Roughly $5 trillion in global trade passes through the resource rich South China Sea (SCS) annually, making it of immense interest of regional actors – China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Brunei – to maintain control over their maritime territorial holdings. This article will focus on Vietnam, China, and the Philippines because of the severe contention of past interactions.

China has constructed seven artificial islands on reefs in the SCS beginning in late 2013. The Asian Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) has closely watched this reclamation activity, detailing satellite photographs of the construction. It has observed China’s construction of various military facilities on these islands, which includes airstrips on the Fiery Cross and Subi Reefs, and anti-aircraft and naval guns on Gavin Reef. A 2015 Pentagon report outlines the land reclamation efforts of regional actors, with 2,900 acres reclaimed by China, 80 acres by Vietnam, 70 acres by Malaysia, 14 acres by the Philippines, and 8 acres by Taiwan.

In 1974, a violent naval skirmish erupted between China and Vietnam in the Paracel Islands, resulting in the death of more than 70 sailors. China then proceeded to seize the islands from Hanoi. In 1988, another naval engagement occurred between these two states over the Johnson South Reef in the Spratly Islands, resulting in 64 Vietnamese sailors’ losing their lives. In December 2016, Vietnam reportedly began construction on Ladd Reef in the south-western fringe of the Spratly Islands, in what seems like a response to China’s intensified land reclamation efforts. Greg Poling, Director at AMTI, claims the Ladd Reef could defend Vietnamese-held Spratly Islands nearby. Trevor Hollingsbee, a retired Naval Intelligence Analyst with the British Defence Ministry, adds this construction is an effort to “fix vulnerabilities” like the outpost on Ladd. These efforts follow further fortifications in August, when Vietnam placed mobile rocket launchers on several islands.

In 2012, China and the Philippines engaged in a maritime standoff at the Scarborough Shoal, which China would effectively seize. The shoal is located 120 nautical miles (nm) off the coast of the Philippines, within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) which grants coastal states sovereign rights over resources up to 200nm beyond its territorial coast. The Philippines under former President Benigno Aquino III initiated an arbitration under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) against the People’s Republic of China in January 2013.

The arbitral tribunal of the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled on July 12, 2016, that China’s claimed historical rights in the SCS represented by the “Nine Dash Line” (NDL) was invalid. China boycotted the proceedings calling them “ill-founded,” adding that it would not be bound by the ruling. The NDL is a demarcation line that includes the Paracel Islands, the Spratly Islands, and the Scarborough Shoal. Some analysts have called this a “strategic triangle” within which China is working to project its regional influence. If China expands construction on the Scarborough Shoal, it will get closer to bringing the region under its influence, though at the risk of significantly escalating regional tensions.

President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines took office in June and has taken steps to mend relations with China, to the detriment of previously strong relations with the United States. In a state visit to Beijing in October, President Duterte openly denounced relations with the U.S., announcing “my separation from the United States.” Additionally, he has favoured relations with China at the cost of international law, stating in December that “I will set aside the arbitral ruling. I will not impose anything on China.” President Duterte’s pro-China and anti-U.S. stance seems to demonstrate greater bilateral ties between the two regional powers excluding the U.S. from regional dialogues.

In return, China recently eased tensions with the Philippines over the Scarborough Shoal, granting Filipino fishermen access to fishing grounds they were prevented from accessing since China seized the shoal in 2012. In addition, the Philippines’ Foreign Minister, Perfecto Yasay, told reporters that “President Xi has promised President Duterte that China will not reclaim and build structures on the Scarborough Shoal,” a promise made during the official visit in October, after the topic was raised “in response to U.S. intelligence reports suggesting China was sending dredging ships to the area.” Poling warns however, that this is not a big difference, and “without a formal agreement over continued access to Scarborough, Beijing’s current accommodation looks more like a temporary olive branch to the Duterte government.”

In January, China and Vietnam issued a communiqué proposing negotiations on regional maritime disputes, towards “enhancing mutual trust, strengthening the traditional friendship, and deepening the comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership between the two nations.” Denny Roy, Senior Fellow at the East-West Centre, states this demonstrates “China’s effort to neutralize opponents around the South China Sea by working things out with them on a bilateral basis rather than via a group of countries where it would be a weaker party.”

The important consideration from this discussion is that eased tensions could escalate depending on whether artificial islands continue to be constructed and fortified. Central to this is whether China builds on the Scarborough Shoal, which would greatly escalate tensions with Vietnam. Moreover, détente with Manilla is not guaranteed. Indeed, despite Chinese reassurances, the Philippines’ foreign minister at a January AESAN meeting expressed his concern that China is continuing its militarization in the Scarborough Shoal which led to the cancellation of an official Chinese visit to the Philippines.

Regional contention also depends on how regional powers proceed, and whether other states begin construction on their territorial holdings, similar to Vietnam at Ladd Reef. This could cause other states to build and fortify their territorial holdings to deter other regional actors from taking them. Continued fortifications of artificial islands will only heighten the ongoing security dilemma.

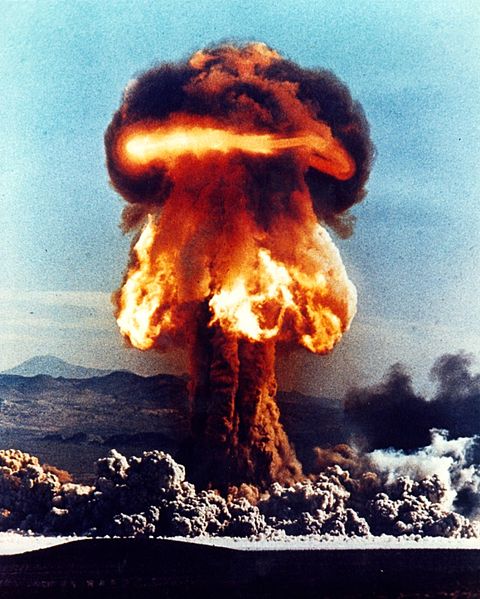

Photo: Chinese construction at Subi Reef part of the Spratley Islands located in the South China Sea via wikimedia commons. Public domain.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.