Part I of the series can be found here.

Turkey’s domestic terror policy leaves no question regarding its opinion of Kurds. The government’s reasoning for maintaining a strict terrorism policy appears to be founded in valid concerns; ISIS is directly on Turkey’s southern border and the PKK has resumed attacks on security forces following the collapse of a two-year cease-fire last summer. So far in 2016, Turkey has endured five deadly attacks in major cities.

Despite these threats, recently the Turkish state’s definition of terrorism has broadened beyond reason. The term “terrorism” now refers to making statements the Turkish government doesn’t agree with. The government’s liberal definition is consistent with its ever-increasing authoritarian behaviour and has more serious consequences than repressing freedom of expression.

Since the end of a cease-fire between the Turkish state and the PKK in 2015, the fighting has expanded into the region’s urban centers, and extensive collateral damage has become the standard once again. Human rights organizations have counted hundreds of new civilian deaths since last summer, adding to the approximately 40,000 total in this protracted conflict. The government’s newest trick is to label these civilians as terrorists, allowing them to leave the deaths uninvestigated, label the casualties as militants (and therefore legitimate targets) and maintain that only terrorists have been targeted.

The Turkish state relies on its involvement and importance in fighting ISIS as legitimation for a harsh terror policy, even as it lends support to those NATO deems as terrorists while increasingly targeting its own civilians. Turkey’s terror policy is not only problematic to the fight against ISIS for NATO and the EU, but also overlaps with other issues posed by Turkey, particularly its role in addressing the ongoing migration crisis in Europe.

This month, a visa-free travel deal between Turkey and the EU almost collapsed after Turkey refused to meet one of the EU’s five key conditions out of a larger set of 72 criteria. The European commission made its offer conditional on Ankara rewriting its anti-terrorism laws because of their repressive and fatal effects on Turkey’s Kurdish population.

Turkey’s vehement refusal to change its laws demonstrates the way in which the various challenges it poses are inextricably related. The EU cannot do without Turkey in mitigating the massive influx of refugees during last year. The visa-free travel deal is part of a larger strategic cooperation between the EU and Turkey to reduce the flow of migrants into Europe, since the migration of over 1.3 million people in 2015 alone.

The EU has tried to make the benefits of visa free travel contingent on revising the terror policy, but is unable to apply enough pressure to Turkey because of Erdogan’s rhetorical legitimation of the terror policy, and the support the country has given the EU to stem and redirect the refugee flow.

The Turkish government insists the laws are necessary to counter the threat of Kurdish and Islamic State terrorism. Turkish minister to the EU Volkan Bozkır expressed that Turkey considers it impossible to “revise the legislation and practices on terrorism while our country continues its intense fight against several terrorist organizations.” This refusal was accompanied with accusations that the EU is indifferent to the threats Turkey faces, creating a counter-narrative to insulate the state from criticism.

EU officials challenge this position, pointing out the ways in which the terror policy is actually used, which has been extensively documented by human rights NGOs.

The degree to which these issues are linked is demonstrated by the fact that Turkey has not been hesitant to praise its role in the reduction of the migration flow into the dialogue. An Erdoğan adviser tweeted recently: “The European Parliament will discuss the report that will open Europe visa-free for Turkish citizens. If the wrong decision is taken, we will send the refugees back to Europe.” While a tweet doesn’t amount to official policy, it demonstrates that the assistance with migration flows and the pressure to rewrite terror policy are not mutually exclusive issue areas. In addition, the Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, who largely brokered the migration deal on Turkey’s behalf, recently departed from his position. This changes nothing for EU officials who insist agreements are negotiated with governments, not individuals, but behind the public diplomacy is the reality that Turkey’s next prime minister will be recruited in Erdoğan’s image, an image that has pushed Turkey and the EU apart.

The EU’s reliance on Turkish assistance in mitigating migration flow, coupled with Turkey’s ability to point to its involvement in NATO operations against ISIS insulates Turkey on the issue of its terror policy from multiple angles. This makes it unlikely that the EU or NATO will be able affect Turkey’s current terror policy, despite the fact that this very policy is used to repress civilians and to undermine NATO efforts against ISIS. Turkey maintains its strategic importance for Europe and for NATO, and while NATO can can refuse to support antagonistic moves by Turkey, it cannot easily abandon its collective security mandate. The increasing threats from the PKK, ISIS and Russia, keep the possibility of escalation as a central concern, despite NATO’s desire to avoid it.

