Relationships with nations across the Atlantic Ocean have significantly shaped Canada’s foreign policy, as well as its role in NATO. Historically, the most influential European nation is Britain, whose colonial and constitutional legacy contributed to a sense of shared history, culture and ideology in Canada. Beyond Britain, Canada developed links, often through immigration, to other European states with the same effect. Similar factors in the United States and in Europe have cultivated acceptance of the quasi-philosophy of Atlanticism, which emphasizes the necessity and desirability of close cooperation between North America and Europe, in the pursuit of mutual security and prosperity. Atlanticism forms the conceptual foundation of North America-Europe relations upon which the post-war North Atlantic system has been built.

Despite its prevalence, Atlanticism in its modern form is a relatively new mindset. Outside of Canada’s ties to Britain, it only began gaining in strength around the Second World War. Prior to the war, Canada limited its direct involvement in Europe, preferring bilateral interactions with either Britain or the United States. As mentioned, Canada’s relationship with Britain tied it to the latter’s worldview. This did not necessarily translate into close affiliation with other European countries. Closer connections with the United States also discouraged the development of Canada-Europe links. Not only was the US itself an isolationist power for most of its history, it also satisfied most of Canada’s needs, thus making ties to Europe redundant.

During and after the Second World War, however, Canadian transatlantic relations underwent a significant change. Wartime cooperation played a major role in the development of new transatlantic relationships and independent Canadian participation in the Marshall Plan solidified goodwill amongst Atlantic nations. Most importantly, the development of the Cold War and the threat of the Soviet Union necessitated a close North Atlantic relationship. Eventually, transatlantic political, economic and security ties were formalized by the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty in 1949, as well as various other Atlantic institutions, cementing the dominance of the Atlanticist view for at least the next half century.

In order to maintain its position as the focus of Canadian foreign policy, the necessity and desirability of transatlantic cooperation must be emphasized.

Atlanticism’s dominance arose due to a convergence of interests amongst Atlantic nations, principally the desire for the preservation of European independence through economic reconstruction and security assurances. To maintain this status, Atlanticists have encouraged transatlantic collaboration in political, military and economic spheres, and, in general, these efforts have been successful. Politically, democratic societies have flourished in North America and Europe and the “West” remains relatively cohesive. Militarily, NATO has represented a comprehensive military alliance for the past 65 years. Finally, building upon already close commercial ties, the signing and ratification of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the EU, and the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), between the USA and EU, would mark significant victories in the effort for Atlantic economic cooperation. Even Atlanticist language has entered common usage— “across the pond” evokes a sense of neighbourliness, despite the vast distances in question.

Atlanticism, however, faced some formidable challenges in the past and will continue to be criticized in the future. Before the Second World War, the strongest argument against the Atlanticist view came from the Continentalist conception, a theory that traditionally emphasizes closer relations with the United States to the detriment of Canada’s relationship with Britain (or Canadian independence). Moderate Continentalists argued that over-dependence on Britain weakened Canadian identity and that the United States was in a better position to help Canada. Radicals argued for varying degrees of integration with the United States, from customs unions to annexation. Continentalism’s successes include the close relationship Canada now shares with the US, as well our many linking institutions, including NAFTA. Paradoxically, after the Second World War, Continentalism in Canada actually contributes to Atlanticism, as Canada is more likely to emulate the US Atlanticist foreign policy.

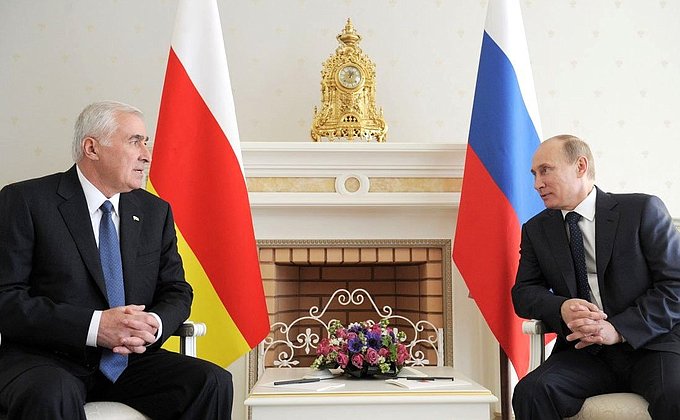

It is in Europe, not Canada, that Continentalism poses the most potent challenge to the Atlanticist view. For the most part, opposition to closer transatlantic ties derives from a desire for the preservation of a distinct European or national identity. Many Europeans have fought against Atlanticism on the basis of a perceived threat of cultural “Americanization”. These fears are not without justification— Canada also struggles to differentiate itself culturally from the United States. In addition, Atlanticism suffers from persistent military neutrality in European states and concern for the fragile relationship with Russia. A recent article in Foreign Affairs, argued that a proposal for Swedish and Finnish membership in NATO would have the added benefit of joining two strongly Atlanticist states to the Alliance. This implies a possible deterioration or stagnation of commitment to Atlanticist institutions, especially to NATO, amongst other European states.

Another conception, outside of Europe, is challenging transatlantic cooperations as the focus of Canadian foreign policy. This is the new and increasing emphasis placed on the Pacific region by Canada and the United States. Coinciding with Barack Obama’s ‘pivot’ to Asia is a similar though less militarized course charted by the Conservative government. As part of a plan to enhance economic associations with emerging markets, Prime Minister Harper has committed significant resources to strengthening ties with Asian countries, particularly China. In 2012, for example, the Canadian government concluded a landmark trade deal with the People’s Republic. A shift of the centre of economic and political activity eastward will no doubt draw attention to the Pacific region, thereby weakening Atlanticist ideas. With limited resources, politicians may eventually be forced to choose between these two regions.

Atlanticism’s dominance is therefore threatened on two fronts. In order to maintain its position as the focus of Canadian foreign policy, the necessity and desirability of transatlantic cooperation must be emphasized. Atlanticism has a strong foundation to stand on, including deep cultural, historical, and economic connections. Recent conflict with Russia has also sparked reaffirmations of North Atlantic unity in the face of aggression. Finally, there are continuing drives for stronger economic links to revitalize flagging economies in both Europe and North America. Atlanticism still serves a purpose and Canada’s interests remain far more aligned with their partners across the Atlantic than with rising powers in the Pacific. If Atlanticists can maintain the convergence of interests that brought their philosophy to prominence, Atlanticism will continue to play a dominant role in Canadian foreign policy.