On 4 August 1914, the First World War erupted as the German Army marched through neutral Belgium on their way to Paris. The British Empire, bound by treaty, declared war on Germany and four and half years of industrialized carnage ensued.

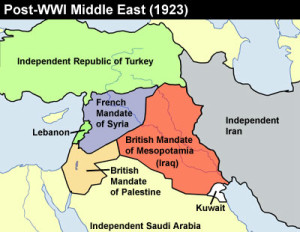

Yet the lamps of Europe, to borrow the phrase of British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey, were not the only ones to be extinguished by the dreadful spectre of a worldwide war. The Middle East, under the Ottoman Empire, a Germany ally, was as much a battleground as the muddied trenches of France and Flanders. Across Palestine (Israel), Mesopotamia (Iraq), and Persia (Iran), Britain and Russia battered the Ottoman Army until Constantinople, left on the brink of bankruptcy and widespread starvation in Anatolia, sued for peace in October 1918.

And today, the consequences of the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire ring loudly. In Gaza, Palestinians continue to fight for self-determination. In Syria, sectarian strife has brutalized the Syrian people for over three years. In Iraq, the Kurds, who are at the moment the only viable bulwark against the Islamic State’s expansion, remain stateless.

Without the First World War, the Balfour Declaration would not have been declared and Palestine might today be a state, not a dream. Written on 2 November 1917 by British Foreign Secretary Sir Arthur James Balfour to Lord Rothschild, a principal backer of the British Zionist Federation, Balfour communicated that the British Government viewed ‘with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people’. A shrewd political manoeuvre done to appeal to American Zionists, who would in turn put pressure on the American Government of Woodrow Wilson to commit more fully to the Allied war effort, and to encourage Russian Jews to pressure the Bolsheviks into returning to the war, the Declaration laid the groundwork for over two decades of Jewish emigration to Palestine, the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine in 1947, and the eventual creation of the state of Israel.

Without the First World War, Syria, plagued today by sectarian strife and almost unimaginable violence, might also look different. From a loose conglomerate of Ottoman sanjaks and vilayets – an administrative system akin to provinces and territories – Syria was transformed into the Arab Kingdom of Syria in March 1920. The Hashemite Prince of the Hejaz, Faisal ibn Hussein, was declared its king, and the Syrian National Congress, a parliamentary body, was convened. However, Arab-Syrian democracy did not mesh with France’s foreign policy of colonial expansion and what can only be described, albeit retrospectively, as an absurd sense of irredentism; the belief that Syria and Lebanon were tied inextricably to France by the medieval crusades. Ignoring its own promises of Arab self-governance, France invaded Syria, occupied Damascus, expelled Faisal and Arab-Syrian nationalists, and replaced the Syrian Parliament with a League of Nations Mandate for Syria and Lebanon.

Without the First World War, Iraqi Kurds might today have their own state. Emboldened by the Anglo-French Declaration of November 1918, which promised the peoples of the Middle East ‘the setting up of national governments and administrations deriving their authority from the free exercise of the initiative and choice of the indigenous populations’, Iraqi Kurds believed mistakenly that self-governance was on the table for them, too. Yet Britain had little interest in segregating its newfound possession, the League of Nations Mandate for Iraq, and in the process losing the oil-rich fields of Mosul. So the Kurds revolted and declared the short-lived Kingdom of Kurdistan in September 1922, which was brutally suppressed by Britain in a series of aerial bombings that included even the use of mustard gas. By 1924 British bombings had pummeled the Kurds into submission. They surrendered to Britain and were subsequently reincorporated into the Kingdom of Iraq.

True, explaining away the problems of the modern Middle East by invoking the First World War is in some ways an illusory panacea, a reduction of twentieth- and twenty-first-century international politics to a single, hundred-year-old event. But much more than the titanic struggle against Nazi Germany during the Second World War or even the half-century chess game of Western powers meddling in Middle Eastern affairs during the Cold War, the First World War reshaped boundaries, gave birth to new states, and crushed the national aspirations of some who are still searching for sovereignty today.

As both Europe and North America commemorate the beginning of the ‘war to end all wars’, the current state of affairs in the Middle East reminds us that the First World War’s lasting shockwaves still shake that troubled part of the world.