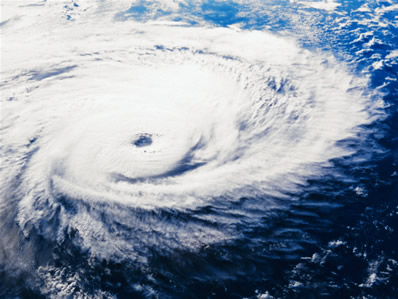

The potential consequences of global climate change have attracted the attention of policymakers and commentators for many years. The public has become familiar with – though hopefully not inured to – predictions of rising sea levels, natural disasters, and humanitarian crises. To some extent, these alarming discussions revolving around climate science and emergency planning have overshadowed efforts to examine the security implications of climate change. In 2009, Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen wrote about NATO’s interest in climate change and the need for a coordinated response from the security community. Almost four years later, there has been frustratingly little progress, but the issue remains a pressing one. As the North American media concentrates on the dangerous heat in the US Southwest and the recent flooding in Alberta, it seems appropriate to re-examine this issue and assess how NATO should engage with the global warming.

[captionpix align=”right” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/climate-change-2.jpg” captiontext=””]

If the dire predictions of climate scientists are realized, we can expect a significant rise in conflict owing to resource scarcity and population displacement. Economically impoverished areas will likely be disproportionately affected. Global warming is also impacting the geography of the Arctic region, which has prompted a great deal of interest and concern from several NATO members. This presents a stark challenge for those tasked with pursuing national or global security. However, the fact that these challenges are the result of climate change does not necessarily mean that the response to them should differ from the reaction to other security concerns. Essentially, climate change is quite clearly a security issue, but aside from addressing its consequences using already established political and military practices, the role for security organizations like NATO remains unclear.

The climate issue is just one of several examples of NATO’s endeavouring to establish its relevance on the 21st century security landscape. In recent years, international affairs have been defined not by international relations in the strictest sense, but by socio-environmental concerns. Protests, insurgencies, natural disasters, demographic shifts, and population displacement were pressing issues during the Cold War, but they tended to be shaped by the context of the political struggle between the Soviet Union and the United States. Since the Cold War, this situation has been reversed to some extent, with social circumstances establishing the context for international politics. This has led some critics to decry NATO as a hopelessly outdated institution created for Cold War politics and ill-equipped to confront the challenges of the 21st century.

While the attempts to dismiss NATO as irrelevant are overzealous, these criticisms cannot be ignored, and when it comes to climate change they may have some validity. Climate change is a global social concern that a political-military alliance may be ill-equipped to address. Innovation and adaptation is not an impossible task for NATO, but the Alliance is fundamentally an international, political, and military one. Climate change is a global concern, and although it does impact relations between states, a distinction must be made between global issues that transcend borders and international matters that tend to reinforce them. Of course, global and international phenomena interact and are not dichotomous, but one can be distinguished from the other. The political-military concerns that NATO was established to address tend to revolve around territorial sovereignty and security within the borders of individual states. Climate change, as a global issue, demands a transnational response that NATO has no mandate to provide on its own.

This is not to say that NATO has no role in the emerging challenges of the 21st century. It is important to note that the challenges of the 20th century have not disappeared. Military operations still require coordination, as evidenced by the recent Libya intervention, and NATO will likely continue its traditional military role. As for emerging issues, the digitization of security has taken on increasing importance in recent years, and although this issue could be described as a global one, the recently publicized instances of espionage indicate that cyber-security remains a largely international concern.

From an institutional perspective, it is understandable that NATO would try to assert its relevance to climate change. Institutions often try to maximize their mandate in order to increase their influence and prestige, but also because they hold genuine confidence that they are suited to the task in question. Beyond this general tendency, it is true that NATO will likely have to grapple with the security consequences of climate change, so no one can begrudge the organization’s leaders for discussing the issue. However, despite the fact that NATO will be impacted, it remains to be seen whether it will be able to satisfy those who want it to assume an effective leadership role in the effort to curtail and adapt to global warming.