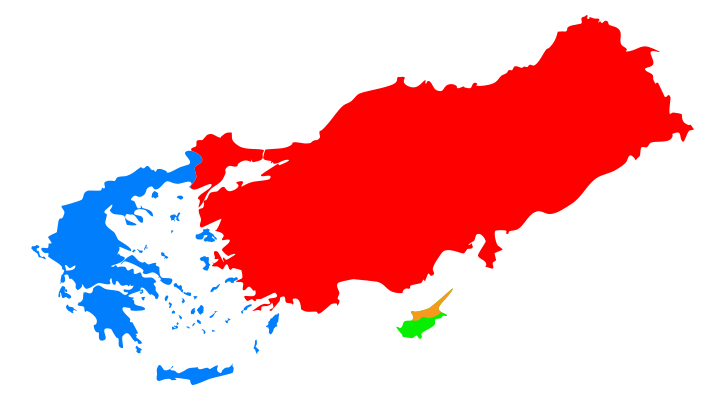

Along with the Covid-19 Pandemic and the US Presidential election, the news cycle has been dominated by the resurgence of conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, a Caucasus region contested by both Armenia and Azerbaijan. Armenian and Azerbaijan are locked in what is known as a frozen conflict, where active conflict has ended but no formal peace treaty exists to formally reconcile the issue. Yet while one frozen conflict on the edge of Europe (geographic Europe ends a few hundred kilometers away from Nagorno-Karabakh in northern Georgia) dominates headlines, there have been other recent developments that pertain to a frozen conflict within Europe itself, though it has received far less attention. Northern Cyprus, a de facto state-recognized solely by Turkey, announced plans to reopen parts of Varosha, a ghost town closed since the 1974 Turkish Invasion of Cyprus, an EU member state in the eastern Mediterranean. Since the invasion, the island has remained divided with an internationally recognized Greek-Cypriot state in the southern portion of the island while a Turkish-Cypriot State controls the northern third. That the reopening of Varosha is a barrier to a permanent peace agreement represents the complexity of Cyprus’ geopolitical situation. This article will contextualize this recent development while elaborating on how energy can serve as an avenue for lasting peace on the island.

Of Cyprus’ 1.1 million inhabitants, 78 percent are Greek Cypriots while 18 percent are Turkish Cypriots. The island was formerly occupied by the Ottoman Empire and more recently by the British as a formal colony. Ethnic tensions grew, the question over the state of a decolonized Cyprus increased in complexity. Some Greek-Cypriots sought for a union with Greece, while some Turkish Cypriots sought union with Turkey. Others wanted an official partition of the island between both Greece and Turkey. Rather than these options, a unified, independent Cyprus was created in 1960, with a Greek Cypriot President, a Turkish Cypriot vice president, and a 70/30 split in the civil service. In 1974, Greece (then under the control of a military Junta) backed a coup of the Cyprus government, leading Turkish officials to believe that a push for unification with Greece was imminent. Turkey consequently invaded the island, occupying the northern third. Thousands of military and civilian casualties were incurred by both sides, and hundreds of thousands of Greek and Turkish Cypriots were forcibly displaced from their respective regions. The island has stayed divided since the invasion, and Northern Cyprus unilaterally declared independence in 1983.

Yet the divided island, unlike other frozen conflicts, has since seen little violence. Since 2003, despite the partition, hundreds of thousands of Greek and Turkish Cypriots have crossed the Green Line, the UN administered border zone, each year. Peace talks for a unified state have been a constant agenda item for every UN secretary general since 1974, yet all have stalled. A unification referendum with nearly 90% turnout in both Cyprus and Northern Cyprus occurred in 2004 and was rejected overwhelmingly by Greek Cypriots and approved by Turkish Cypriots. Among the reasons cited for Greek-Cypriot rejection was the proximity of a united Cypriot state to Turkey. The most recent news regarding the reopening of Varosha, an abandoned Greek-Cypriot suburb in Northern Cyprus, is a product of a power struggle in Northern Cyprus that may have lasting impacts on the peace process as the repatriation of the suburb to its original Greek-Cypriot inhabitants is considered crucial for peace. At the time of writing, the Turkish Cypriot president Mustafa Akinci, a pro-reunification moderate, was tied in the polls with Ersin Tatar, the Turkey-backed prime minister of Cyprus. Both are contested to compete in a run-off election on October 18th, and Mr. Tatar, to gain votes among pro-Turkey Northern Cypriots, announced that his government would reopen Varosha. This is seen as a significant barrier to achieving a one-state solution. Yet should Mr. Akinci win, there may be a new catalyst for peace unseen in recent years – natural gas.

On February 8, 2018, Eni, an Italian oil company, announced a gas discovery in the Calypso field near Cyprus. The trillions of cubic feet of natural gas in Calypso offer Cyprus an opportunity to increase its energy independence while strengthening its economy, which has struggled since the 2008 recession. But exploiting the resource has proved to be difficult, as Turkey and Northern Cyprus reject Cyprus’ sovereign claims over its marine resources and therefore block the expansion of pipelines. These actions have pushed Cyprus into partnerships with Egypt and Israel, further reducing the likelihood of reunification. But Greek and Turkish Cypriot politicians could use the natural gas discoveries as a step towards forging peace. For instance, revenues from the sale of the resource could be used to provide an economic incentive for Turkish Cypriots to decouple their constitutional links with Turkey. Additionally, proceeds could also be used to raise money for the costs of reunification, ensuring no party feels they are taking on the financial burden. Greek Cypriots, who rejected reunification during the referendum, may feel that with the spoils of natural gas on the table, they have more clout in negotiations than before. Turkish – Cypriots, who backed reunification, may still do so despite less ties to Turkey as the economic incentives, powerful due to Northern Cyprus’ lack of internationally recognized status, will prove too large to ignore.

The complex and seemingly eternal nature of Cyprus indicates that should natural gas serve as a catalyst for a solution, it will do so only amid unprecedented diplomacy and cooperation. Yet the recent developments may still prove consequential; next time you read the news cycle, browse a little further to see how they have progressed.

Cover Image: “SVG map of Cyprus, Greece and Turkey”(2013), by Lfdder via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.