Turkey is at the centre of these overlapping security concerns for Europe and for NATO and seems to exacerbate issues and challenges that are never wholly separate from each other. Turkey represents Europe and NATO’s most complicated puzzle, and the result is that the NATO-Turkey-EU relationship remains in a state of ambiguity. This status quo is a consistent detriment to the NATO alliance, to the status of EU soft power and above all to Kurdish peoples and Turkish citizens.

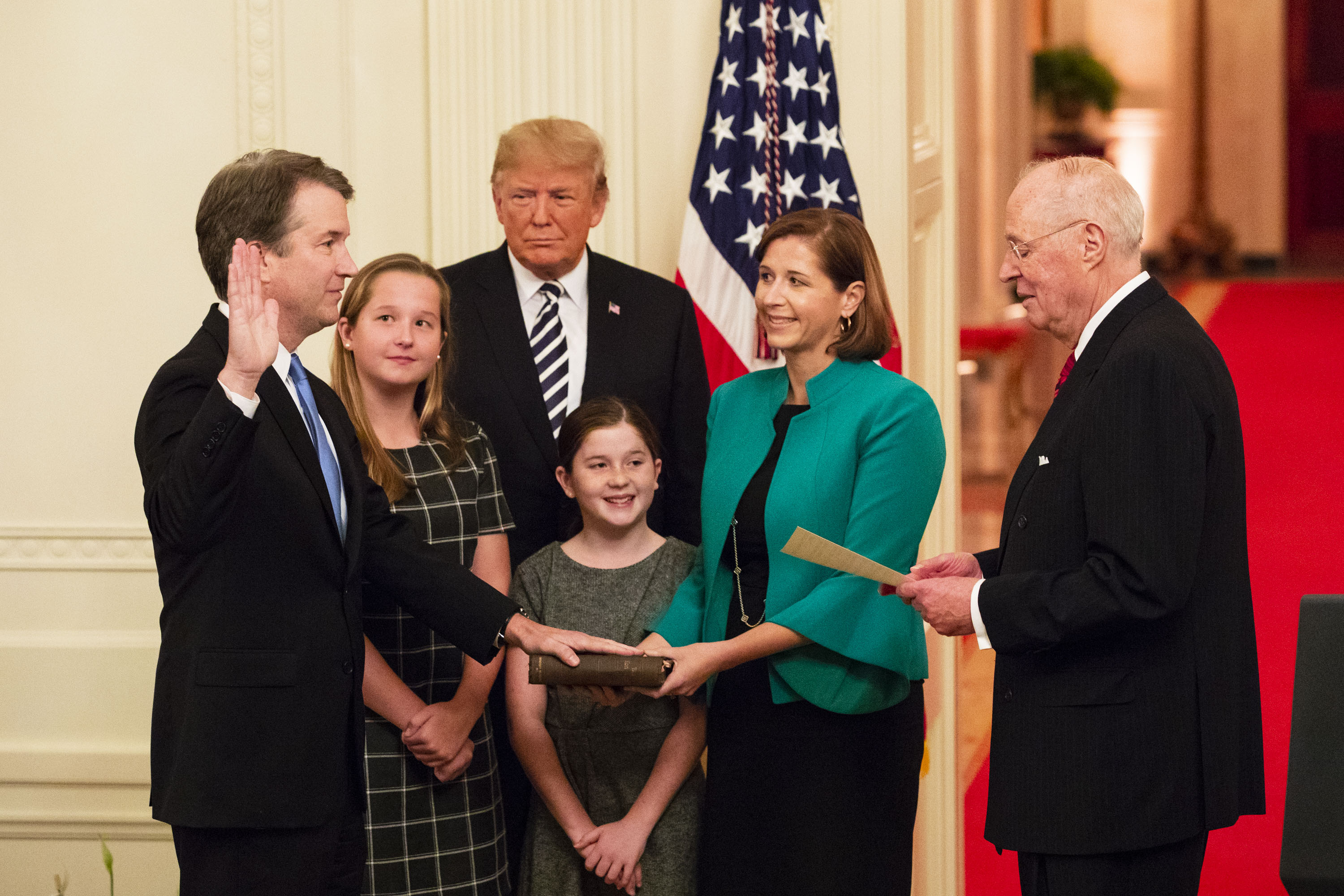

Photo: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan via Flickr. Public Domain.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.