It is common knowledge that the world in its current stage of development would not be able to function without stable energy supplies. Oil and gas pipelines now crisscross the globe in much the same way as a cardiovascular system does in a human body. Countries possessing large supplies of natural gas and oil have an upper hand in the political and economic dialogues with other states. Countries heavily dependent on foreign energy supply often have no option but to comply with the wishes of their suppliers.

The energy relationship between the European Union (EU) and the Russian Federation is one of the best examples of the complexities of the supplier-consumer link. Russia currently stands as EU’s largest energy supplier, with several countries relying 100% on Russia for their gas supply. In 2013 alone, the newly built Nord Stream twin pipelines, laid under the Baltic Sea from Vyborg, Russia to Greifswald, Germany, carried 839 billon cubic feet of natural gas from Russian to EU consumers. The pipelines are each designed to carry a maximum of 1.9 trillion cubic feet (55 billion cubic metres) of natural gas annually. The Nord Stream project is a partnership of the Russian gas monopoly Gazprom, German Wintershall and E.ON SE, Dutch Gasunie, and GDF SUEZ Group.

EU has historically enjoyed a relatively stable energy relationship with the Soviet Union and then its biggest successor state, Russia. The peak of the relationship occurred in 2000, when the President of the EU Commission at the time, Romano Prodi, declared the goal of doubling EU gas imports from Russia. However, along with rising energy prices came rising tensions between the two sides. As the EU began to call for ‘security of supply’, Russia called for ‘security of demand’. The relationship worsened further when in 2006 Gazprom shut off the gas supply to Ukraine for failure to make timely payments and as a sign of political pressure. The shut-off threatened the entire EU supply as roughly 80% of European gas imports from Russia were transported through Ukraine.

As Ukraine had submitted its application to the European Union at the time, Russia felt geopolitically threatened by the potential proximity of Western borders; therefore, it used its monopoly on European energy reserve to advance its political goals. The relationship deteriorated further in 2009 when Russia refused to ratify the Energy Charter Treaty, which it had previously signed in 1994.

This deterioration in mutual understanding in issues pertaining to energy supply and demand has exacerbated the need for the EU to find new sources of energy and for Russia to establish new consumer markets. The EU has made a strategic attempt to locate and invest in new sources of energy, such as shale gas and solar power. It has also invested in finding new sources of natural gas, such as the Caspian Sea basin. However, such a diversification of supply centres on the availability and security of alternative transit routes, i.e. pipelines. Gas pipelines have become a geopolitical weapon used to control weaker states and ensure compliance. For example, as was mentioned above, when Ukraine expressed an interest in becoming an EU member in 2006, Russia promptly shut off the gas supply to the country, thus both cutting the supply to the EU itself and demonstrating to Ukraine just how economically and politically dependent the state was on its neighbour.

Although the EU has recently secured alternative gas suppliers from the Shah Deniz gas field off the coast of Azerbaijan to be carried through the Trans Adriatic pipeline, designed to transport a maximum of 350 billion cubic feet, by 2019, this supply is not nearly enough to replace Russian gas entirely. At the same time, Russia and the EU have recently agreed to let the Opal pipeline in Germany, a continuation of the Nord Stream pipeline, operate at full capacity, thus adding more Russian natural gas to the European market.

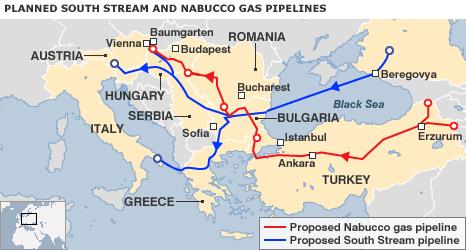

For its part, Russia has been actively involved in the South Stream pipeline and the Southern Corridor project in order to expand its hold on the European energy market and involve some of the more non-traditional states into the dialogue. The 2,400 km pipeline, which, according to Gazprom, will be fully operational in 2018, will be able to supply about 15% of Europe’s annual gas demand. The project is seen as Russia’s direct response to Europe’s attempt to find alternative sources of natural gas and as a countermeasure to ensure that the failed Nabucco pipeline project does not reappear on the debates table.

The South Stream pipeline will run through the Black Sea, Bulgaria, Hungary, Serbia, and Slovenia into Italy, completely bypassing the traditional transit point in Ukraine, and will transport 63 billion cubic metres of gas annually. The project has faced criticism of illegality from the EU and questions have been raised over its economic viability. Despite this, on January 29, 2014, three large companies, Germany’s Europipe, and Russian OMK and Severstal, secured the contracts to supply the first subsea portion of the pipeline. Europipe is expected to supply 50% of the pipes, OMK will supply another 35%, and Severstal will provide the rest.

As the South Stream pipeline and the Southern Corridor project are now a reality, the European Union has attempted to compromise with Russian Gazprom on the plan. The EU has encouraged the Energy Community, an EU policy group, to conclude a deal with Gazprom on the pipeline in order to avoid wasting resources on a project that does not comply with EU laws. One of the main concerns with the current plans as they stand is the fact that the treaties negotiated between the gas monopoly and the EU member states involved give Gazprom complete control, violating the bloc’s free-market laws. Ukraine has voiced its objections to the South Stream, despite being currently involved in a violent internal regime change, pointing out that the supply of gas from Siberia to Europe has not been affected by the unrest. The state sees the project as a serious threat to its status as a transit country as well as to its economic wellbeing, calling it ‘wasteful’ and ‘unnecessary’.

Thus, competing interests continue to be centre stage in EU-Russian energy relations as the Union seeks to reduce its dependence on Russian oil and gas and the Russian Federation attempts to expand its global market beyond the EU. Despite a historically stable relationship, recent developments support a trend of deterioration and mistrust. Many critics have called the South Stream pipeline Russia’s attempt to stifle the development of the Nabucco pipeline, which would have completely excluded Russia. Some have also pointed out that laying a pipeline under the Baltic Sea is highly environmentally dangerous as it disturbs the natural habitat of numerous marine species. While its supporters have claimed that South Stream has drawn Russia and the EU closer together, forcing them to resolve outstanding issues, others feel that the South Stream project has reintroduced issues of mistrust, as some EU states feel excluded. While both Russia and the EU seek to address the various issues of their domestic energy markets, they will undoubtedly remain each other’s biggest energy partners for the foreseeable future, bound by the abundance of pipelines crossing their territories.