A popular interpretation has emerged in 21st century international politics that we are on the cusp of radical changes to the global order, changes that will particularly favour the developing world in and, in terms of power structures, will be decidedly more multilateral. For believers of this narrative, the formation of the BRICS political bloc represents the movement towards a diffused global power structure with a united voice from the world’s leading emerging markets. It hasn’t quite lived up to the hype initially generated at the group’s first summit in Yekaterinburg, Russia in June 2009.

Part of this disappointment can be explained through the history of the BRICS founding. The grouping started out as an economic acronym referring to the economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China before South Africa was invited to the political bloc in 2010. The acronym was first coined in a 2001 Goldman Sachs paper written by Jim O’Neill, then head of Global Economic Research. O’Neill raised the profile of emerging economies by calling attention to their projected GDP growth. He correctly predicted that over the course of the next 10 years, the weight of Brazil, Russia, India and especially China in world GDP would grow, raising important issues about the global economic impact of fiscal and monetary policy in the BRICs. O’Neill concluded by suggesting that as the BRIC economies became more integral to the global economy, world policy-making forums should be re-organized to incorporate BRIC representatives.

Except for the fact that they are all emerging economies, what do these nations have in common that gives them political affinity?

The paper received worldwide attention, but with the War on Terror just gearing up, and a lack of global economic crisis, there was little traction from the industrialized world to take up O’Neill’s suggestions on BRIC incorporation. The paper inspired the foreign ministers of the BRIC nations to meet informally on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in September 2006, which subsequently led to the official annual summits that began in 2009. O’Neill was just as surprised as the rest of the world at the development, saying to CNN “Who would have ever dreamt that there would be a BRIC political club? It certainly isn’t something that I ever imagined.”

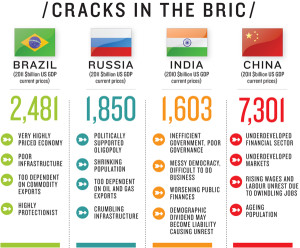

And why would he? Except for the fact that they are all emerging economies (Russia currently a submerging economy), what do these nations have in common that gives them political affinity? India, Brazil and South Africa have strong democratic institutions, while China and Russia are autocratic. In addition, the bloc lacks a unified vision of overhauling international institutions like the United Nations Security Council. Both China and Russia hold permanent seats, but have shown little interest in supporting the aspirations of India, Brazil and South Africa to also hold permanent seats. Competition is rife amongst the bloc, as was evident in the April 2012 vote for a new World Bank President. The BRICS were not able to build consensus by uniting behind a single candidate.

Then there is the sticky wicket of economic size. China’s economy is more than $1.5 trillion larger than the combined economic output of the other four BRICS members. O’Neill recently commented that if he had to dream up the acronym again, he would probably just call it ‘C’. On the other end of the spectrum is South Africa, whose economy with a GDP of $390.9 billion last year doesn’t even come close to the trillion dollar economies of the other four, further highlighting the asymmetry in the group. At the 2013 BRICS summit in Durban, South Africa, the BRICS leaders announced that they had agreed to set up a development bank, one that could challenge the influence of the Bretton Woods institutions. Never mind challenging the IMF and the World Bank, the BRICS development bank would also have to compete with the China Development Bank which between 2008 and 2010 outstripped World Bank lending by $10 billion.

Nevertheless, the announcement gave hope to followers of the interpretation that a new global order is being restructured by the developing world. In the talks that have followed, it’s clear that the economic disparity of the members will pose an impediment to the banks setup. The finance ministers of the BRICS bloc have agreed on an initial start-up capital of $50 billion to be increased to $100 billion in five years time, but there has been no agreement yet on each country’s share in the bank’s structure or where the bank should be located. The commitment would be a financial strain for many members who, with the exception of China, are suffering from sluggish growth and currency shocks.

The underlying issue preventing the BRICS bloc from becoming a global force in reshaping the world order lies in what grouped these countries together in the first place—being emerging markets. A defining characteristic of any emerging market is the centrality and often domination of political forces over economic fundamentals. In other words, the domestic politics of the BRICS members trumps aspirations at building a new world order. Brazil, India and South Africa are all holding key elections this year, while China remains focused on its domestic reform agenda, and then there’s Russia, where the Kremlin’s recent actions in Ukraine have focused all its attentions.

So if not the BRICS, then who? Jim O’Neill recently coined a new acronym for a BBC series titled the MINTs (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey). It prompted some to ask whether they could do what the BRICS have not to mold a multilateral world order. In short, the answer is no, because just like the BRICS, domestic politics will prevent them from seriously engaging in world order building. It also applies to the CIVETS, MIST, and any of the other alphabet-soup acronyms that are floating around. International political blocs need more than a catchy name; they need common values, consensus, a shared vision, and most importantly the political capital to build that vision.