Last December (2015) representatives and leaders from countries around the world gathered in Paris for the 21st Conference the Parties (COP21) to discuss a renewed global climate change accord. The summit set out to develop collective program frameworks for sustainable development in order to limit global temperature increases to 2C. The result was the comprehensive Paris Agreement, signed by 180 parties, including Canada. The agreement requires that at least 55 parties to the convention accounting in total for at least 55% of the total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions ratify the agreement for it to come into effect.

Five months ago, on April 22, world leaders met again at the UN headquarters in New York to open the Paris Agreement for signature and their instruments of ratification. Prime Minister Trudeau spoke before the the UN General Assembly at the conference and reaffirmed Canada’s commitment to climate change saying, “Canada believes that climate change presents a challenge that must be overcome.” Citing Canada’s investments in low carbon economy funds and clean tech research and development, he declared that Ottawa had begun to rise to the “daunting challenge” that lies ahead.

Despite his optimism at the conference, Prime Minister Trudeau has encountered difficulty implementing these new environmental policies. Ottawa has had difficulty finding consensus among provinces and territories on the best ways to curtail carbon emissions and set targets. In March prior to the New York conference, the Prime Minister, provincial, and territorial leaders met at the first ministers’ summit in Vancouver to discuss a climate change plan. Some premiers and territorial leaders expressed concern over what some viewed as the federal government imposing a carbon price plan on them. The summit document, the Vancouver Declaration, stated that different approaches to carbon pricing could be used by each province and territory as a part of the solution, but did not outline more precisely what approaches would be used.

According to the United Nation Framework Conventions on Climate Change (UNFCCC), as of September 7, 2016, only 27 of the 180 signatories at COP21 have formally ratified the document and brought carbon-emission reduction targets into their domestic law. The lack of consensus on a climate change action plan within Canada has meant that thus far, the country has been unable to ratify the Paris Agreement and begin working towards its targets. The Prime Minister, provincial, and territorial leaders only have until April 21, 2017 to ratify the agreement.

On September 3, 2016, China and the US formally ratified the Paris Agreement. China, a developing country, pledged to reduce its emissions by 60% to 65% per unit of its 2005 GDP output by 2030. The US has committed to decrease its GHG emissions 26-28% below its 2005 levels by 2025. Collectively, the US and China account for 38% of global GHG emissions, bringing the Paris accord closer to meeting the minimum participation of 55% of the world’s GHG emitters for it to come into effect.

Irrespective of the involvement of these big emitters, Canada still has a moral and political obligation to formalize its participation and meet its target. Canada is the ninth largest GHG emitter, and contributes 1.6% of global emissions. Canada is also a large GHG emitter per capita; in 2011 Canadians emitted 16.24 metric tonnes of CO2 emissions per person. If Canada wants to demonstrate a commitment to tackling climate change, it is necessary that Canada ratify the agreement.

At COP21, Canada pledged to reduce its emissions to 30% below 2005 levels by 2030. Canada’s targets are close to other developed countries’ targets declared at the summit. For instance, New Zealand, a small developed country, set its targets to reducing GHG emission by 30% from 2005 levels by 2030. Comparatively Norway was a bit more ambitious and set its targets to reducing 40% of its GHG emissions from 1990 levels by 2030.

Canada has also demonstrated some financial commitment in the fight against climate change. At the Paris conference, Canada pledged $300 million dollars to Mission Innovation for clean technology development. It also promised $2.65 billion dollars for emissions-reduction projects for developing countries. On the provincial level, Ontario pledged $8.3 billion dollars over the next five years on measures to curtail Ontario’s emissions of GHG. But Canada’s targets are also ambitious, and require that Canada reduce its emissions by 208 million tons, a feat that according to Parliamentary Budget Office is equivalent to taking all gasoline and diesel fueled vehicles off the road. Meeting these targets will require all sectors of the Canadian economy to strongly commit to “clean” practices.

If Canada wants to be a respected leader in climate change, it is important that it ratify the Paris agreement before April 21, 2017, which means that the Canadian government and its provincial counterparts will need to make environmental policy a top priority in coming months. Climate change is a collective action problem, yet provincial and territorial leaders are having difficulty agreeing on ways to lower GHG emissions. Settling these differences could provide an opportunity for Canada to become a global leader in environmental policy.

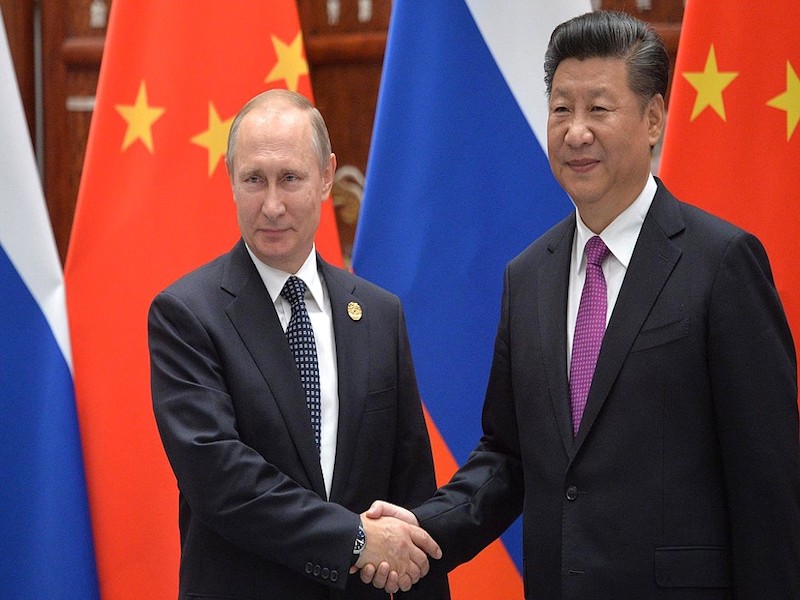

Photo:Prime Minister and Premiers at COP21 in Paris, (2015), by Province of British Columbia via Flickr Licensed Under CC some rights reserved

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.