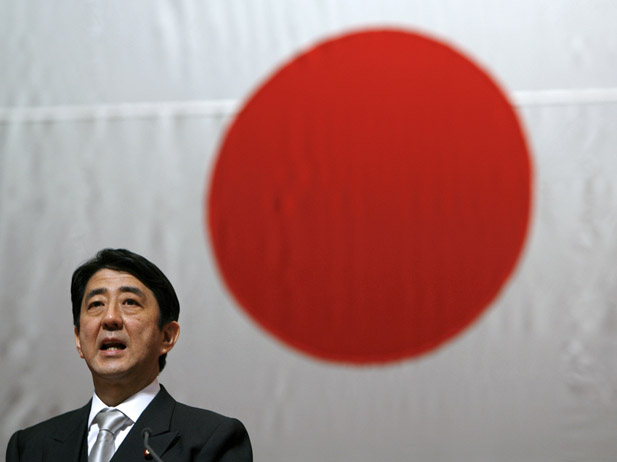

Shinzo Abe, Japan’s Prime Minister, has spent trillions of yen in the past few months as part of his economic strategy. This past January, he announced the implementation of ‘Abenomics‘, a “three-arrowed booster plan” financed by the country’s quadrillion-yen sovereign debt. In his commendable and so-far partially successful attempt to bring the economy out of its two-decade deflationary slump, Abe made the country’s debt an issue that cannot be ignored. It’s time to pay, with interest.

The Financial Statement

Abenomics, put simply, consisted of: 1) printing trillions of yen and buying back bonds to increase the money supply, 2) spending trillions of yen as part of a fiscal stimulus, and 3) bankrolling incentives to increase investment and consumption. In tandem, these policies will ideally help Japan reach its 2% inflation target, an ambitious goal given the country’s proven resilience to inflation.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://mediaserver.fxstreet.com/Reports/ec9a150d-8773-45c5-988d-d8a08a4fb198/infiation_20130522110612.jpg” captiontext=””]

The Prime Minister’s strategy has significantly strengthened the economy, which has entered its third consecutive quarter of growth. The Nikkei is stronger and the exports are a big contributor to the recent growth spurt. In its most recent economic report, the government announced that “recent price developments indicate that deflation is ending”, a bright outlook given the two decades of almost continuous negative inflation.

However, Japan’s government knows it cannot continue to fund good intentions with the country’s debt. Already burdened by a deficit equivalent to 300% its GDP, the country can only justify the stimulus if the economy can sustain the recent growth rate. Unfortunately that does not look like the case. Projected annual GDP growth has already slipped from 4.1% to 2.6% since June, which worries investors and consumers alike.

Credit Limit Reached

Japan’s debt was an issue long before Shinzo Abe began his second term as Prime Minister and implemented the reforms. In fact, Abe’s predecessor already had a strategy in place to tackle it: raising taxes. As it stands, the plan would double consumer taxes over the next two years: from 5% to 8% by April of next year and then to 10% by October of 2015.

In fact, the tax will be complimented by drastic fiscal cuts. Abe has promised to slash the annual deficit by ¥17 trillion, while avoiding further debt issuance. The details of how this is to be done remain cloudy and cause the G7 to question Japan’s commitment to addressing the debt, especially since the Bank of Japan is expected to increase its monetary stimulus further in the next year.

Unwilling Financers

The problem with implementing this tax plan goes beyond consumer discontent. Spending cuts combined with tax hikes could negate the progress that Japan made in the past couple of months. The question is: does the economy has enough growth momentum to withstand it?

Some analysts say a 3% increase alone would contract GDP by 1%, without taking into account knock-on effects or the subsequent 2% hike. For a country with a projected growth rate of 2.6% per annum, this could spell another deflationary spiral.

The outlook is bleak partly because Japanese companies have not bought into Abe’s economic strategy. They still await labour and land reforms that address their main concerns when investing, but they are not in sight. Abe’s reluctance to reform these sectors caused projected investment for the year to fall by 0.4% and capital investment to enter its sixth consecutive quarter of decline with a 0.1% decrease.

Ironically, it is the wealthy and the big companies who have expanded profits and benefited from Abenomics, but a sales tax will hit all bank accounts. Even though Abe enjoys substantial popular support, a tax will really test his supporters’ commitment and loyalty.

Taxes have never been well received by the Japanese. The American implementation of the first value added tax, during the occupation at the end of World War II, created a deep resentment of the policy. It was quickly abolished, but when a consumer tax was introduced in 1989, its reception was less than enthusiastic. Since, sales taxes have only been raised twice by mild 2% increments, but have faced severe public disapproval. The second increase is sometimes blamed for the 1997 slump, even if other economic forces were also at work.

Historically, the Japanese have been savings-oriented, which explains the economy’s resistance to inflation. The saving rate has steadily declined in the past few years in favour of consumption, but maintaining a steady level that will fuel the economy is a difficult task. The tax plan will only add to the challenge. As people see their disposable income decrease because of the levy, they will save in anticipation of a tough period ahead. In turn, the decrease in consumption may cause deflation and increase the value of the yen, sparking a decrease in exports. If households cannot absorb the tax and overall private consumption falls significantly, the country might fall into a third ‘lost decade’.

Reworking the Repayment Strategy

Monetary easing and fiscal spending alone are not a sustainable approach to growth. Investment and consumption are necessary for the economy to survive, especially when facing a tax shock, but neither is strong enough to fully counter Japan’s deflationary pressures. Abe must be very careful not to stifle the country’s fragile progress with a badly timed levy.

The government desperately needs the extra revenue, but the Prime Minister must still decide if the 3-point increase in the sales tax is the best option. He has convened international expert panels to discuss the effects and alternatives of a tax hike -including the potential for a more gradual and flexible 1% per annum increase- but his options are limited.

In light of the recent favourable –if slowing- economic indicators, increased pressure by the G7 to balance the debt, and the internal insistence to address the deficit, Abe will be effectively unable to resist a levy.