(Editor’s note: This piece comes from our friends south of the border at the Center of International Maritime Security. As we Canadians spend so much time focused on American foreign policy (often at the expense of our own), it’s always a treat to see an American perspective on Ottawa’s affairs.)

For nations with a global outlook, the ability to respond to contingencies around the world has often been a mix of necessity and choice. Nations dependent on overseas trade or empires for their livelihood have found it a requirement to establish on distant shores the means to protect their prerogatives. Such foreign footholds have proved no less useful to nations that choose to pursue active foreign policies driven by humanitarian, religious, ideological, or expansionist aims. Imagining a country that requires extra-territorial basing for both reasons likely doesn’t conjure up images of moose and ice hockey, yet 21st-century Canada definitively qualifies on both counts. And it’s got a plan to secure that capability.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”320″ imgsrc=” http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vo7/no3/images/Ward-4.jpg” captiontext=”A Canadian in the Caribbean: Haiti, 2010.”]

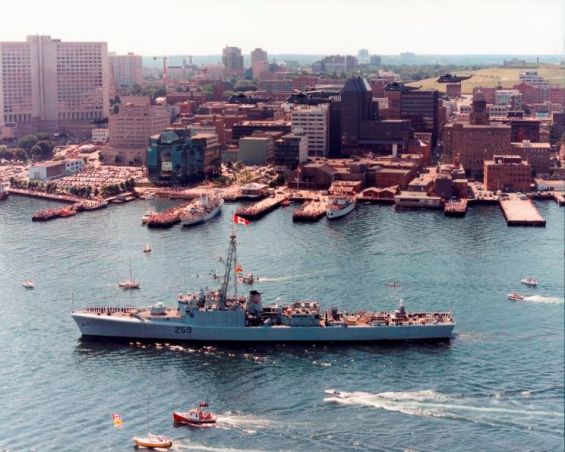

Canada is a maritime nation. While admittedly three quarters of Canada’s trade is still with the US, 20% of that travels by sea – as does 97% of the rest. However, it’s Canada’s foreign policy choices and commitments that make it stand out as a truly global nation. In the past decade alone Canada has been involved in combat and peacekeeping operations in Afghanistan and Libya, counter-piracy missions off the Horn of Africa, non-combatant evacuation (NEO) operations in Lebanon, and humanitarian assistance/disaster relief (HA/DR) in Haiti. The experiences of the new century have left a legacy of lessons the government is eager to leverage.

In 2008, Canada’s military set out to determine how it could quickly and efficiently ratchet up to full-scale crisis operations in the far-flung corners of the globe, yet do so in a manner befitting Canada’s fiscal and resource realities. The solution hit upon in 2010 was a constellation of “operational support hubs,” to be established in up to seven worldwide locations where existing transportation facilities and infrastructure could support a contingency influx of Canadian troops and logistics. Four C-17 Globemasters acquired by Canada’s armed forces in 2007 provide the rapid airlift capabilities while the storage facilities nearby will be rented to preposition equipment.

In tangible terms the plan really requires only a few dedicated personnel stationed at each port to maintain relationships, monitor the conditions of the facilities and equipment, and act as advanced husbanding agents in the event of a crisis. The heavy lifting is the advanced diplomatic work of brokering the deals. So far Canada has three deals in hand: Kuwait has agreed to act as an intermediate staging terminal allowing up to 3,000 troops, Germany is making available a portion of the Cologne-Bonn International Airport, and Jamaica has signed up for a yet-to-be-named location. Additionally, Singapore has been mentioned as a likely location, which would accord with its recent granting of foreign basing rights to others. There has been more difficulty for Canada in securing an agreement in Africa, as some reports indicate an East African hub (in Kenya or Tanzania) has run into the same fears of colonial permanence that sent the US military’s AFRICOM HQ to Stuttgart, Germany. A West African hub may prove more welcoming, as other reports also suggest unnamed potential hosts look forward to possible training opportunities, but that would bring the count only up to five and leave ready access for counter-piracy missions in the Indian Ocean noticeably lacking.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”320″ imgsrc=” http://freepages.military.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~cdobie/berbeck-scan00321.jpg” captiontext=”“Don’t mind us miss, we’re with the advance team, just making the sure the beaches are suitable…””]

Despite the political uncertainties (including the potential that a host government could always renege on its agreement if the crisis issue was domestically too sensitive), the “Maple Leaf Model” of basing agreements and power projection may prove ideal for many nations in the new century. It’s debatable whether countries today have more or less active foreign policies than they did, say, 100 years ago, but in the age of globalization few are without important, if not vital, interests abroad – and in many cases, overseas. The more familiar model of permanent, fully staffed, made-to-order facilities is impractical for the great majority of countries to affordably cover their bases, so to speak. The US model, which mixes such bases with armadas of prepositioned equipment and its own mobile bases, aircraft carriers and amphibious ships, is even less so. The small footprint, low costs, and opportunity for increased diplomatic ties of the Canadian way should be attractive to the many countries that want to maintain an ability to protect their interests abroad and conduct an active foreign policy.

It is possible there may be a first-mover advantage as nations that have already signed agreements with a one or two “active” powers may not want to risk a domestic backlash against “appeasing foreigners,” but it is just as possible a few host countries may decide to make an industry out of their perceived logistical and situational attractiveness and market their services to a broad swath of interested nations. Time will tell the extent, but expect to see other nations follow in Canada’s footsteps, if not moose tracks.

LT Scott Cheney-Peters is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve and the former editor of Surface Warfare magazine. He is the founding director of the Center for International Maritime Security and holds a master’s degree in National Security and Strategic Studies from the U.S. Naval War College.