial past. Germany was the first European power to colonize Rwanda in 1899, but after its defeat in the First World War, Rwanda became a mandate of the League of Nations and was administered by Belgium starting in 1919. In Rwanda, two prominent ethnic groups exist: Hutus, who have historically represented a significant majority of the population, and Tutsis. Though characterized as two very distinct ethnic groups, with Tutsis stereotypically described as being taller, thinner, and lighter-skinned than Hutus, anthropologists assert that Hutus and Tutsis are practically indistinguishable racially. Nonetheless, it is believed that the Tutsis of Rwanda migrated there from Ethiopia some 400 years ago and integrated with the Hutus who were already present in Rwanda at that time, adopting the same language and practices as the Hutus. However, the two groups diverged along class lines, as the Tutsis, who were cattle-herders, occupied a more profitable occupation than the Hutus, who were agriculturalists.

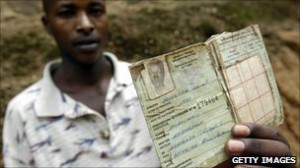

As the wealthier group, Tutsis began to occupy elite administrative positions in pre-colonial Rwanda, although Hutus were still able to climb the social ladder and become successful. The innate inequality between the Hutus and Tutsis in Rwanda created only minor tensions between the two groups, but they were exacerbated by the arrival of the Belgians who heavily favoured the Tutsis. Hutus no longer had the social mobility they enjoyed in the past as only Tutsis were given access to Western-style education, and the Belgians backed the Tutsi monarchy and gave high-level governing positions exclusively to Tutsis. The Belgians further cemented ethnic division by issuing identification cards that distinguished Rwandan Hutus and Tutsis from each other.

Independence and Ethnic Conflict

During the late 1950s and continuing into the early 1960s, the Hutus rebelled against the Tutsi rulers propped up by the Belgians. As the Hutus began to organize their own political groups and demand greater representation, hundreds of thousands of Tutsis fled Rwanda as fighting broke out between the two ethnic groups. Rwanda independence in 1962, with Hutu Gregoire Kayibanda becoming president, and throughout the 1960s and 1970s Hutu extremists massacred scores of Tutsis and forced many more into exile. In 1973, a military coup toppled the Kayibanda government and General Juvénal Habyarimana seized power, drafted a new constitution, and subsequently won the presidential election of 1978. Habyarimana, also a Hutu, established policies that heavily favoured Hutu Rwandans at the expense of the Tutsis, giving Hutus preference in public service and military jobs.

While the repression of Tutsis in Rwanda continued into the 1980s, across the border in Uganda Tutsi refugees began to organize themselves into an efficient and effective military force. In 1988, a rebel military group called the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) was founded and in 1990, the RPF launched a successful cross-border offensive from Uganda. With the RPF’s advances putting pressure on the Habyarimana regime, the Hutu establishment intensified its anti-Tutsi propaganda campaign, portraying all Tutsis, and even moderate Hutus, as traitors in the likes of the RPF. Despite a peace agreement being reached in August, 1993, between the RPF and the Rwandan government and the peacekeeping operation of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) beginning two months later, Tutsis and Hutus still harboured intense disdain for one another. The peace process only created an illusion of security in Rwanda, and in reality the state remained a powder keg, ready to be set off by the slightest spark.