India’s submarine force has the misfortune of being infrequently mentioned unless there is a report on its diminishing size or an accident. As previously argued, Indian naval doctrine is centred on sea control through aircraft carriers and surface warships. Even so, India has made substantial investment in its submarine fleet in past decades. The government of Narendra Modi appears to be willing to commit India to substantial investment in the navy’s undersea arm in order to make up for a lost decade of procurement, to provide escorts for India’s aircraft carriers and to provide a sea-based nuclear deterrent. Meanwhile, despite the government’s making substantial commitments, the navy’s submarine force faces a number of serious challenges that cannot be resolved any time soon.

Although its force structure is primarily oriented towards sea control, the Indian Navy has a standing requirement for a twenty-four-strong fleet of submarines. This ambition has yet to be realized. Since the fatal fire that sank Sindhurakshak pier-side in 2013, India only has a fleet of fourteen submarines. This fleet is composed of a single leased Russian Bars-class nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN), four German-designed Type 209/Shishumar-class diesel-electric submarines and nine Soviet/Russian-built Kilo/Sindhughosh-class diesel-electric submarines. This fourteen-strong inventory of submarines is reduced once vessels laid up for refit are taken into account, including the Sindhukirti, a Kilo-class submarine that has been stuck at a dock since 2006 as a result of a botched attempt at a refit. Worse still, the average age of the thirteen diesel-electric submarines is a remarkable twenty five and a half years, with the youngest submarine at a mid-life age of 15 years.

In order to meet the requirement for a twenty-four-strong fleet of submarines and to modernize its ageing fleet, New Delhi signed a contract in 2005 for six French-designed Scorpene/Kalvari-class diesel-electric submarines. The contract required the production of the six by an Indian shipyard. As a result of delays at that shipyard, the vessels, originally intended to be commissioned between 2012 and 2017, are now expected to enter service between 2016 and 2021. By the time the last Scorpene is expected to enter service in 2021, the submarine it will be replacing will be, at best, thirty-two years old. Although the Scorpenes’ introduction is eagerly anticipated, the six submarines will not solve India’s submarine woes. As a result, an additional six submarines of a yet to be determined type are being procured under the long-delayed Project-75 India (P-75I). The aim of the new project is to find a suitable replacement for India’s remaining old diesel-electric submarines. Because New Delhi has decided to produce these yet to be selected submarines at Indian shipyards, the first submarine is unlikely to be introduced until the mid-2020s and the last by around 2030. By then, the youngest of India’s existing diesel-electric submarines will be a worrying thirty-six years old.

India will be procuring only twelve diesel-electric submarines to replace a fleet of fourteen submarines, if one includes the submarine lost to fire. Not only does this mean that India’s submarine force will shrink, it will fall far short of the target of twenty-four submarines. New Delhi seeks to meet its target by leveraging India’s current development of a nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN, these are separate from the requirement for 24 attack submarines) to build at least six nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSN). The purpose of the SSBNs is to carry nuclear-warheads mounted on ballistic missiles. SSNs, on the other hand, are attack submarines similar in function to India’s existing diesel-electric submarines. Moreover, the high sustained speeds of SSNs and their theoretically unlimited range make them ideally suited to escorting India’s aircraft carriers. It is unknown when the first SSN will enter service but given the size of the order and India’s simultaneous construction of SSBNs, New Delhi is extremely unlikely to commission them before the early 2020s.

Yet even after the 12 new diesel-electric submarines and the six SSNs are taken into account, India will, at best, only have 18 submarines by the mid- to late-2020s. Building submarines takes a long time, particularly for new designs such as the Scorpene, and P75I. This leaves India six ships short of its target. Other than reducing its target, New Delhi can order submarines produced by foreign shipyards or undertake a massive but risky and rather implausible effort to dramatically increase its submarine building capability, something it already has to do to build the six SSNs and six P-75Is. Even though the building of six SSNs would noticeably improve India’s naval capabilities, it does so at a great opportunity cost. Nuclear powered submarines cost around twice as much as diesel-electric submarines.

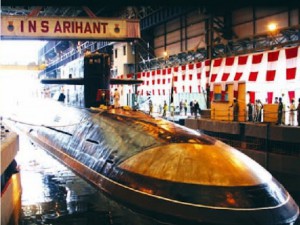

In 2009, India took the notable step of launching from a dock the Arihant, the first of possibly four or five Arihant-class (SSBN). The purpose of these SSBNs is to carry nuclear-armed ballistic missiles at sea, so as to provide India with a survivable second-strike nuclear retaliatory capability. The Arihant, India’s first indigenously constructed nuclear-powered vessel had its reactor turned on in 2013, which was an important step towards its formal commission anticipated for 2015. Though more submarines of the class are understood to be under construction and on order, it is unclear when India will undertake its first submarine-based nuclear deterrence patrol.

The Indian Navy, like all navies, was initially hesitant about acquiring SSBNs, fearing that the multi-billion dollar vessels would hurt its shipbuilding budget to the detriment of the modernization of its surface combatants, aircraft and other submarines. It is unclear yet whether such fears have become reality. India’s economy has much potential and the future for the navy’s shipbuilding budget may be promising but, at present, it appears that the SSBN project may have proved costly to India’s submarine modernization, notwithstanding its provisioning India with the capabilities required to build SSNs.

India’s submarine force has a long way to go to complete its modernization by replacing its existing vessels, let alone meeting its stated goal of having a fleet of 24 submarines. Despite a series of delays in construction and decision-making, India has made a number of important decisions about the future of its submarine fleet that should allow New Delhi to remain the primary naval power in the Indian Ocean.