Two weeks ago I wrote an article about policies being formulated in some countries in Europe to resolve a long-standing crisis: the lack of women on boards of corporations. With studies showing little progress for women in this regard, many governments in the region are pushing for legislation which will require corporations to implement quotas. This however has re-ignited the debate on mandatory gender quotas. Critics question its efficacy and point out possible consequences that might emerge from such legislation, yet the lack of sufficient progress in hiring women in top level management suggests that such legislation is necessary. This article shifts focus from the debate in Europe and examines the same issue in the United States. It particularly looks at some of the key movements and studies involved in formulating policies to encourage increased presence of women in board rooms.

One of the newest movements in the United States pushing for gender equality in corporations is the 20% by 2020 Women on Boards Movement, led by a former CEO, Stephanie Sonneband, and a Public Relations Consultant, Malli Gero. The two women recognized the striking imbalance in boardrooms and decided to start a grass roots initiative to spread awareness of the issue amongst those who may have never thought about it: young individuals and middle managers in companies who do not have a diverse boardroom. As the name of the movement suggests, their mission is to increase the number of women on boards to 20% or greater by the year 2020.

One of the better established organizations promoting equality in boardrooms is the National Association of Women Business Owners (NAWBO). Established in 1975, the organization aims to promote a diverse environment in small businesses and corporations across the United States. Their greatest achievement was the creation of legislation H.R 5050 (1998) which no longer required women to have a male relative co-signer for business loans.

A third organization pushing for equitable representation in corporate leadership positions is Catalyst, a multi-national movement that wants to expand opportunities for women. It encourages this by producing research on a more equitable work environment. Recent studies have focused on the percentage of women in leadership positions across the country. The results of these studies echo the concerns of many who support diverse boardrooms: despite a gradual increase of women in leadership positions, the progress is too slow.

These organizations have taken part in and supported numerous studies in support of gender equality in leadership positions. Among the studies was a research led by the University of California Davis which found statistics indicating there are not enough women in leadership positions. Some of the key points are:

- There is only one woman for every nine men among directors and highest paid executives

- Only thirteen of the four hundred largest companies have a woman CEO.

- 44.8% of California’s companies have no women directors.

- By industry – software firms and those in Silicon Valley tend to include fewer women on the board. Firms in the consumer goods sector had the highest average percentage of women directors.

- Some of the best known companies in California – Apple, Google, Intel, Cisco, Visa, eBay, Yahoo! – had no women among their highest-paid executives at fiscal year-end.

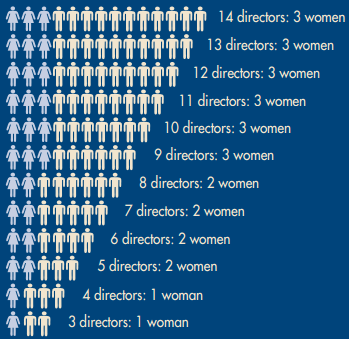

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/UCIrvine-Study.png” captiontext=”Minimum standards as per SCR-62: Courtesy of University of California Davis “]

Backed by leading women’s rights organizations, these findings played a crucial role in formulating one of the country’s groundbreaking resolutions, SCR-62, which pertains to public companies in California. The resolution points out that the government of California recognizes that a diverse board room is more profitable for a company and as a result there should be more women in top-level positions in public corporations. Though this resolution is not binding it has the potential of creating precedence for public companies in the United States by pointing to various studies which have shown a strong relationship between a more diverse boardroom and increased profits.

The causal link between a diverse boardroom and increased profits come from research like “Women Matter”, a study developed by Mckinsey and Company – a global management consulting firm. In 2006 and once again in 2010 the study researched over 300 companies worldwide in a variety of different fields and found that there was a positive correlation between the number of women in boardrooms and financial returns. In other words, companies with more women on their boardrooms had better financial returns compared to companies with no women at the top.

The studies also show that companies with more diverse boardrooms also had better organizational health – the satisfaction that employees gain from their organization. The study believes that a part of the answer lies in the “diversity of leadership behaviors that women can bring in corporations”. For example, men and women have different approaches to decision making. Men tend to be more individualistic and be better with corrective actions while women tend to be better collaborative decision makers and bring with them a holistic thinking (how decisions impact the environment, communities, employees, and etc.).

The third point of the study indicates that women are discouraged from pursuing top level management positions because many of them have preconceived views of certain jobs as not being for women and. Other factors include that women are “double burdened” with their job and their family responsibilities. Consequently, there needs to be more done to disprove these believes and better help women manage time between their families and work.

Closely related to the previous point is an important factor in determining whether future policies requiring gender quotas will facilitate the desired results. While the government may want to encourage companies to hire more women, women might be less inclined to pursue top-level management positions fearing the impact it may have on their family lives and consequently might not bother even applying for such positions. If this is true, then quotas will not have the desired effect. Policy makers encouraging gender quotas should thoroughly understand the underlying factors involved in the disparity between men and women in top-level management, and address them first before moving to legislated gender quotas.

At the end of it all policy makers should take the appropriate steps to determine objectively the causal factors in the lack of women in company boardrooms. This is after all a matter that can profoundly change global management ethics.